“The Say So” by Atlanta author Julia Franks is a powerful work of historical fiction that examines the lifelong impact of adoption through the generations. Opening in 1959 and exploring forced adoption before delving into adoption by choice in the post-Roe v. Wade ‘80s, Franks’ probing narrative uses tenderness and nuance to ask the complex, provocative and timely question: Who has the “say so” over a baby’s fate?

A perfect storm emerged in post-Depression America. In the author’s note, Franks writes that the unwed pregnancy rate “doubled and tripled” between 1940 and 1964. The post-war middle-class was booming, and by pairing children born outside wedlock with married couples struggling to start or expand their families, the parents of affluent girls who had gotten “in trouble” could shield their daughters from social ruin. According to Gabrielle Glaser, author of “American Baby: A Mother, a Child, and a Shadow History of Adoption,” more than 3 million single women were coerced into surrendering their children between the end of World War II and the passing of Roe v. Wade in 1973.

In 1959, when Edie Carrigan “gets herself” pregnant at the promising age of 17, tight constraints rule the prevailing social order. She’s in love with her boyfriend Simon Bloom and, although he’s Jewish, she’s Catholic and he’s headed to medical school while she’s still in high school, they believe they can build a life together. Instead, their parents send Edie to a maternity home where she’s expected to ride out her pregnancy in secret and relinquish her child for adoption.

Edie’s best friend Lucille “Luce” Waddell encourages Edie to comply and resume her path to college. Luce knows firsthand how cruel public ostracization is following a ruined reputation. After her parents got divorced, the girls at Central High School in their undisclosed North Carolina town ask her to leave their circle because they “believe in family.”

The friendship between Edie and Luce takes center stage as the teenagers, opposites in many ways and set apart from the rest, develop an appreciation for each other’s differences. Edie admires Luce’s focus on the greater world; she’s one of the few people in their orbit paying attention to the emerging civil rights movement. Luce possesses a determination Edie describes as “an ambition that gaped so large it felt as if it opened something inside me, too.”

Luce is equally captivated by Edie. She’s not only beautiful but willing to see the world through a lens of truthfulness her parents would prefer she ignore. Franks paints a vivid portrait of the 1960s social structure. Girls are expected to be pretty and nice, chaste and acquiescent. College is for meeting a husband, a degree preparation for homemaking. Edie plays the role she’s been assigned until her heart gets in the way. She doesn’t understand why a difference in religion or age should separate her from Simon. And she’s devastated by the futility of her reality when, as a reward for relinquishing her child, her mother grants her permission to wear a pencil skirt.

Weaving between Edie’s and Luce’s perspectives, Franks reveals how these distinctive characters push against different female constraints. Luce cannot fathom trying to “trick” a boy into believing she’s either nice or pretty. She sets her sights on college and independence, determined to rise above the poverty her divorced mother can’t escape and make a difference.

Edie floats through the world on a cloud of her own privilege, refusing to accept she cannot marry Simon and keep her baby. She exists in a state of denial that’s fascinating to observe as she psychologically severs herself from reality while enduring tactics used to break down unmarried women who resisted adoption in the 1960s. A psychiatrist tells Edie that unmarried pregnancy is her “rebellion against being a woman” and cites Sigmund Freud’s castration complex. Her priest declares her baby “ill-gotten gains”; the social worker insists if she loves her child, she would gladly secure it a better life.

The time Edie spends in the maternity home introduces her to a variety of girls in differing situations who share one common truth: There is no place in society for an unmarried mother. Nothing drives this home harder than Sally, a 45-year-old college professor who is being forced to give up her second baby or face being fired and left destitute with “no referrals. No pension. No place for me to go.” Edie’s maternity home experience is both humbling and empowering, until she makes a series of choices that seal her fate.

Flashing forward to 1984, part two focuses on Meera Scott, a graduate student in her early 20s living in Virginia facing unplanned pregnancy. Meera recently broke up with her boyfriend, is pro-choice, not religious and happens to be Luce’s daughter. She decides on adoption over abortion, against her successful mother’s advice, and faces an outcome that is far more tragic than she imagined possible.

It’s through Edie and Luce’s friendship that the storylines intertwine, and Edie and Meera find healing in their shared maternal grief. In “The Say So” Franks has, simply put, spun together a gorgeous and tremulous story exploring multiple perils of unwed pregnancy that is wildly applicable today.

By the time Franks gets to the final author’s note stating that “women who choose adoption are not so different from women who seek abortion rights,” her tender narrative has already shouted from the rooftops that all women are “fighting for the same thing, the say-so over their own decisions and bodies.” And her message is delivered with profound delicacy and heart-wrenching grace.

FICTION

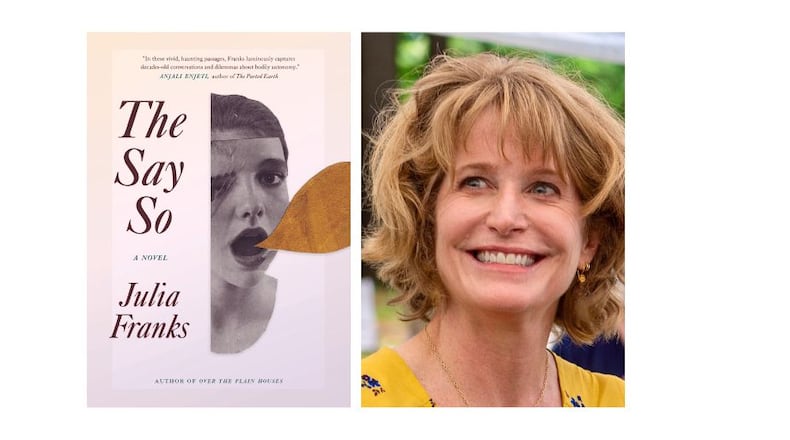

“The Say So”

by Julia Franks

Hub City Press

368 pages, $28

AUTHOR EVENTS

Julia Franks. In conversation with Trudy Nan Boyce. 7 p.m., June 6. Free. Decatur Library Auditorium, 215 Sycamore St., Decatur. 404-370-3070, www.georgiacenterforthebook.org

Also, in conversation with Jessica Handler. 3 p.m., June 11. Free. A Cappella Books, 208 Haralson Ave., NE, Atlanta. 404-681-5128, www.acappellabooks.com

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured