Vietnam POW seeks healing at infamous Hanoi Hilton

When retired Lt. Col. James W. Williams returned to Southeast Asia this past fall, to the site of the worst 313 days of his life, the last thing he expected to find was himself.

For a period spanning 1972-1973, Williams, a former U.S. Air Force pilot, was a prisoner at the infamous Hanoi Hilton.

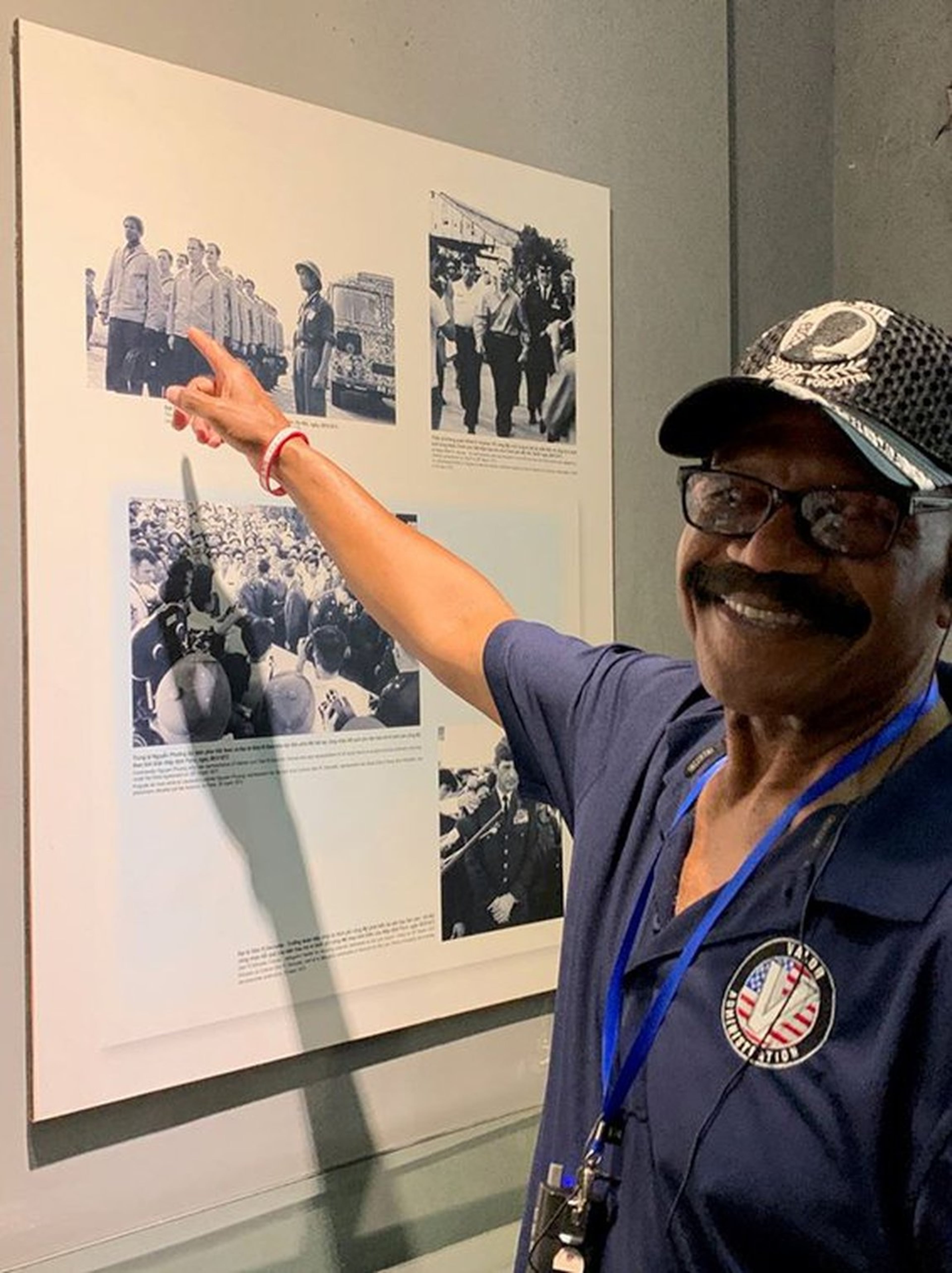

As he walked through what’s left of the prison, now a propaganda-filled museum, someone stopped him in his tracks and pointed at a photograph on the wall.

There he was.

Tall. Handsome. Full afro. The only black soldier, he was leading a line of POWS, the last to leave, out of Vietnam.

“I had never seen that photograph before,” the Norcross resident told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “Looking at it, I get a flashback, thinking about how happy we were to be going home. It was rough in there, but we knew that our day was coming.”

At the time the photograph was taken, Williams wouldn’t have been able to imagine coming back to the prison voluntarily. But, in October, he was one of a handful of Vietnam veterans who returned to Hanoi in a trip organized by Valor Administration, a Dallas-based group that supports combat veterans and their families.

