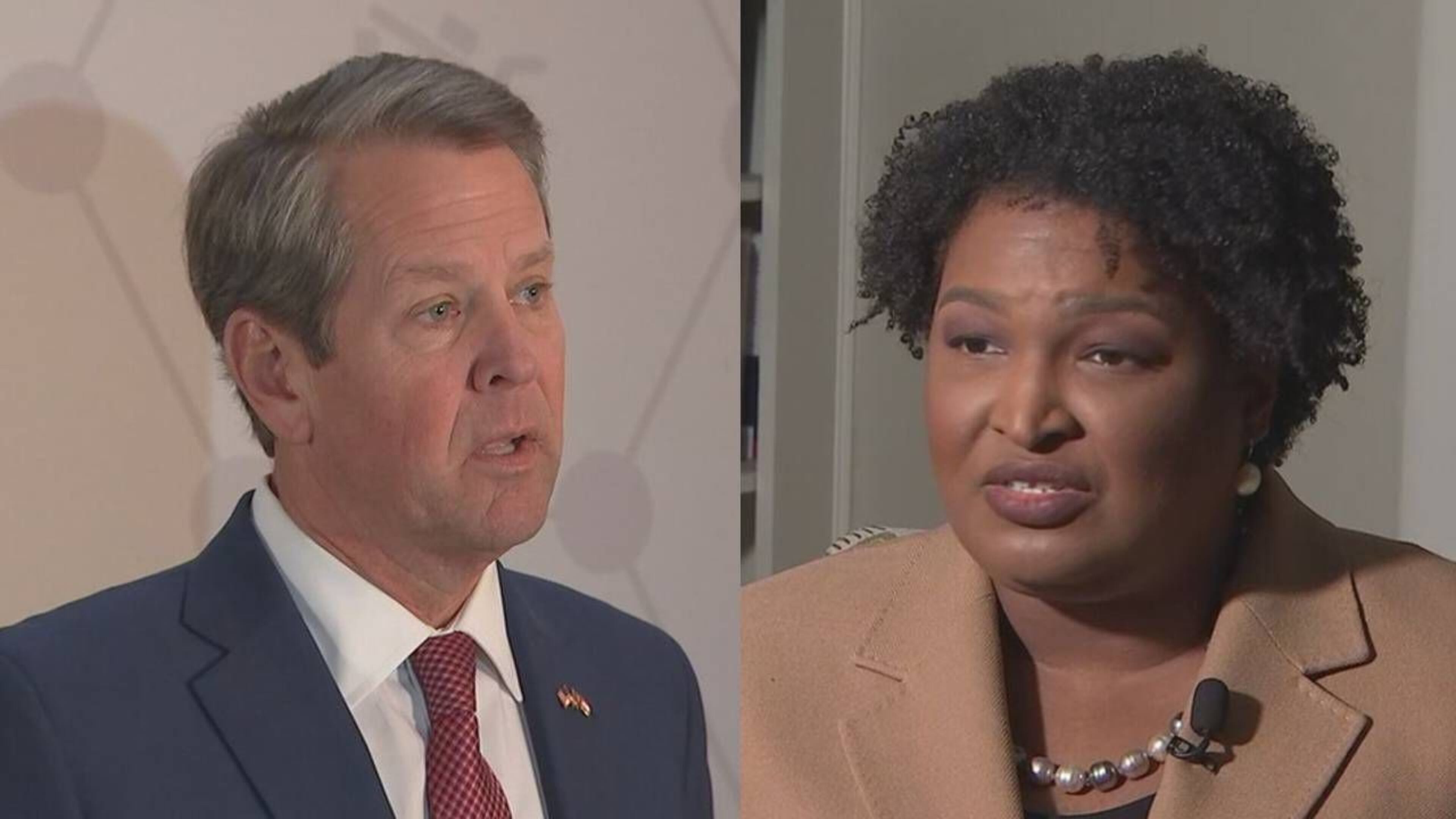

Law designed to help Kemp proves fundraising boon for Abrams too

Knowing Democratic challenger Stacey Abrams could rake in unprecedented campaign money, Republican leaders in the General Assembly last year pushed through a bill designed to give Gov. Brian Kemp a distinct advantage through newly legal fundraising committees without donation caps.

The law made it so Kemp would be the only candidate for governor who could create such a “leadership committee” last year.

But the law of unintended consequences may be at work in 2022.

In just a few days in March — after Abrams filed to run against Kemp — her “leadership committee” collected three contributions totaling $3.5 million. Then the state ethics commission told her committee to stop raising any more until after she wins the Democratic nomination Tuesday.

That’s far more than Kemp’s leadership committee raised from Feb. 1 through April 30, when either the General Assembly was in session or the governor was considering what legislation to sign into law. It’s not far off the $4.7 million Kemp’s committee has raised in total since its creation in July.

