On the 25th anniversary of the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution presents a series of retrospectives produced by the University of Georgia’s Carmical Sports Media Institute. The Eyewitness to History interviews offer the view of someone who was at a top moment on the Summer Games.

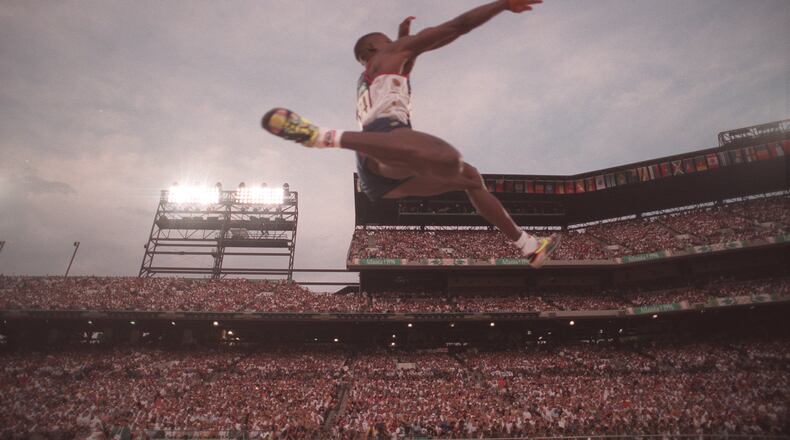

Carl Lewis and Mike Powell finished 1-2 in the long jump at both the 1988 and 1992 Olympics. At the 1996 Atlanta Summer Games, what was expected to be a clash of titans between two world-class athletes ended with one taking gold and making history and the other without a medal.

Lewis was the three-time defending Olympic champion in the event but, at 35, was not the favorite to win. Powell beat Lewis and set the long jump world record at the world championships in Tokyo in 1991 -- a record that stands today. Powell knew a gold medal in Atlanta would put him near the top of the pantheon of track and field athletes.

The best long jumper in the world at the time, Cuba’s Ivan Pedroso, came into the ’96 Olympics with a nagging injury. That seemed to leave Lewis and Powell to duel it out for the Olympic gold.

The crowd was eager to see the United States sweep the medals in the long jump, as U.S. athletes did at the previous two Olympics. But Powell only had eyes for gold. Here is his take.

“I was able to get the qualifying mark on my first jump, which is always the goal in the qualifying round, because you want to save energy for the final. And I had a little bit of soreness in my groin, so I was doing some extra stretching. ... It was in the back of my mind, but I was used to competing injured. You’d have, like, little nagging injuries. I wasn’t necessarily worried about it.

“I was just really just excited about the day (of the final). Just waiting for the time to go by so we can get started. That’s always the hardest part, just waking up and, more like a kid at Christmas, you wake up with, ‘Oh, man, OK, but I got to wait.’ ... It’s always hard because you have all these thoughts going through your head. If you’re in a good mindset and you’re confident, that is great, but if you have things that you’re worried about, then sometimes it hurts.”

Powell watched as Lewis narrowly made it into the final round, needing three jumps to make the automatic qualifying mark. Then, on his third jump of the final round, Lewis went 27 feet, 10¾ inches to move into first place.

“When he jumped and the mark came up I was surprised because he hadn’t been jumping well all summer and this was the best he had in over a year. Carl and I, we have a good relationship now. Then I guess you could say it was a relationship of respect. But still on my side, you know, he was the enemy.

“Right after he made that jump, I walked over to him. I said, ‘Where the hell did that come from?’ And he started laughing. He said, ‘Mike, you’re crazy.’ I said, ‘Man, I know, but what the hell?’ I was thinking about him doing that.

“It was disheartening because everybody was saying that the track was so fast. And to me, it felt really slow. Like the track in Tokyo and most of the tracks, the surface is hard, so you get a big response off the track. For certain tight runners, the way they run a track like the one they had in Atlanta was more advantageous, but not for me. So, I felt really slow. And you know, when you don’t feel fast, it’s not a good thing when you need to get speed. So I wasn’t feeling overly confident about trying to get big jumps, but I always felt like I would be able to pull one out.”

As Powell approached the board for what would be his final Olympic jump, emotions overcame him. He fouled on the jump and finished out of the medals. Lewis became only the second track and field athlete to win four consecutive Olympic gold medals in the same event, joining U.S. discus thrower Al Oerter.

“When you do well in the Games, in the Olympics, you want to get (your) picture on the cover of Sports Illustrated. But after my jump, my last jump that I had, I fell face first into the sand and sand was all over me and they were snapping a bunch of pictures. So, when the Olympic magazine came out after the Games, in the middle, there’s a two-page spread of me laying in the sand, holding my groin with sand all over my body and head.

“I’ve had people come to me and bring that picture to me, ask me to autograph it. I’m like, ‘No, I’m not far away. How about if I go into your life and find a horrible mistake you can sign? This is signing that.’

“So that’s the image that I have, because that’s what that encapsulated the pain that I felt both physically and emotionally. I mean, this is almost like therapy for me, getting it out, because I can’t evade the question. I have to deal with it. It kind of helps me just to talk about it. I don’t run away from the feelings that I had. But at the same time, though, it was tough.”

Ethan Strang completed this interview as a student at the University of Georgia’s Carmical Sports Media Institute.

Eyewitness to History: Athens (Georgia) sees history — minus the hedges

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured