Opinion: What I owe John Lewis for his brave work

You might not know it to look at me, but I’m personally indebted to John Lewis for the greatest accomplishment of his life’s work – giving African Americans in the South the right to vote.

I served five terms in Congress. Each time I was elected by a biracial coalition of voters. Each time I had to win a primary election that was dominated by Black voters, and a general election that was dominated by white voters. None of that would have been possible without the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and the Voting Rights Act would not have been possible without John Lewis.

It’s pretty obvious how the Voting Rights Act made it possible for folks like Andrew Young, John Lewis, Sanford Bishop, David Scott, Hank Johnson, and Lucy McBath to get elected to Congress. What’s not so obvious is how his work also made it possible for folks like Buddy Darden, Jim Marshall, Don Johnson, Elliott Levitas – and me – to have the same opportunity.

Although folks like us were never considered the primary beneficiaries of expanding the franchise, we were beneficiaries nonetheless. Our service in Congress would never have been possible if John Lewis hadn’t made it possible.

Like my parents, I was born with every opportunity for public service within the gift of my home town. But in the society in which John Lewis and I were born, no one who believed what my parents taught me – that every citizen should have the free and equal right to vote – could expect to attain high political office. Not in a state where the politics of one race was devoted almost exclusively to denying the other race the right to vote.

In helping us lay down the burden of racial discrimination in voting, John made it possible for our part of the country to move forward on virtually every front. He did it by making it possible for political candidates to compete for the support of like-minded voters – without regard to color. And biracial voting coalitions benefit us all.

So, on behalf of all of the beneficiaries of the right to vote – black and white – I owe a great debt of gratitude to John Lewis.

John’s work is far from over – it may, in fact, never be completely finished. For one thing, voter suppression at the retail level can be even more insidious than at the wholesale level, if only because it’s harder for some folks to see. After all, it’s very hard for anyone to see that there’s anything wrong with anything that tips the scales just a little bit in their favor. In fact, the littler the better – because it’s easier to get away with.

For example, we all see voter suppression when African American citizens are subjected to ridiculous “tests” not given to white citizens. But who sees voter suppression when it is practiced at the margins?

Consider the allocation of voting resources in such a way that voters in some precincts have to wait for hours and hours to vote while the rest of us can get in and out of the polls in 20 minutes. Or a voter “purge” program that relies on a post card – one lousy postcard – to determine if you get to stay on the voting rolls. We know from experience with the census that this process has an error rate in excess of 25% (which is why we employ census takers to follow up on census mailings). Do these things matter? They did to John Lewis.

These may be little things compared to the billy clubs and “soap bubble tests” used to keep vast numbers of citizens off the voting rolls. But John Lewis knew that little things mean a lot, especially in close elections.

This year we were inspired not only by John’s life-long fight for the rights for others, but also by his fight against cancer. It was just one more example of the courage that has benefited so many, and which will continue to benefit so many for years to come. But for me, I will always remember the loving kindness he showed everyone he met.

When I ran for Secretary of State a couple of years ago, Angèle and I visited with John to ask for his help. He did not hesitate to endorse my campaign, and he helped in many ways. But he was far more interested in our kids, and in how we had joined our lives together after I had left Congress. He knew what it meant to lose the ones we love, and to love the ones we’ve lost. He had lost his wife of 45 years just six years earlier. His sheer delight in our happiness was palpable – and was a great gift to us both.

This was characteristic. John didn’t just love “the people,” he loved people. That love was the source of his strength as a person and as a politician. No one could put the “love” in the Beloved Community like John Lewis did.

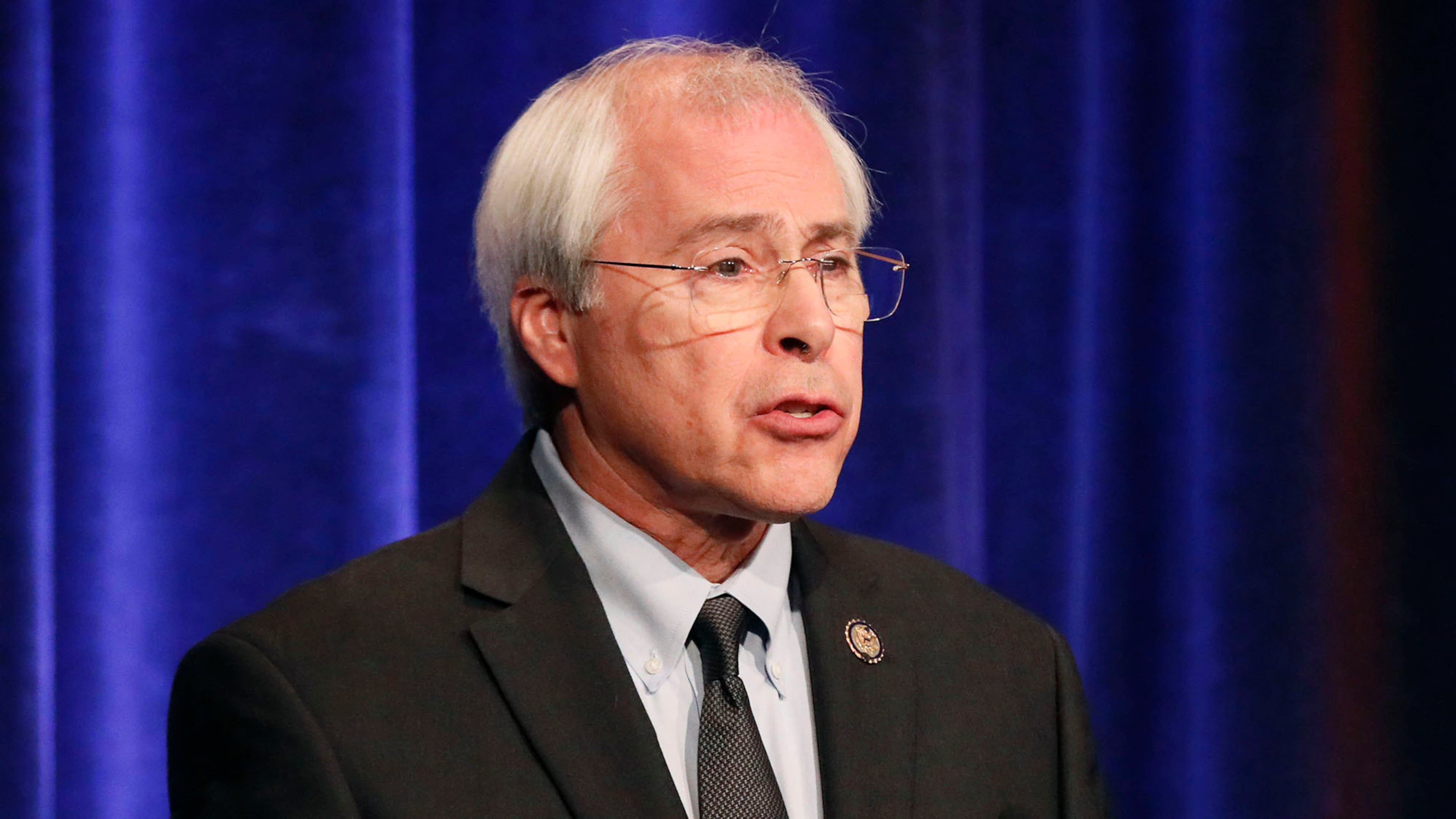

John Barrow is a former U.S. Congressman.