The $3.5 million may not account for all the donations to Abrams’ committee. The fund hasn’t filed a campaign disclosure because the ethics commission temporarily shut it down and the candidate is known for collecting thousands of small-dollar contributions from across the country.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution found the big donations by reviewing campaign reports filed by political action committees that gave to the fund.

They show what a power Abrams’ One Georgia fund could be after she wins the nomination and begins her general election campaign.

“Abrams’ vision is widely supported, and she will be a formidable fundraiser, through a leadership PAC or otherwise,” said state Sen. Elena Parent, D-Atlanta, who opposed the leadership committee law.

John Watson, a Capitol lobbyist and former head of the Georgia Republican Party, said the GOP knew Abrams would have no problem raising money, so the leadership committee law won’t necessarily make a difference.

“Whether it’s the leadership committee or a different entity ... it has always been a known predicate to this race that (financial) resources would never be a problem for Stacey Abrams,” he said. “She’s got more money than God, and that is going to continue.”

Changing the law

With her national following, Abrams spent a record $27 million in the 2018 governor’s race, outraising Kemp despite the fact that Georgia had been a reliably Republican state in major races since the early 2000s. In the election, Kemp won a narrow victory anyway.

After the election, the voting rights group Abrams founded, Fair Fight, created a national fundraising machine of its own, taking in more than $100 million by last year and helping to fuel Democratic Party efforts in states across the country during the 2020 elections, including in Georgia. Abrams and the organization were credited with helping Democrats win Georgia for Democrat Joe Biden in the presidential race and flip two U.S. Senate seats.

So last year, over opposition from Democrats in the General Assembly, Republican leaders passed legislation to let the governor, the opposing party’s gubernatorial nominee, the lieutenant governor and party caucuses create special leadership committees to raise as much cash as they can, without limits for individual donors.

It gave Kemp an added edge since challengers weren’t supposed to be able to use the funds until they won their party’s nomination. The governor’s campaign, meanwhile, was the first to create a committee and began raising money last summer, right after the bill became law.

Statewide candidates, such as those running for governor, are currently allowed to raise $7,600 from individual donors for the primary and again for the general election, plus $4,500 per runoff.

Those limits don’t apply to leadership committees. So, for instance, a company or business association seeking a tax break from the General Assembly could give $100,000 or more to such funds and do it while lawmakers are considering the tax break or while the governor is deciding whether to sign it into law.

Kemp’s committee has reported numerous contributions ranging up to $250,000. The donors included many individuals and companies with a big interest in what goes on at the Capitol.

The law also allows leadership committees to coordinate their activities with a candidate’s campaign, something other fundraising entities such as PACs aren’t allowed to do under Georgia law. It essentially allows select candidates to circumvent fundraising caps that apply to most people running for office.

Parent said the reason for the law was clear.

“Gov. Kemp and his GOP enablers created the corrupt leadership committee scheme to try to give him an unfair financial advantage over all challengers,” she said.

U.S. District Judge Mark Cohen acknowledged the edge last month when he ruled Kemp’s committee had to suspend fundraising unless he wins the Republican nomination next week. Unlike Abrams, who is running unopposed in her primary, Kemp faces former U.S. Sen. David Perdue — ex-President Donald Trump’s candidate — in the GOP primary.

Cohen ruled that the leadership committee law gave Kemp an unfair advantage by allowing only the incumbent to create a fund before the primary.

Abrams created one too in early March, arguing that she was the nominee since no other Democrat was running. But the judge ruled last month that Abrams could not raise money through a leadership committee until she wins her party’s primary. That’s essentially what the ethics commission staff had told her campaign in March.

David Emadi, executive secretary of the state ethics commission, said the Abrams camp could keep contributions it raised in those first few days after she qualified but could not spend the money until after the primary.

An AJC review of campaign reports shows Abrams’ leadership committee got three big contributions in the days after qualifying:

- $1.5 million from Fair Fight PAC

- $1 million from a super PAC funded by billionaire megadonor George Soros.

- $1 million from the Washington-based Democratic Governors Association

Those individual contributions were much larger than any given to Kemp’s leadership committee.

The leadership committee figures are on top of record fundraising amounts Abrams and Kemp have already collected through their regular campaign accounts. Outside groups, such as the Republican and Democratic governors associations, have committed to spending big in Georgia as well.

But the individual candidate accounts can’t legally take in $1 million donations, and the outside groups can’t spend money in direct coordination with a candidate’s campaign.

Watson said Abrams’ supporters across the nation would find a way to pour big money into her campaign regardless — with or without the leadership committee law. So Republicans know what they are up against.

“If there was not a leadership committee, those same people would still be writing checks,” he said. “The check and the dollar amount were coming anyway.”