The mission back to Vietnam was designed to help veterans who are still struggling with some level of post-traumatic stress disorder. The hope is that they’ll reach closure by seeing the place of their greatest trauma in a different light.

The group met with several former North Vietnamese veterans.

“The idea is to be able to return to the place where you served your country and see it during peacetime,” said Adriane Baan, Valor Administration’s secretary. “It gives them a reframing of the whole experience. There are a lot of Vietnam veterans that still have wounds from the war that haven’t been addressed.”

Williams is 75 years old now. He’s twice retired — first from the Air Force in 1995 after 28 years of military service, then from a 20-year career with DeKalb County, where he started an Air Force Junior ROTC Program at Tucker High School in 1996.

Nowadays, he spends most of his time following the Atlanta Falcons, supporting his alma mater Tennessee State University and chasing after his 10 grandchildren and one great-grandson.

“If there’s anything I learned from Lt. Col. Williams, it’s that we, as human beings, are capable of so much,” Lt. Col. Nick Callaway, the commander of TSU’s Air Force ROTC Detachment 790, which Williams was a member of as a student in the 1960s. “Lt. Col. Williams’ patriotism and devotion to this great nation is truly an inspiration.”

From Tennessee State to the Hanoi Hilton

Born in Memphis, the oldest of five, Williams was the first in the family to go to college, picking Tennessee State in 1962, where he was a classmate of Olympians Wyomia Tyus, Edith Duvall, Wilma Rudolph and Ralph Boston.

He pledged Kappa Alpha Psi and, because it was mandatory on campus in those days, joined the ROTC.

Williams graduated from TSU on March 17, 1967 and was commissioned in the Air Force on March 20. He began active duty on April 30.

Williams was flying his 228th combat mission on May 20, 1972, when his F-4D Phantom was hit over North Vietnam while escorting a group of bombers. He was 40 days shy of ending his tour.

“I had gotten used to being shot at. But, on this particular mission, we were fully engaged,” Williams said.

He and his partner were able to eject before their plane crashed. They separated because they thought it would be safer.

Williams searched for cover and waited five hours for help. But armed with just a radio and a .38, and covered with leeches, he soon found himself surrounded by a dozen villagers with machine guns.

They beat him, stripped him naked and marched him back to the village.

The locals had never seen a black man, so he was paraded through the village.

Between beatings, he would be awakened by curious children, who would sneak up on him and touch his hair before running away shrieking.

After two days, the villagers turned him over to the Vietnamese army.

He would find out later that his partner had been rescued. Williams was taken to the infamous Hỏa Lò Prison, where he would spend the next 10 months.

The late U.S. Sen. John McCain also had a room at the ironically nicknamed Hanoi Hilton.

The white man’s war?

Williams’ captors put him in an isolated cell about the size of a bathroom, with a concrete bunk.

He initially had no contact with other prisoners and would often be awakened by beatings and attempts at interrogation.

After 40 days, he was placed in a cell with other prisoners. He was given a pair of flip flops, two uniforms, a red-striped one and a gray one, and a mosquito net to fend off the water bug sized parasites.

“When they walked you in for interrogation, you always had to look up to them,” said Williams, explaining that prisoners were always positioned lower than the jailers. “I would look them dead in the eyes and, eventually, they would turn their heads away. They didn’t like that.”

Williams said of the 662 men housed at the prison, only 16 were black and only seven of them held officer ranks.

“They would ask me, ‘How can you, as a colored man, fight the white man’s war?’” Williams said. “I never answered any questions. So … one of my punishments was that I was not allowed to write home.”

His family didn’t know if he was alive or dead. Williams was listed as missing in action.

Williams’ son, Brandon, said his father’s courage and perseverance while in captivity motivates him when he faces adversity.

“Through any situation or circumstance, don’t give up,” said Brandon, a former TSU football player who is now a financial adviser for professional athletes. “He’s my hero.”

Williams was released with other American POWs on March 28, 1973, about two months after the Vietnam War ended.

Going back to Hanoi

Before going back to Hanoi on Oct. 30, Williams was warned that it was a different place than the one he left. With an estimated population of 7.7 million people in 2018, it is the second-largest city in Vietnam and growing rapidly, thanks to a recent construction boom.

“When I left that place 46 years ago, everything was so different,” Williams said, a member of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs POW Advisory Committee. “It is like a different world now.”

At the prison-turned-museum, Williams sat in some of the old cells, peered into some of the interrogation rooms, had real Vietnamese food and silently reflected on his time there.

Other than discovering his photograph on display, Williams had another surprise waiting.

He met with Nguyen Thi Lam, the widow of Do Van Lanh, the North Vietnamese pilot who shot down his plane.

Williams did not know the meeting was going to take place until he got to Vietnam.

He said the encounter was awkward at first. But that changed the more they talked. He gave her a lapel pin. He can’t remember what she gave him.

“It is all part of the healing process,” said Williams, who suffers from what he describes as “a little PTSD” but manages it. “The trip definitely helped me. It gave me some closure.”