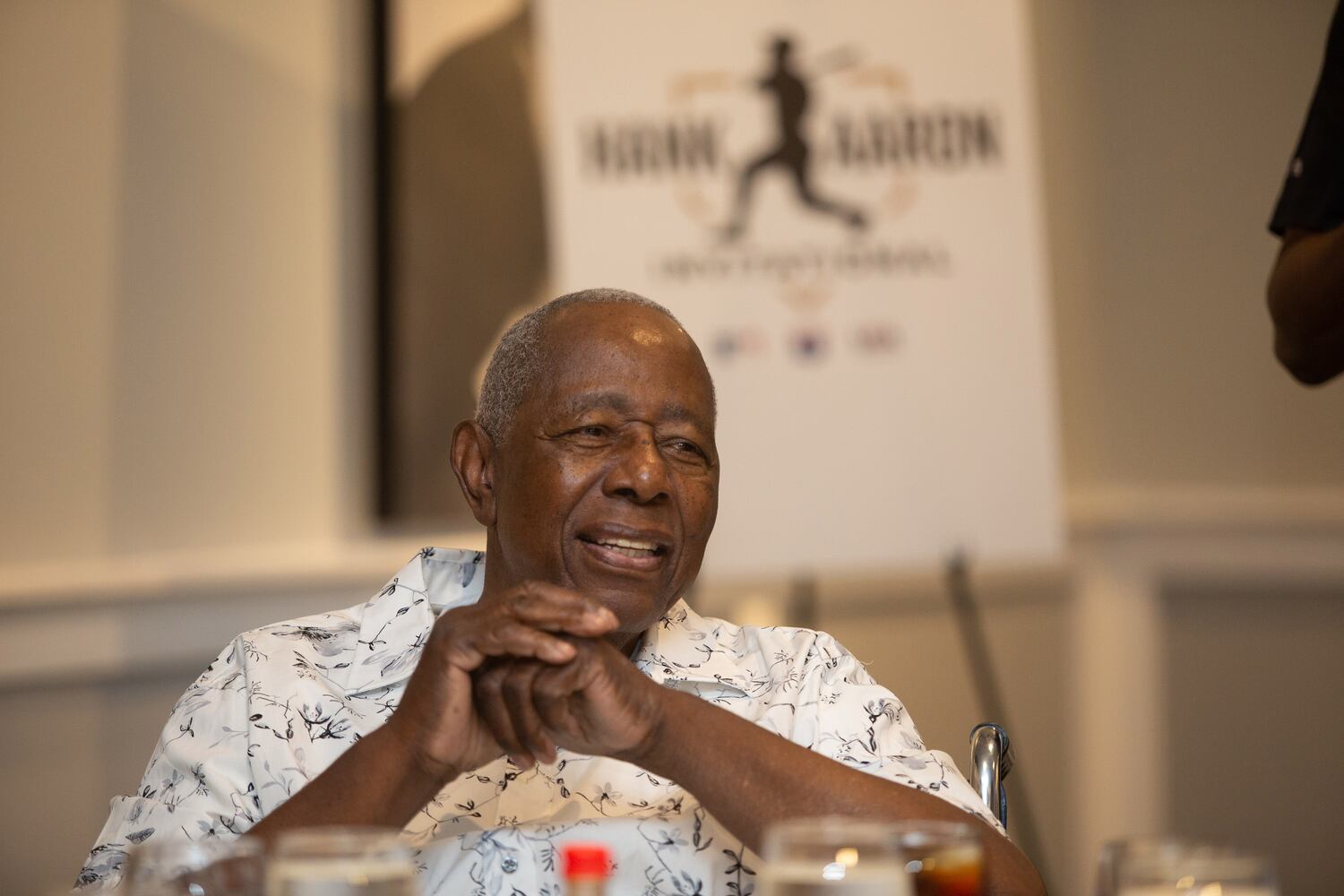

Hank Aaron, a member of baseball’s Hall of Fame and known by many as the Braves legend who hit 755 career home runs, was brought into the ballroom of Paschal’s restaurant Friday and instantly met by a crowd of young baseball players eager to get a view of him.

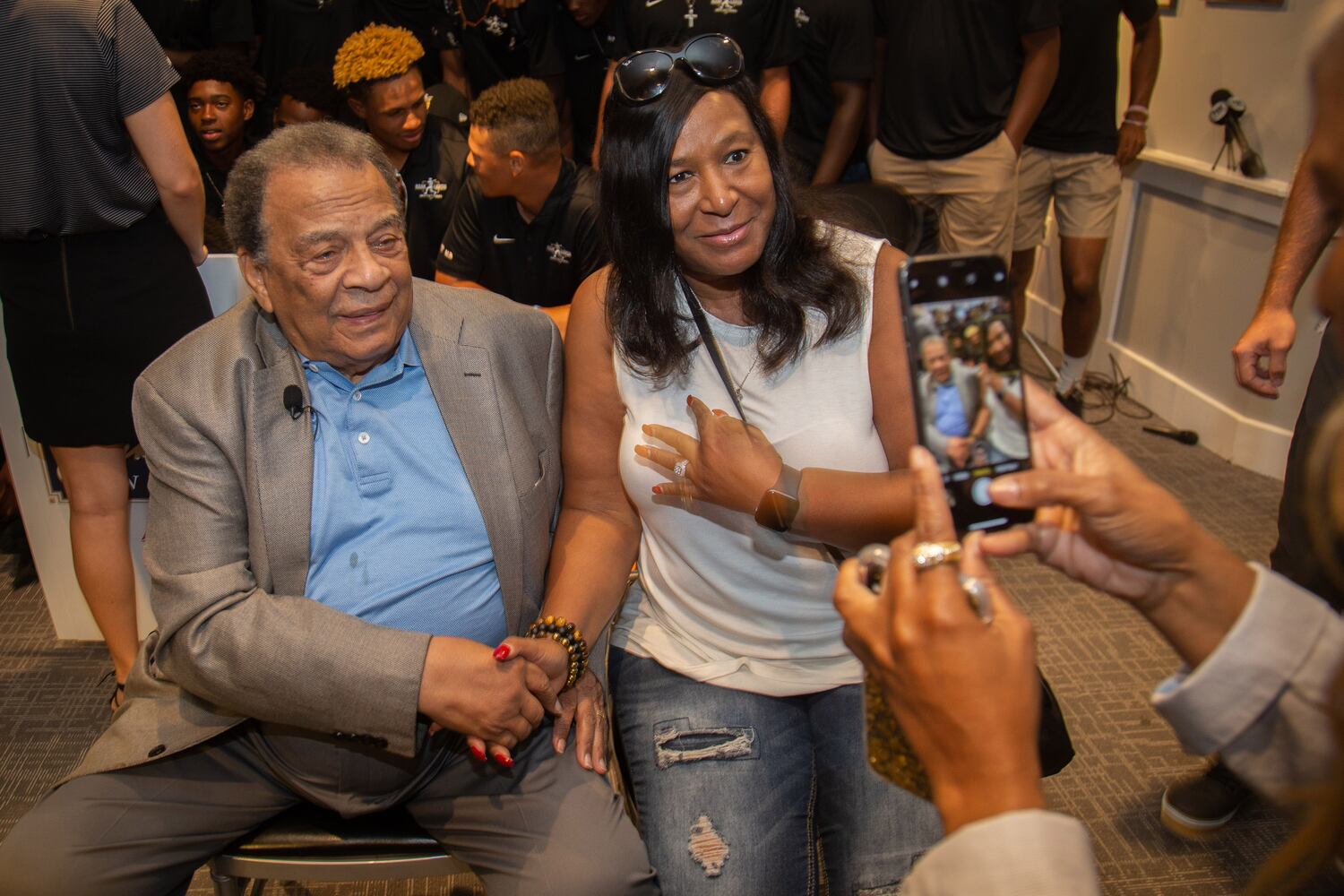

Last month, the fifth annual Hank Aaron Invitational, an on-field diversity initiative designed to get youth baseball players to the next level, selected 44 of its top players to receive a civil-rights tour around Atlanta, concluding the week with a showcase game at SunTrust Park on Saturday. On Friday, the players got to have lunch with Aaron and former United Nations Ambassador and civil-rights leader Andrew Young. In many ways, the time spent was just as special for Aaron as it was for each athlete.

“It fills my heart, it makes me feel very proud,” Aaron said. “(Proud) of the fact that 23 years you played the game and small things like this happen. You’re in a room and you’ve got so many of these “kids” with your namesake, hoping one day that they too will play baseball.”

Aaron and Young spent the afternoon fielding questions from athletes on baseball, but more so on growing up in the civil-rights era. Aaron said he was impressed by that.

Young described how the Braves changed Atlanta when they arrived in 1966, with Aaron already a part of the organization. In the context of it also being the final years of the civil-rights movement, it represented a significant culture change.

“The city decided it was going to be a city too busy to hate,” Young said. “Bringing the baseball team in was one of the ways saying that Atlanta was going to be a big-league city.”

Of course with Aaron, everyone wanted to know about the night he hit his 715th home run in a 7-4 win over the Los Angeles Dodgers. Jerry Royster, who spent 16 years playing major league baseball, stood up and told Aaron he was in the dugout with the Dodgers that night. Even with the opposing team, he was so excited when the ball sailed over the fence he said that he jumped up and hit his head on the roof of the dugout.

Aaron didn’t spend much time reflecting on how he felt when he broke Babe Ruth’s record, but recalled the moments that were the most important to him.

“It was a great night, and after it was over with, my wife and I went home to pray and thank the Lord for blessing us,” Aaron said.

When Prince Deboskie from Chandler, Arizona, asked Aaron what it was like being a black baseball player during his era, he had a lot to say.

As a teenager, Aaron saw Jackie Robinson break the game’s color barrier. The early days for black players in baseball were tough, he said.

“I felt all alone … (just hoping) they would give me an opportunity, just a chance,” Aaron said.

He recalled a time he skipped school to go to one of Robinson’s events for youth baseball players. While he doesn’t recommend the athletes today do the same, he does feel good knowing in some ways it’s come full circle for him.

The athletes will take the field at 9 a.m. Saturday for the game. Aaron passes on his perspective, hoping the athletes walk away from the week’s events with the same values he’s learned.

“Baseball is a promise to some of us, and sometimes its promise to none of us,” Aaron said. “But the most important thing is to do the very best that you can.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured