Over the years since he glided down his golden escalator to announce his candidacy for president, Donald Trump has shown us something rare for a politician: He says the quiet parts out loud. Repeatedly, boldly and often defiantly.

The most recent example is Trump’s pressure campaign to push Republicans in Congress to scuttle the border security bill negotiated painstakingly by a bipartisan group of senators. When the deal went down in flames in the Senate, Trump took credit. “Please blame it on me. Please,” he told a crowd of supporters at a rally in Las Vegas a week ago.

Trump wants to stir the border crisis to the boiling point, all the better to use as what he sees as a potent campaign weapon against President Joe Biden.

Trump’s act of political sabotage reminded me of a moment in American political history when a candidate for president worked to undermine a solution to one of the most divisive and deadly chapters in American history — the secret plot hatched by Richard Nixon in 1968 to cripple negotiations that might have brought an end to the war in Vietnam.

To be clear, I understand that Nixon’s scuttling of a plan to end an American war exists on a scale of magnitude greater than Trump’s interference in the border security agreement. But the comparison is instructive because Nixon and Trump shared the same instinct for wanting to allow a dangerous crisis to continue in service of winning an election.

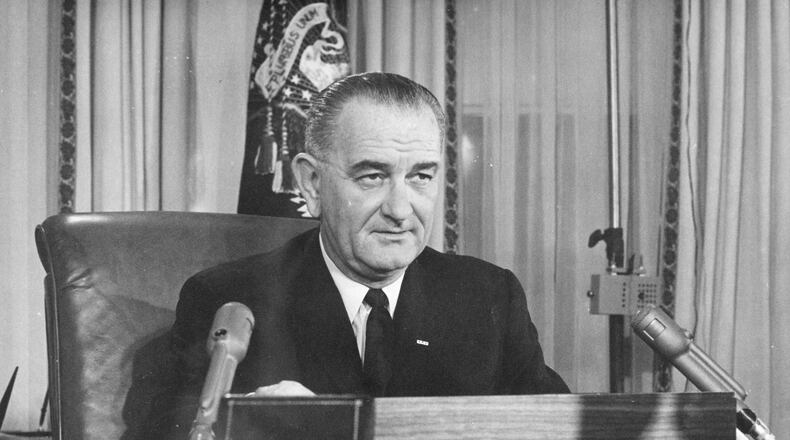

To understand what happened in the Nixon episode, you have to start on the night of March 31, 1968, when President Lyndon Johnson shocked the nation by declaring in a live television speech that he wouldn’t run for reelection. My friend Tom Johnson — who would later serve as the publisher of the Los Angeles Times and go on to become the president of CNN — was standing behind the cameras and technicians in the Oval Office watching the speech.

Tom grew up in Macon, was a student at the University of Georgia, and after going to Harvard Business School, was chosen to be in the first class of White House Fellows. Under the tutelage of press secretary Bill Moyers, Tom became an indispensable aide to the president.

I’ve had several long conversations with Tom about the night of that fateful Johnson speech and what followed. I asked him once whether he recalled the president’s demeanor after the television lights went out and he stepped out from behind the Resolute Desk.

“Relieved,” Tom told me. “Like a huge burden had been lifted from his shoulders.”

Johnson’s recurring heart issues were a key reason he decided not to run for reelection. And as Tom told me, Lady Bird Johnson feared her husband’s heart couldn’t withstand the terrible toll the Vietnam War was taking on American military personnel.

“She really did want them to go back to Texas and get away from the incredible stress that just was consuming him day and night — from the nightly reports of which planes did not return to their carriers or the daily body counts of how many men we had lost,” he said.

As Tom explained it, Johnson wanted to extend an olive branch to the North Vietnamese to establish a path to peace talks. To do that, he’d concluded that if he remained a candidate for reelection, the leaders of both North Vietnam and South Vietnam would see a peace overture as a disingenuous political gambit. So he signaled his sincerity by declaring he’d abandon his campaign for reelection. And on that same night, he also announced a temporary halt to the massive bombing campaign that had inflicted untold destruction on North Vietnam.

Tom recalled the response to the speech from the North Vietnamese: “On March 31 he makes the decision. On April 3 Radio Hanoi broadcasts a report that it is ready to meet. And so it had worked!”

But as efforts to advance the peace talks faltered during the summer of 1968, Johnson learned a secret: The Nixon campaign was working to delay the talks by sending an emissary to whisper in South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu’s ear that if he held off, he’d get a better deal when Nixon became president. The conduit between the Nixon campaign and Thieu was Anna Chennault, a Chinese-born Republican fundraiser. Her role in the trickery gave the episode its name, “The Chennault Affair.”

Tom described LBJ’s reaction to learning of Nixon’s back-channel effort: “President Johnson considered it treason,” he said.

The information was conveyed to Vice President Hubert Humphrey, but Humphrey decided against using it because the country “had already been through too much in 1968.” He knew it might cost him the election, and it did.

Tom acknowledged there’s no sure way of knowing how much sooner the war might have ended if the talks had continued. But it wasn’t until January of 1973 that all sides reached a peace agreement — almost five years after Johnson tried to begin the process with his historic speech.

Today, with the bipartisan border bill dead and buried, both Democrats and Republicans agree there is no path forward in the foreseeable future for a solution to a crisis that the majority of Americans say is a risk to the security of the nation.

Despite the difference in scale, Tom agreed there are parallels between Nixon and Trump.

“The more I think about it ... it is absolutely the undermining of a president and members of Congress,” Tom said. Both men, he said, put political ambition above the greater good of the country.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured