Becoming a member of Congress has its perks. Think workouts at the members-only House gym.

But a successful election can also mean leaving behind jobs, businesses, and lucrative contracts, all forbidden by House ethics rules and, in some cases, barred by federal law once incoming congressmen and women take their oaths of office Jan. 3.

According to the rules of the House of Representatives, members must avoid conflicts of interest, especially when it comes to making money beyond their annual salary of $174,000.

While some outside income is allowed, members are generally barred from operating companies, signing onto federal contracts or even having their names on a business.

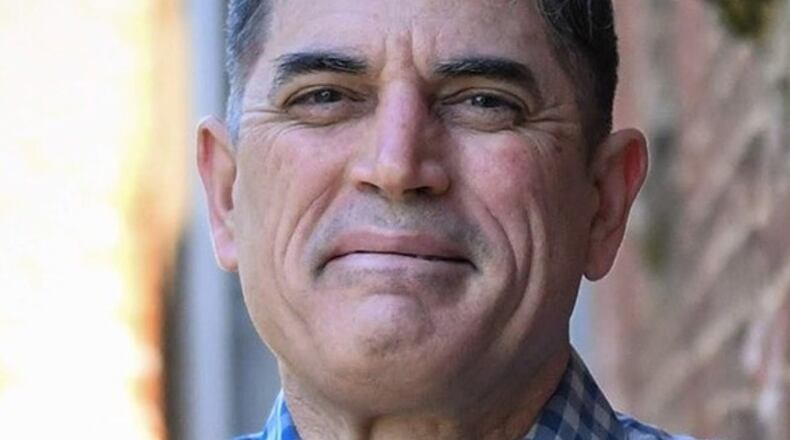

One of Georgia’s four incoming members of the U.S. House, Republican Andrew Clyde, runs two successful gun stores in Georgia, along with a large government contracting business that sells weapons and ammunition to law enforcement agencies.

“As I make my transition to serve in Congress, the operation of my business is being reviewed by my legal team and will be handled in accordance with House ethics rules and guidelines,” Clyde said in a statement.

The other three new members from Georgia said they will be making changes as they shift to the full-time work of Congress. Republican Marjorie Taylor Greene said she is in the process of distancing herself from Taylor Commercial, a family-run commercial construction business which she partly owns.

Democrats Nikema Williams and Carolyn Bourdeaux don’t own own businesses but said they plan to part ways with their employers. Bourdeaux will resign in December from her professorship at Georgia State University, she said. She had been on leave during her campaign for Congress.

Williams said she is winding down her time as deputy director of civic engagement at the National Domestic Workers Alliance - a non-profit advocacy group - and deputy executive director of sister organization Care in Action.

“I’ve already spoken with our executive director and my boss and they understand,” she said recently. “We put a plan in place to start looking for my replacement. We’ve already posted the position, and my plan is I’m leaving in December.”

Williams said she has not yet decided if she will step down as chairwoman of the Democratic Party of Georgia, a volunteer position she can legally keep. That decision will come after the Jan. 5 U.S. Senate runoffs in Georgia, she said.

Members of Congress frequently work in leadership positions of political parties, but federal law bars members from using federal resources, including office space, cell phones, and even postage, for political purposes.

Donald Sherman, deputy director of Citizens for Ethics and Responsibility in Washington, said ethics laws bar members from government contracting and operating businesses to prevent conflicts of interest between what’s best for members’ finances and what’s best for taxpayers and their constituents.

The goal is to eliminate conflicts since members are often asked to weigh in on policy decisions that can impact many business and industry sectors. But there is no rule telling members exactly when they should recuse themselves from voting on matters that impact their own finances.

“The challenge with legislators is that there is no good mechanism for recusal,” Sharman said. “Recusing themselves from votes or from committee action in one area deprives their constituents of representation on an important matter that affects them.”

Members of Congress are allowed to buy and sell stock in individual companies. The STOCK Act, which became law in 2012, prohibits members from using information from their jobs in Congress to decide which stocks to buy and sell.

In an October interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Clyde described the scope of his business before being elected in the 9th Congressional District in northeast Georgia with 78.6% of the vote.

Along with two brick-and-mortar locations and a contract with the federal government, Clyde said, “The law enforcement side truly serves every state of the union, from Alaska to California to the Northeast states and then all the southeastern states and everything in the middle. Even Hawaii.”

Clyde declined at the time to specify his company’s annual revenue, saying only, “We’re a very successful company.”

A search of public records showed Clyde’s Athens-based Armory has received at least $3.7 million in federal contracts since 2010. The company has been registered as a federal contractor since 2007 and is authorized to sell small firearms and ammunition to federal agencies. The database recorded 252 different transactions with Clyde Armory over the years. Clyde’s business also sells to several state agencies in Georgia.

Greene’s spokesman said she is aware of the need to create distance from her family-owned company. Taylor Commercial, based in Alpharetta, was founded in 1969 by Robert Taylor, the Congresswoman-elect’s father. He later sold the company to his daughter and her husband, Perry Greene.

“Like many new members who have family businesses, this is a normal and a common process,” spokesman Nick Dyer said. “Just like other incoming freshman, Congresswoman-elect Greene is complying with all ethics rules and actively seeking advice and counsel to ensure she fulfills all requirements.”

Dyer did not respond to follow up questions about what options Greene is considering. On Taylor Commercial’s business registration paperwork filed with the state, Greene is listed as the company’s corporate secretary. Her husband is its chief executive.

The business specializes in single- and multi-family homes.

The House Ethics Committee occasionally grants waivers to members of Congress to work outside the Capitol. For example, House rules allow doctors in the House to practice medicine, with some restrictions.

Exceptions often also apply to family businesses and unpaid roles at companies.

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured