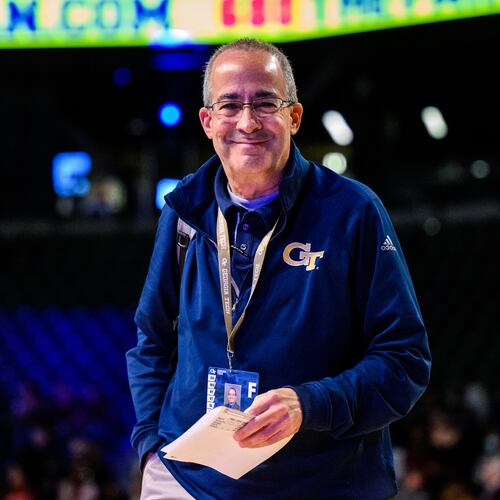

When Georgia Tech announced their dismissals in a news release Monday, school President Ángel Cabrera praised both athletic director Todd Stansbury and football coach Geoff Collins in statements for their efforts on behalf of the institute.

He noted Collins’ commitment to his players. He said of Stansbury that the Tech alumnus is and will always be an admired and respected member of the Tech community and that his dedication to Yellow Jackets athletes and love for Tech are admirable. It was because of the team’s poor on-field performance that they were being fired, Cabrera’s statement read.

Earlier that day, however, after he had met with both men in successive meetings to inform them of their terminations, their treatment did not express gratitude or respect. After being fired in his office, Stansbury and Collins were escorted to their cars to leave campus without being able to return to their offices and had to surrender their phones immediately, two people familiar with the situation told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

While their dismissals surely did not come as a surprise after weeks of speculation that their jobs were in danger for the underperformance of Collins’ football team, the manner in which they were handled after being dismissed surely did. It struck a nerve with others.

Tech great Bill Curry, who coached Stansbury and had had interactions with Collins, said that since he didn’t know personally that it had happened, he was assuming that such an action didn’t actually take place.

“But if it did, I would be utterly shocked and dismayed,” he said.

Asked for comment, an institute spokesman replied in an email that the school doesn’t comment on those sorts of details of personnel actions. During the tenure of former Tech President G.P. “Bud” Peterson (Cabrera’s immediate predecessor), such action was rare, according to a person familiar with Peterson’s policies.

It is not the norm within athletics. For instance, when Collins fired three assistant coaches at the end of last season, they were given all the time they needed to collect their belongings and were not monitored, according to the person with knowledge of Collins’ post-dismissal handling. The assistant coaches’ phones were not returned until January 2022, more than a month after they had been let go.

While in the relative past, former basketball coach Paul Hewitt (fired in 2011) and former football coach Chan Gailey (fired in 2007), both dismissed for performance reasons like Collins and Stansbury, were not walked out of the building or forced to turn over their phones, a person familiar with those events told the AJC. However, the same person said that he was “a little surprised, but not shocked” that it happened in that way Monday. He surmised that it was a protocol for the institute’s highest office, as people fired there often may have access to the school’s intellectual property or sensitive information.

Bob Vecchione, the CEO of the National Association of Collegiate Athletic Directors of Athletics, said in email that “this action does not strike me as unusual,” also theorizing that it probably was based on institute protocol.

Asked Friday if he had ever heard of such a processing, Vecchione responded, “In 30 years on the job, this is the first I have heard of any activity surrounding a dismissal.” He attributed the awareness of this instance to heightened coverage by media.

“I’ve never heard of that one before,” a Division I AD told the AJC. “That’s a new one for me.”

Tech graduate and major donor Steve Zelnak wrote in an email that he was not aware that the coach and AD were escorted to their cars, but that such a procedure is not an unusual practice in the corporate world.

When explained the circumstances with Collins and Stansbury, an expert in the human-resources field said that he also thought that the procedure might be part of institute protocol.

Peter Cappelli, director of the Center for Human Resources at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, wrote in an email that the practice of walking out fired employees and not letting them return to their workplaces typically is done to limit the risk of those former employees causing a disturbance or damage. But choosing that procedure also carries a different kind of risk.

“But the people who are watching think, ‘Wow, something really bad must be going on around here for the organization to do this. I wonder how widespread it was,’” Cappelli wrote. “You should also care about what these ex-leaders are going to say about the place if people ask them, and they will ask after this.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured