Homer Rice’s 17-year tenure as Georgia Tech athletic director requires no puffery. Between 1980 and 1997, he hired the school’s basketball and baseball coaches (Bobby Cremins and Danny Hall, respectively) with the most wins in school history and a football coach who won a national championship (Bobby Ross).

Rice’s personnel acumen was not limited to Tech. Perhaps his most impactful job placement was his hand in elevating John Swofford into the seat of ACC commissioner in 1997. Under Swofford’s leadership, the ACC was stabilized in an uncertain time, and its lofty place in college athletics secured for years to come. Swofford announced Thursday that the coming athletic year, his 24th as commissioner, will be his last.

“He was able to provide the leadership of all those schools and pull them together, and it became a very strong conference,” Rice told the AJC on Thursday. “I know he had a great record in national championships. He’s provided the leadership, and he does it without force. He has a way about him that he can persuade people, and they probably don’t even know they’ve been persuaded. He has that knack to do those type of things.”

On his watch, which followed a 17-year run as North Carolina AD, Swofford held league members together through an era of conference realignment, led unprecedented expansion of its membership and footprint and was a partner with ESPN in the development of the ACC Network, an arrangement that stands to improve the conference’s financial standing against its power-conference competitors.

“It has been a privilege to be a part of the ACC for over five decades and my respect and appreciation for those associated with the league throughout its history is immeasurable,” Swofford said in a statement. “Having been an ACC student-athlete, athletics director and commissioner has been an absolute honor.”

It might not have happened without Rice’s guidance. When Swofford was a UNC football player (graduating in 1971) and Rice the school’s AD, Swofford told Rice he wanted to someday have his job and asked how he could go about it. Rice encouraged him to earn a master’s degree in athletic administration at Ohio University, which Swofford did. When he graduated, Swofford recommended him to Virginia AD Gene Corrigan, who hired him.

In 1997, when Corrigan was retiring as ACC commissioner and Swofford was AD at North Carolina, Rice said he told Swofford, “John, that’s what you need to do.” Rice was on the nine-member committee that recommended his hire to the league’s presidents.

“And he’s been there ever since, until (Thursday), I guess,” Rice said.

When Swofford ascended to the job in 1997, the nine-school ACC was contained in six contiguous Southeast states. It was, above all, a basketball league. Recognizing the growing importance of football and the television revenue derived from it, Swofford led the conference to expand.

In 2003, the league attempted a messy and public raid of the Big East, one that prompted a lawsuit by five Big East schools against the ACC for a “deliberate scheme to destroy the Big East.” It resulted in the ACC’s addition of Miami and Virginia Tech that June, followed by Boston College in October, the latter deemed necessary to grow to 12 teams and be eligible to play a conference championship game in football.

“I think we haven’t distinguished ourselves in doing this,” Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski said at the time of the additions of Virginia Tech and Miami.

The ACC and the Big East plaintiffs settled their lawsuit in 2005. In 2011, the ACC took Syracuse and Pittsburgh to raise the league’s count to 14 teams. In 2012, the league completed its conquest of the Big East by adding Notre Dame for all sports but football and ice hockey – while securing an agreement that the Fighting Irish football team would play an average of five ACC opponents annually, adding more heft to the conference’s television package – and then bringing in Louisville after Maryland, an ACC charter member, bolted for the Big Ten. At its present 15 teams, the league has almost as many former Big East schools – seven – as it does ACC schools when Swofford became commissioner (eight).

At a time when conference realignment was raging and the viability of the ACC seemed uncertain, Swofford secured the league’s future in 2013 by convincing the league’s 15 presidents to sign a grant of media rights through the 2026-27 academic year (since extended through 2035-36), making defection all but impossible.

The expansion gave the ACC the largest geographical footprint and population among the five power conferences, leading to what may be Swofford’s final signature act. The creation of the ACC Network, the ESPN-owned channel launched in September 2019, has delivered a needed increase in TV money to the league’s schools to compete against its power-conference foes.

“(The ACC Network) only came about because of our expansion,” Swofford told the News & Observer of Raleigh, N.C., on Thursday. “That was very necessary in order to keep the league as one of the country’s most prominent ones during a very challenging change in the landscape of college athletics.”

An expanded ACC has had its costs. The round-robin basketball schedule, once a conference staple that added fire to the league’s rivalries, is but a memory. With the conference sticking to an eight-game league schedule and a two-division format for football, cross-division opponents (aside from the permanent partner, such as Georgia Tech and Clemson) play each other once every six years.

Particularly at a time when athletic departments are cutting budgets, the wisdom of playing in a league in which many opponents can be reached only by plane is up for debate.

For a league that puffs out its chest over its schools’ academic credentials, scheduling 9 p.m. midweek basketball games between cross-sectional opponents to provide ESPN with content seems to heavily prioritize only one half of the league’s mission statement, “to maximize the educational and athletic opportunities that shape our leaders of tomorrow.”

That said, it’s conceivable that, without Swofford acting in the league’s best interests to add to its numbers, the ACC could have been drastically diminished and seen member schools poached by the SEC, Big Ten or Big 12.

Chances are, with smaller schools and fan bases, the ACC will never catch the SEC or Big Ten from a financial standpoint. For example, in 2018-19, SEC schools received $44.6 million from their conference office. Tech’s expected take from the ACC in the coming fiscal year, the second year of the ACC Network, is $32.5 million.

Still, Clemson has emerged as a dominant player in football. ACC men’s basketball teams have won three of the past five national championships. And, much to the ACC’s delight, the league has more schools (seven, including Tech) in the top 50 of U.S. News & World Report’s best national universities than any other power conference.

How the ACC proceeds following Swofford is unclear. Fans who have bristled at the league being guided by a North Carolina alumnus might appreciate new leadership without any perceived allegiances. The Big Ten’s June 2019 hire of Kevin Warren, a Pennsylvania grad who came from the front office of the Minnesota Vikings (and is also the first Black person to lead a power conference), is such an example.

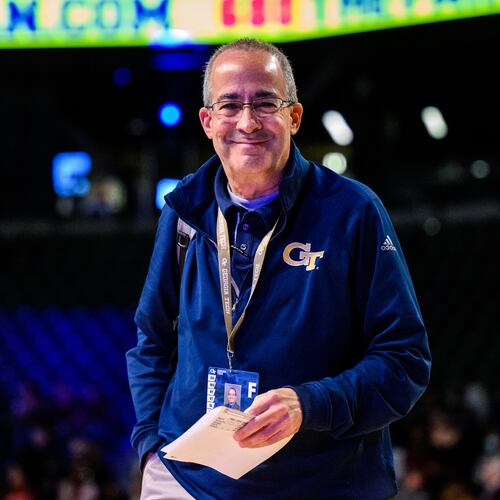

Swofford exits with the good wishes of many, including Tech AD Todd Stansbury, another Homer Rice disciple.

“Throughout his 23 years as commissioner of the ACC, John has advanced the values championed by Homer Rice, lifting the league, its member schools and its student-athletes to unprecedented heights athletically, academically and socially,” he said in a statement. “I am proud to share such tight bonds with John, and it has been an honor and a privilege to work with and learn from such an iconic figure in intercollegiate athletics. I wish him and his wife, Nora, nothing but the very best in retirement.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured