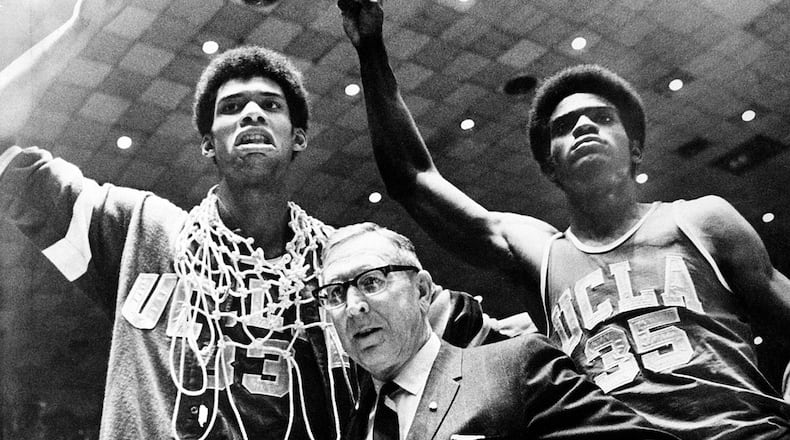

The record books tell only so much of the story of UCLA and legendary coach John Wooden. The stretch of 10 national championships in 12 years is almost mythical at this point, especially considering how treacherous the expanded NCAA tournament field is now.

The Wizard of Westwood died in 2010 at age 99, but there is still a way to pinch somebody and know it’s all true. That starts with reaching out to a man such as Larry Farmer.

The 61-year-old former Bruin, who was 89-1 in three seasons at UCLA while winning three national titles, is now director of player development at N.C. State. That’s his official title, but unofficially? A quick look around his office at the Dail Center tells you Farmer is a bearer of the Wooden legacy.

Seated at his desk, he can point to his right at a framed photo on the wall of UCLA’s 1972 national championship team. It was taken Oct. 14 his junior season, on photo day, like clockwork. The day before had been their team meeting when Wooden would give the take-care-of-your-bodies speech, which always included a demonstration of how he wanted players to put on their socks and tie their high-tops.

“He would talk about the proper way to put on your socks so your feet don’t blister,” Farmer said. “And how to tie your shoes so you had extra support with your tape, so you’d get over a sprained ankle a lot quicker.”

Bob Knight had his man-to-man defense, Jim Boeheim the 2-3 zone. Mike Krzyzewski is known for his motivational skills, and for Wooden, it was his attention to detail.

Farmer points to the opposite wall of his office, where he has a framed photo from practice his senior season of him standing next to Wooden. Wooden was in his dark blue UCLA warm-up jacket, which Farmer can guarantee had a 3-by-5 index card in the pocket with notes outlining that day’s practice.

Farmer then opens his desk drawer and pulls out index cards of his own.

“A lot of people want to know if (Wooden) was exactly the way he was portrayed, which is always fun for anybody that played for him,” Farmer said. “It makes you very proud to say, ‘Yeah he was that, and he was more.’”

Farmer made index cards for every practice he’s coached for the past 40 years, including three as head coach at UCLA, head-coaching jobs at Loyola and Weber State, and assistant-coaching jobs at Western Michigan, Rhode Island, Hawaii and the NBA’s Golden State Warriors. Farmer also spent three years coaching a club team in Kuwait and five coaching Kuwait’s national team.

Farmer was 61-23 in three seasons as head coach at UCLA. But like Gene Bartow, Gary Cunningham and Larry Brown before him — all of whom he coached with as an assistant — Farmer found expectations too great. He resigned four days after UCLA granted him a three-year extension.

“Winning the national championship was something that was expected, but I didn’t see where I was going to be able to do that in the next year or two,” Farmer said. “I’d just recruited Reggie Miller, so it wasn’t that we didn’t have good players. But UCLA, as history has proven, has never been about just having good players or just fielding good teams or being competitive. That’s not what we created.”

It’s funny, looking back, that Curry Kirkpatrick wrote in a 1981 issue of Sports Illustrated: “Larry Farmer isn’t going anywhere.” He’s been around the world. But for a kid growing up in Denver on his father’s military income, whose first flight was for a recruiting visit to Kansas, Farmer dreamed of seeing places he read about in his encyclopedia.

“Everything that I saw in those books, because of basketball, I was able to see,” Farmer said. “I’ve been to the Eiffel Tower. I’ve been to the Colosseum in Rome. I’ve been to the Great Wall of China. I’ve seen them all.”

Everywhere he went, Farmer packed three-ring binders. In them are practice synopses he copied off index cards. He can look up how much time that good defensive UCLA team in 1975 spent on defense in practice.

Several contain pages of “Woodenisms,” sayings or poetry Wooden liked to recite, such as Abraham Lincoln quotes. One listed “26 Suggestions for Success.”

But there are plenty Farmer doesn’t have to look up to remember, like “Be on time when time’s involved” and “It’s amazing how much can be accomplished when no one is concerned over who gets the credit,” “Be quick, but don’t hurry” and “There’s nothing stronger than gentleness.”

Farmer said he didn’t always understand their meaning as a player, but the older he gets, the wiser Wooden becomes. Before he knew it, he was texting “Woodenisms” to his own son before his basketball games at Denison University.

It’s true, Wooden didn’t ever swear, Farmer said, which he knew from all his years with Wooden as his head coach, mentor and friend. But he was no pushover either, and he knew just how to reach each of his players. For Farmer, that meant appealing to his sense of leadership.

“There were times where it would have been easier for him to just have called you a name and gotten it over with,” Farmer said.

One of those times was Farmer’s senior season, when Wooden caught him skipping sociology class. Farmer was in the student union playing pool, hustling a little lunch money, as he says, when Wooden sent a team manager looking for him. Farmer asked the manager if Wooden had told him to go to Haines Hall, where his class was. The manager said Wooden told him to go to the student union first.

“I was so busted,” Farmer said.

He walked slowly to Wooden’s office, trying to make it look like he’d been walking back from his classroom building, which was farther away. It didn’t fool Wooden.

“Instead of yelling at me, he just looked at me and said ‘I’m very disappointed,’” Farmer said. “You’re team captain, and I expect you to be a leader. And this is how you lead?”

Those stories make Farmer smile now. It doesn’t take much to make him cry either. Farmer chokes up when he talks about taking his two kids to see Wooden in his Atlanta hotel room at the 2002 Final Four.

Wooden sat Farmer’s 7-year-old daughter Kendall on his lap and 13-year-old Larry by his side. He kidded that their father may talk a good game about his career, but he never could shoot. But Wooden didn’t talk basketball for long.

“He recited poetry,” Farmer said. “He talked about the importance of school and family. It was exactly the same conversation he had with me all those many years ago. Maybe the purest way of telling me how much he loved me was how he treated them.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured