In one giant classroom, four teachers manage 135 kids – and love it

What You Should Know

- Across the country, schools are facing high turnover among teachers.

- In Mesa, the largest school system in Arizona, teachers are experimenting with a new model.

- Known as “team teaching,” teachers share large groups of students.

- The concept is showing promise, and the idea is spreading to other school districts in Arizona and beyond.

A teacher in training darted among students, tallying how many needed his help with a history unit on Islam. A veteran math teacher hovered near a cluster of desks, coaching some 50 freshmen on a geometry assignment. A science teacher checked students’ homework, while an English teacher spoke loudly into a microphone at the front of the classroom, giving instruction, to keep students on track.

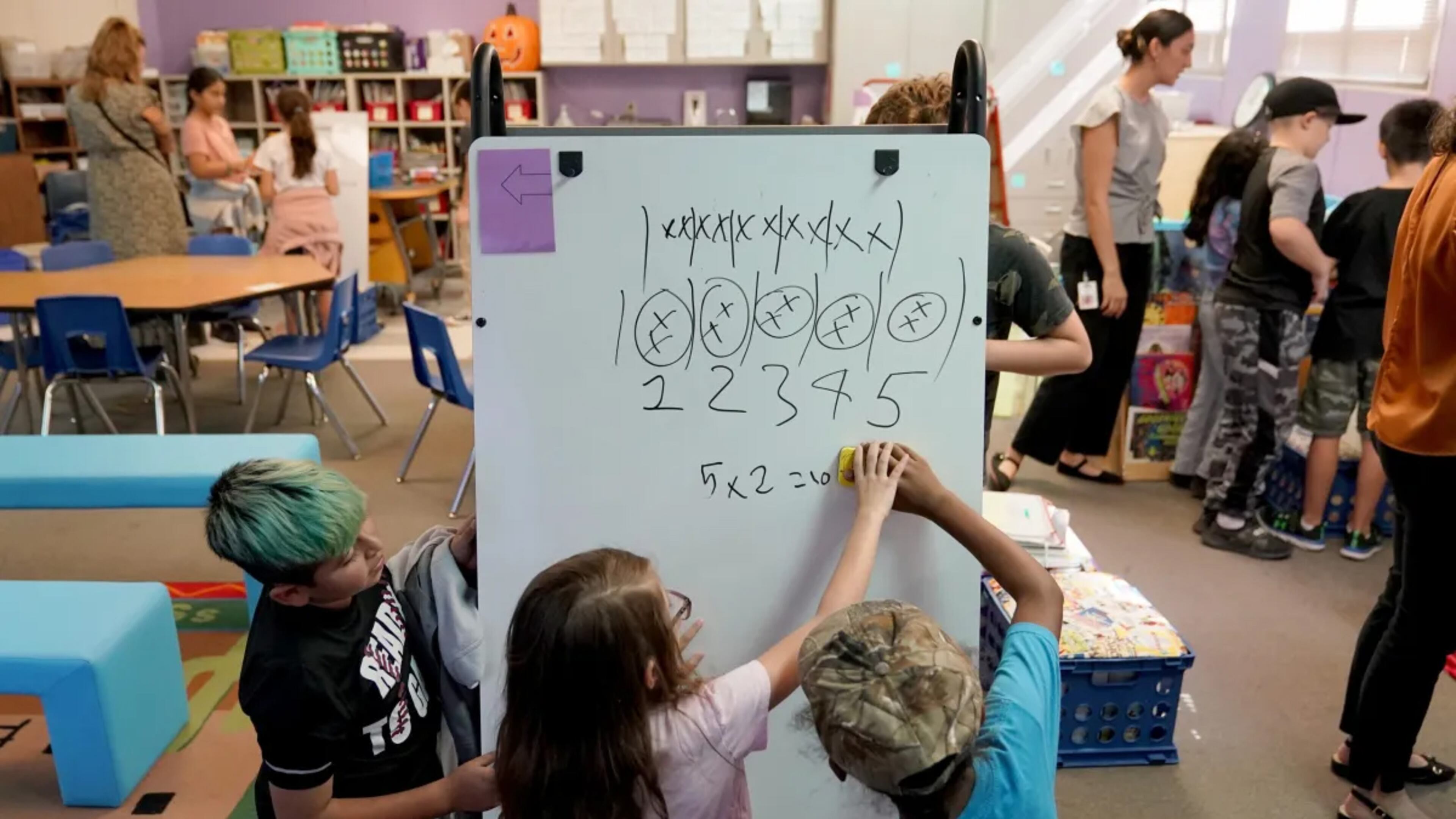

One hundred thirty-five students, four teachers, one giant classroom.

This is what ninth grade looks like at Westwood High School, in Mesa, Arizona’s largest school system. There, an innovative teaching model has taken hold and is spreading to other schools in the district and beyond.

Five years ago, faced with high teacher turnover and declining student enrollment, Westwood’s leaders decided to try something different.

Working with professors at Arizona State University, they piloted a classroom model known as team teaching. It allows teachers to voluntarily dissolve the walls that separate their classes across physical or grade divides.

The teachers share large groups of students – sometimes 100 or more – and rotate between big group instruction, one-on-one interventions, small study groups or whatever the teachers as a team agree is a priority that day.

What looks at times like chaos is in fact part of a carefully orchestrated plan: Each morning, the Westwood teams meet for two hours to hash out a personalized program for every student on their shared roster, dictating the lessons, skills and assignments the team will focus on that day.

By giving teachers more opportunity to collaborate and greater control over how and what they teach, Mesa’s administrators hoped to fill staffing gaps and boost teacher morale and retention. Initial research suggests the gamble could pay off.

This year, the district expanded the concept to a third of its 82 schools.

The team-teaching strategy is also drawing interest from school leaders across the U.S., who are eager for new approaches at a time when the effects of the pandemic have dampened teacher morale and worsened staff shortages.

“The pandemic taught us two things: One is people want flexibility, and the other is people don’t want to be isolated,” said Carole Basile, dean of ASU’s teachers college, who helped design the teaching model. “The education profession is both of those. It is inflexible, and it is isolating.”

Team teaching, she said, turns these ideas on their head.

Reversing low morale

ASU and surrounding school districts started investigating team teaching about six years ago. Enrollment at teacher preparation programs around the country was plummeting, as more young people sought out careers that offered better pay, more flexibility and less stress.

Team teaching, a concept first introduced in schools in the 1960s, appealed to the ASU researchers because they felt its unusual staffing structure could help revitalize teachers. And it resonated with school district leaders, who’d come to believe the model of one teacher lecturing at the front of a classroom to many kids wasn’t working.

“Teachers are doing fantastic things, but it’s very rare a teacher walks into another room to see what’s happening,” said Andi Fourlis, superintendent of Mesa Public Schools, one of 10 Arizona districts that have adopted the model. “Our profession is so slow to advance because we are working in isolation.”

Of course, revamping teaching approaches can’t fix some of the biggest frustrations many teachers have about their profession, such as low pay. But early results from Mesa show team teaching may be helping to reverse low morale.

In a survey of hundreds of the district’s teachers last year, researchers from Johns Hopkins University found that those who worked on teams reported greater satisfaction with their job, more frequent collaborations with colleagues and more positive interactions with students. Data on the impact on teacher vacancies, however, remains limited.

‘A good thing’

School districts that have adopted the model are meanwhile beginning to collect data on its impact on students. A district in southeastern Arizona randomly assigned children to classrooms with the team-teaching model, to test whether it improves student performance. Early data from Westwood show on-time course completion – a strong predictor of whether freshmen will graduate – improved after the high school started using the team approach for all ninth graders.

ASU has found that students in team-based classrooms have better attendance, earn more credits toward graduation and post higher GPAs.

The model, though, is not for everyone.

Peggy Beesley, a math teacher now in her fifth year with Westwood’s team, has tried to recruit other math teachers to volunteer for a team, but many tell her they prefer to work alone. Team teaching can also be a scheduling nightmare, especially at schools like Westwood where only some staff work in teams and principals have to balance their time and needs with those of other teachers.

School leaders in Mesa stress they would never force teachers to participate on a team; the district only plans to expand the model to half of its schools.

Quinton Rawls attended a middle school with no teams and not enough teachers. Two weeks into eighth grade, his science teacher quit and was replaced by a series of subs. “I got away with everything,” recalled the 14-year-old.

That’s not the case in ninth grade, said Rawls. He said he appreciates the extra attention that comes with being in a class with so many teachers at once.

“There’s four of them watching me all the time,” he said. “I think that’s a good thing. I’m not really wasting time.”

About the Solutions Journalism Network

This story is republished through our partner, the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous reporting about social issues.

Neal Morton