This story was originally published by ArtsATL

Following the “unexpected” death of his father, De’Shawn Charles Winslow tried to unravel the mystery of a man who was both a loving presence and an enigma in the life to his 29-year-old son. “He was a quiet man who’d had a colorful past: a criminal background, multiple failed marriages,” says the Atlanta-based author. “When he died, I became curious about his youth, his young adulthood. So I turned to writing to make up the answers I couldn’t get.”

Winslow dropped the project as his grief subsided. But his desire to understand people and their motivations led to his career as a writer.

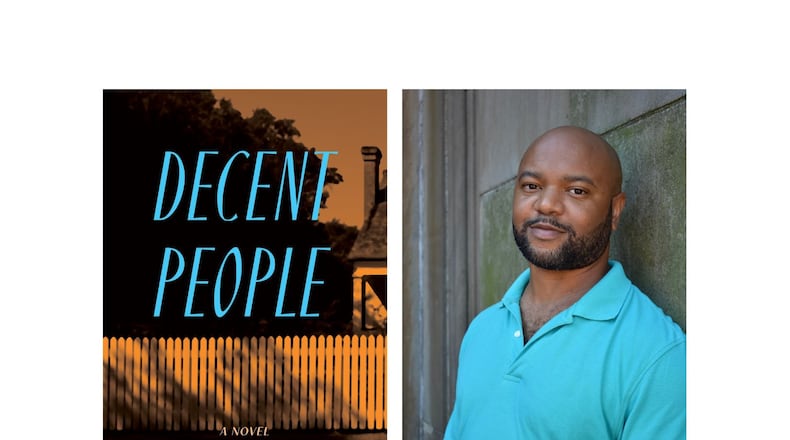

A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Winslow — who was born and raised in Elizabeth City, North Carolina — published his debut novel, “In West Mills” (Bloomsbury Publishing, 272 pages), a Center for Fiction First Novel Prize-winner, in 2019. Fans of the novel will recognize the fictitious setting of his sophomore effort, “Decent People” (272 pages, Bloomsbury), which is already garnering critical acclaim for using a whodunit to peer underneath the social dynamics of the South.

The story opens in 1976, when Josephine “Jo” Wright returns to her hometown of West Mills, North Carolina, from New York City to marry her childhood sweetheart, Olympus “Lymp” Seymore. When Lymp emerges as a primary suspect in the shooting deaths of his three half-siblings, Jo’s focus shifts from planning her wedding to trying to prove her fiancé's innocence. But as Jo looks beneath the town’s veneer of Southern charm and gentility, she’s forced to reckon with an underside that’s rife with classism, homophobia and inept policing.

Winslow — who teaches writing in programs at various City University of New York colleges and Pacific University in Stockton, California — shared his thoughts with ArtsATL on overcoming self-doubt as a writer, the conundrum of decent people behaving badly and how he was nearly stumped by one of his characters.

Q: In a recent Instagram post, you stated, “I can’t believe I wrote a second book.” What kind of negative self-talk did you have to ignore to stay the course as a writer?

A: I was a slow learner as a child. My reading was quite labored. I’m still shocked to have written one book. I’m equally surprised to have stuck with writing long enough to have written a second one. Sometimes the little invisible Donnie Downer on my shoulder says, “You’re slow. What are you doing reading and writing novels?” Donnie gets really loud sometimes, but I’m getting better at ignoring him (laughs).

Q: As the story opens in 1976, West Mills is still segregated. How does this social dynamic shape your characters and the narrative arc? What were the thorniest aspects of imagining life in the South nearly 50 years ago?

A: I think a thorny aspect was realizing that even in the late ‘80s, the town’s racist culture was still alive and well. A man in the community, whose nickname was Breeze, an uncle-like figure for me, was brutally beaten. I remember overhearing the adults speak about the incident, who had done it, and why. For my Black characters, knowing that at any moment they could be harassed (or worse), unprovoked, certainly determines how they interact with the white people in town. While most of the Black people in West Mills aren’t victims of physical hate crimes, they know that white supremacy could harm them in other ways: their livelihood, for example. But these characters (all of them), at the end of the day, are willing to fight to protect their family and status. That willingness translated to bad behavior, which, I feel, is necessary in fiction.

Q: The story revolves around a triple homicide. Did you know who the killer was at the outset, or did they reveal themself to you over time? Was there an alternate ending?

A: I didn’t know who the killer was right away, and that slowed me down quite a bit. There was once another couple in the novel who were involved with the Harmons, and at one point I wanted one of them to be the killer. But I later decided to save that couple for another book. When I later had the thought of who the actual killer should be, it shocked me — so much so that I almost changed my mind again!

Q: Your book title belies the fundamentally indecent behavior of many characters — all of whom are victims of racism; some of whom are perpetrators of homophobia, professional malpractice and vicious gossip; and one of whom is a cold-blooded killer. What was your thinking behind the title?

A: For me, the title conveys the idea of people doing bad things, but (for some of them) with good intentions. All of the characters in this book are victims of patriarchy, and patriarchy can make people do some crazy things in the name of religion and tradition. I, in no way, mean to excuse racism, sexism, violence, plain ol’ hate, etc. But I know that patriarchy is often at the root.

Q: You earned an MFA at Iowa Writers’ Workshop. How did the experience change you as a writer?

A: I knew what types of stories I wanted to write before I applied to any MFA program. Getting an MFA provided me with community who shared that same joy for putting our feelings, observations and curiosities on the page. And people who will read your work and tell you what you do well and where you need more practice. One can get that among any group of caring writers and readers.

Q: You cite Zora Neale Hurston’s “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” Alice Walker’s “The Color Purple” and Toni Morrison’s “Sula” as major influences on your writing. What aspect of their storytelling resonate with you most powerfully? How are their examples manifest in the telling of “Decent People”?

A: I love Hurston’s work because she was not afraid to show readers who her characters were, right down to their dialect. I admire almost everything about Morrison’s body of work, but I particularly love how very memorable her characters and their predicaments are. Who can forget a woman with no navel, or a white man nicknamed “Tar Baby”?

Q: There is a preponderance of female voices throughout the novel. Did you have any reservations about writing from a woman’s perspective?

A: When I wrote “In West Mills,” I feared there might be public resistance to me writing a central character that was a woman. But I know who I am and who raised me and with whom I spent my childhood. If I hadn’t followed my instinct and wrote what felt true to me and my heart, I doubt I would have been published at all.

Gail O’Neill is an ArtsATL editor-at-large. She hosts and coproduces Collective Knowledge a conversational series that’s broadcast on THEA Network, and frequently moderates author talks for the Atlanta History Center.

Credit: ArtsATL

Credit: ArtsATL

MEET OUR PARTNER

ArtsATL (www.artsatl.org), is a nonprofit organization that plays a critical role in educating and informing audiences about metro Atlanta’s arts and culture. Founded in 2009, ArtsATL’s goal is to help build a sustainable arts community contributing to the economic and cultural health of the city.

If you have any questions about this partnership or others, please contact Senior Manager of Partnerships Nicole Williams at nicole.williams@ajc.com.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured