A spectacle that’s played for a decade seemingly came to an end this week when the city of Atlanta vowed to cut huge checks to three homeowners who live near the former Braves stadium.

Two families in the Peoplestown neighborhood will get $1.9 million each and a third will receive nearly $1.5 million so the city can bulldoze their homes and build a water detention pond and a park. The project was originally supposed to take care of chronic flooding in the area but morphed into a plan to take an entire block of homes to build a Japanese-style park, complete with a pagoda, in an area being gentrified. The park has since been scaled back.

On the surface, this is a simple case of eminent domain, of government taking private property to build something for public use. It happens all the time to build highways, parks and even stadiums. In fact, the nearby interstate and the two ballparks built for the Braves (and Falcons) decimated the area and ran off thousands of mostly Black residents. Perhaps this was a small payback to harms long past.

The latest battle was a drama that pitched almost all the elements that loom large in Atlanta: Politics, race, power, protest and, ultimately, money.

The very loud and contested proceedings started in 2014 under Mayor Kasim Reed’s administration, carried on through Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms’ four years and then into the term of Mayor Andre Dickens, who finally agreed to spend more than $6 million for the problem to go away. (In June, a fourth homeowner got a $925,000 buyout.)

The settlement figures are amazing considering they are 10 times the cost of what homes there were a decade ago and four times the current value as the neighborhood has become hot.

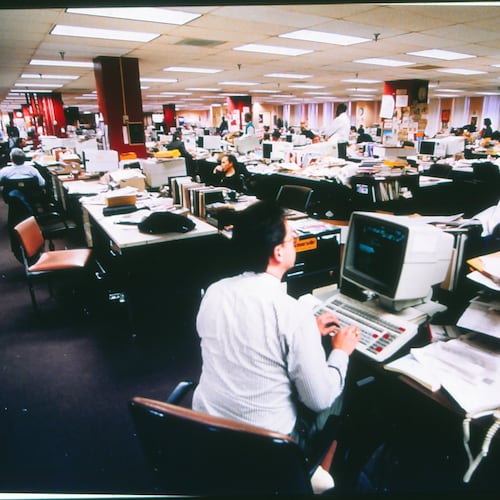

Credit: Bill Torpy

Credit: Bill Torpy

The three remaining holdouts contesting condemnation couldn’t have been cast better by Hollywood directors if you wanted to shoot a picture about fighting City Hall, especially Atlanta City Hall:

— There was the late Mattie Jackson, a 90-something matriarchal figure who had generations of politicians darkening her doorway to gain her support. (Interestingly, she even helped the city with some eminent domain as the Olympics approached.)

— There was Tanya Washington, a law professor/activist who is not afraid of microphones.

— And there were the Dardens, a retired working couple who have been a presence in the community for decades.

Washington and the Dardens got the larger settlements, because they bore most of the cost of six years of litigation.

Another subplot in this saga is that the running controversy probably put a stake in the heart of Kasim Reed’s political comeback last year and got Dickens elected.

Bertha Darden confronted Reed at a candidate forum just days before the 2021 mayoral election. The event was winding down and Reed was antsy to leave, especially when he eyed her walking to the podium. She then tore into him, talking emotionally about lies and trust. The anti-Kasim forces — and they were many — quickly distributed the video, complete with a syrupy musical soundtrack, and Peoplestown became a last-minute election issue.

Dickens, an underdog in the multi-candidate race, leapt over Reed for second place by 600 votes (with about 44,000 collective votes between them). Once in the runoff, Atlanta’s old-timey Black political machine and white progressives coalesced around Dickens and front-runner Felicia Moore was toast. If it was Moore versus Reed in the runoff, I’d bet you a paycheck Moore would be mayor.

Aside from the politics, the protest placards and the chanting at City Hall, a story like this needs a good lawyer. The families brought in Don Evans, an eminent domain lawyer from Cartersville, and the city and Evans swapped motion after motion in court.

Evans, as had Washington early in the case, contended that perhaps only a handful of homes needed to be taken for a detention pond, not 27.

“They never had to do that,” Evans told me. “They never did a proper analysis until 2018 after they had already been proceeding.”

The homeowners argued the city kept revising the engineering plans for the project as the years went on.

Most of residents’ homes were bought by 2016, after the city told homeowners they had to go. Davy Jones lived down the block from Mattie Jackson for eight years and left after receiving about $280,000. The recent settlement figures are surprising, he said. He was dismayed to see Washington, who moved into her home in 2011, get so much although he can see how the others got what they did.

Evans said the whole thing is a tragedy. “People have lived there for a generation and missed out on the greatest (home) appreciation in memory,” he said.

The lawyer noted there were about $300,000 in engineering fees. I asked if he got the normal third in attorney’s fees, and he said I was in the ballpark.

Dickens noted this was a “critically needed project to protect the larger community,” and he wanted to be a problem solver. “I know these families wanted to stay in their homes, and I am grateful for the sacrifice they are making for the larger community and our city.”

In addition to writing big checks, Dickens should also give Mrs. Darden a big hug and a Candygram for helping make him mayor.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured