Bookshelf: Local poets, civil rights books are recommended reading in April

I have to admit that I rarely read poetry. I know it is a great failing for someone who spends so much of her work life and leisure time immersed in books. But the fact is, I don’t know a cinquain from a sonnet without Googling it. And don’t even get me started on a villanelle.

That’s why I’m grateful April is National Poetry Month. It prompted me to broaden my horizons and read some poetry for a change. The experience reminded me that knowledge of poetry’s various forms ― haiku, free verse, rondeau, sestina (honestly, there’s no end to them!) ― is not a requirement for enjoying poetry.

For my National Poetry Month reading, I chose two books recently named to the 2021 list of Books All Georgians Should Read, selected by the folks at Georgia Center for the Book.

In a bit of serendipitous timing, Atlanta resident Julie E. Bloemeke’s “Slide to Unlock” ($18, Sibling Rivalry Press) is perfectly suited for the pandemic. Containing poems written over the course of 10 years, it explores what it means to connect with others in the age of digital communication. In sections titled “Dialing In,” “Call Waiting,” “On the Line” and “Cellular,” Bloemeke’s poems center on various permutations of intimacy from teenage desire to encounters with ex-lovers to the comforts of marriage to a partner who keeps his word.

Georgia State University professor Beth Gylys’ “Body Braille” (Iris Press, $16) is organized around the five senses and explores a wide range of topics from date rape to world hunger. “A Friendship” and “Riding Lessons” examine bittersweet memories of childhood friendships. “Backwash” is an anguished meditation on mourning that underscores the knowledge that we can never completely know a person, even those with whom we are intimate.

In reading these two books, it struck me that poetry is like literary alchemy. Poets are able to evoke such deep emotional responses with so few words. That is a special kind of gift worth recognizing not just during National Poetry Month, but all year long.

Both Bloemeke and Gylys are nominated for the Georgia Author of the Year Award. Winners will be announced June 12 on Facebook Live at facebook.com/GeorgiaWritersAssociation.

For those who prefer their poetry read aloud, The Academy of American Poets presents a free, virtual gala starting at 7:30 p.m. April 29. Chaired by Meryl Streep, the event will feature poetry readings presented by poet Richard Blanco, actress/director Regina King, singer/songwriter Lucinda Williams, actor/singer Lauren Ambrose and YA author Jason Reynolds, among others. To register, go to poets.org/gala/2021.

***

On a separate topic, this month marks the publication of two highly anticipated books about civil rights.

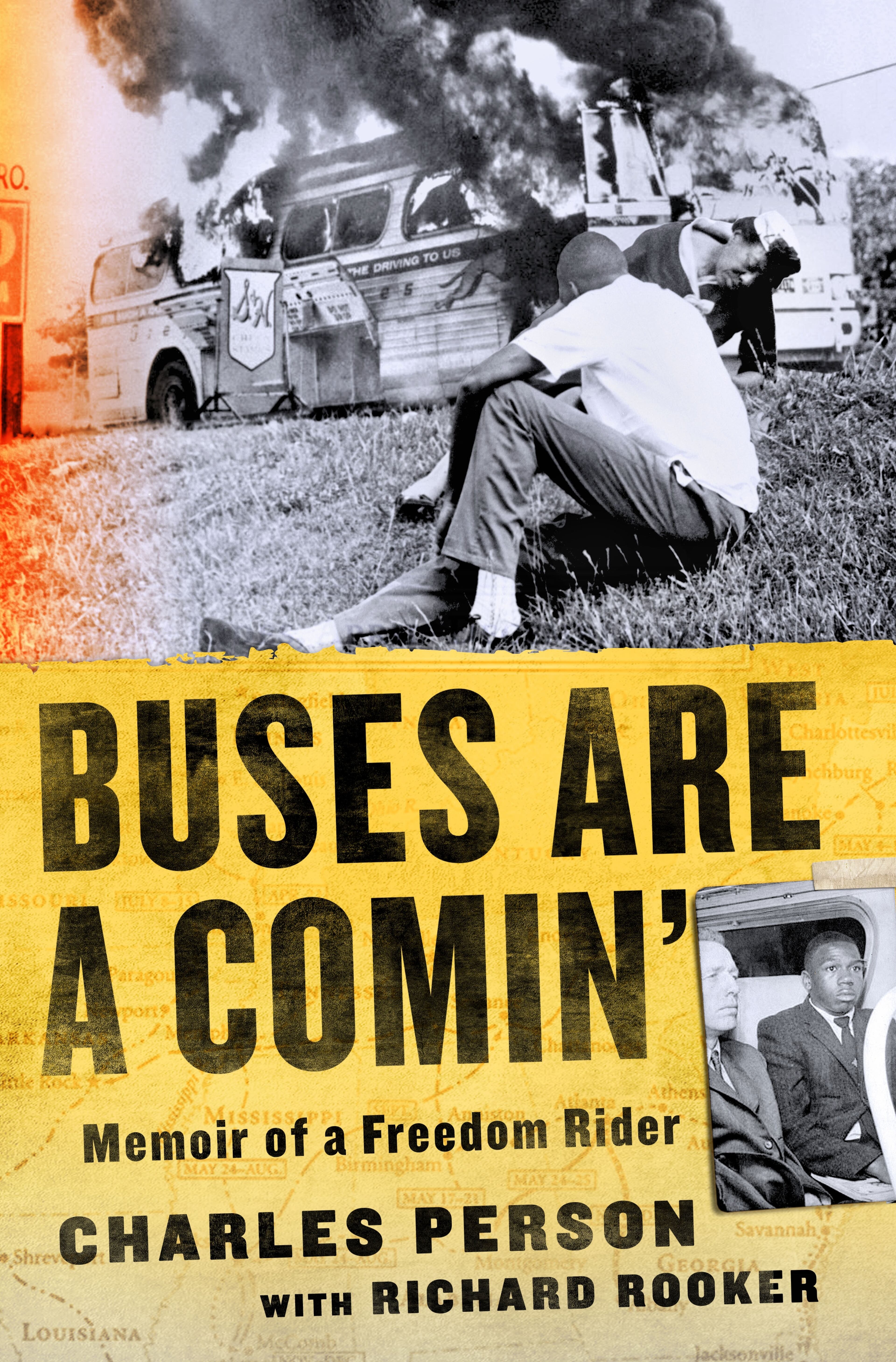

“Buses Are a Comin’” (St. Martin’s Press, $26.99) is a memoir by Atlanta resident Charles Person about his experience as the youngest Freedom Rider. Joining civil rights leaders John Lewis and C.T. Vivian, among others, Person was just 18 in 1961 when he boarded the bus in Washington, D.C., to test the Supreme Court ruling that it was unconstitutional to segregate interstate buses, waiting room terminals, restrooms and restaurants.

Written in collaboration with Richard Rooker, “Buses Are a Comin’” chronicles Person’s political coming of age during the civil rights movement. As a Morehouse freshman, he witnessed Martin Luther King Jr.’s lunch counter protest at Rich’s in 1960. Person was frustrated that organizers had restricted active participation to just upperclassmen, but it whet his appetite to get involved. Seven months later, he joined the Freedom Riders and put his peaceful protest training into practice when he was beaten by a mob of segregationists in Birmingham, Alabama. Person’s memoir is a sobering, first-person account of that historic bus ride.

And in a major literary event, a never-before-seen novel by Richard Wright has been published. “The Man Who Lived Underground” (Library of America, $22.95) is a harrowing account of an innocent Black man who police frame for committing a double murder. While his wife gives birth to their child, the man is beaten and tortured until he signs a false confession. Then, in an act of desperation, he escapes into the city sewer system.

The book contains graphic portrayals of police brutality that were deleted when the story was originally published as a short story in 1944. Now, for the first time, Library of America is publishing it intact as Wright intended. It follows Library of America’s unexpurgated publication of Wright’s novel “Native Son” and memoir “Black Boy,” after it was discovered that parts of those books had been censored when originally published.

Just 154 pages long, “The Man Who Lived Underground” is accompanied by Wright’s essay “Memories of My Grandmother” and an afterword by the author’s grandson, Malcolm Wright.

Suzanne Van Atten is a book critic and contributing editor for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. svanatten@ajc.com