Paul Hemphill on Martin Luther King: The last look

Editor's note: Martin Luther King Jr. was killed by an assassin's bullet on April 4, 1968. This column by Paul Hemphill was originally printed on April 8, 1968.

RELATED: Read and sign the online remembrance book for Martin Luther King Jr.

The line began at the entrance to the campus of Spelman College, and from there it wound like a column of ants around the stark brick buildings and beneath the blossoming dogwood trees and over the fresh green grass of early spring. The line if you walked it off, was precisely 1,700 yards long, and the way the people were bunched up most of the time that meant it was made up of very nearly 7,000 at a time. Most of them still wore the clothes they had worn to church that morning, and the line was a potpourri of spring bonnets and dark suits and unopened umbrellas and sack lunches and children in their mothers’ arms, and it was taking something like four hours to make it to the cavernous chapel where the body of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. lay in a black silk and mohair suit under the glass of a dark mahogany casket.

Johnny Jenkins, like the rest of them, was tired to the bones. He had gotten in line after church, he said. He wore a bright sweater and kept his hands in his pockets and shuffled along as the line slowly moved toward the chapel.

“How long have you been here?” he was asked.

“About six hours,” he said in a whisper.

“You must want to see him very much.”

“Sure. Everybody does. We got to see him one more time.”

“I’d met him once or twice,” Johnny Jenkins said. “But that didn’t matter. See, I’m with the sanitation department for the city. That’s the same people he was trying to help when it happened. So I knew him. Uh-huh. I knew him.”

Gone was bitterness

The story on Palm Sunday was not in the smouldering cities in the North, where cops are working around the clock. The story was not in downtown Atlanta where police dogs and their masters cautiously walked the streets. The story was not in the White House or the offices of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference or even the Ebenezer Baptist Church where, during the morning service, Mahalia Jackson had sung and Dizzy Gillespie had played a Negro slave song called “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” The story was the black people who had come off the streets and out of the slums to stand for hours under the blustery gray sky to see for the last time perhaps the greatest they ever had.

And so the bitterness was gone, at least for a day. There was no fresh news on the assassin. There was no statement from the impatient young ones who want to kill every white man in sight. There were no mysterious fires around town, few arrests, little drinking and certainty no rejoicing. There were these thousands of people shuffling their feet slowly forward and thinking not of what happens next but only of what has happened in the 12 years since Martin Luther King came forward because white people would not let a young Negro seamstress keep her seat on a bus in Montgomery.

»Local and indepth: How the AJC covered the civil rights movement

LEARN MORE: AJC coverage of the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King's assassination

Great sadness inside

By 8 o’clock Sunday night the lights had come on but the people continued to wind around the sidewalks and up the wide steps of Sisters Chapel and down the aisle to the casket, which sat beneath rows of flowers and wreaths. They seemed to stiffen and tighten their jaws as they came closer to the casket, and many of them could glance only for a second before breaking past the casket and quickening their steps until they were outside beneath the budding trees. It was there that many of them would stand for minutes listening to the sound of the organ music drifting from the chapel.

Three of these, two women and a man, all Negroes, were at the foot of the steps to the chapel. The older woman, the mother of the younger one, fought back the tears. “He saved my marriage,” she said.

“You knew him, then?” somebody said to her.

“My husband and me, we were separated and about to get a divorce one time. We’ve got eight kids, from a baby all the way up to nearly 29 years old. Dr. King, he talked to us. Both of us. My husband says it was like being born again, we’re so happy.”

“They catch the man who did it yet?” the man asked.

“Humph,” the woman said. “What’ll they do when they do?”

“He better burn.”

“If they don’t kill him, I think I’ll kill myself.” the woman said. “Life ain’t hardly worth living now that he’s dead.”

Then they moved away, tired from the long wait in line, holding this great sadness inside and they said they would be back Tuesday for the funeral. The line of people, as they walked toward their car, seemed even longer now.

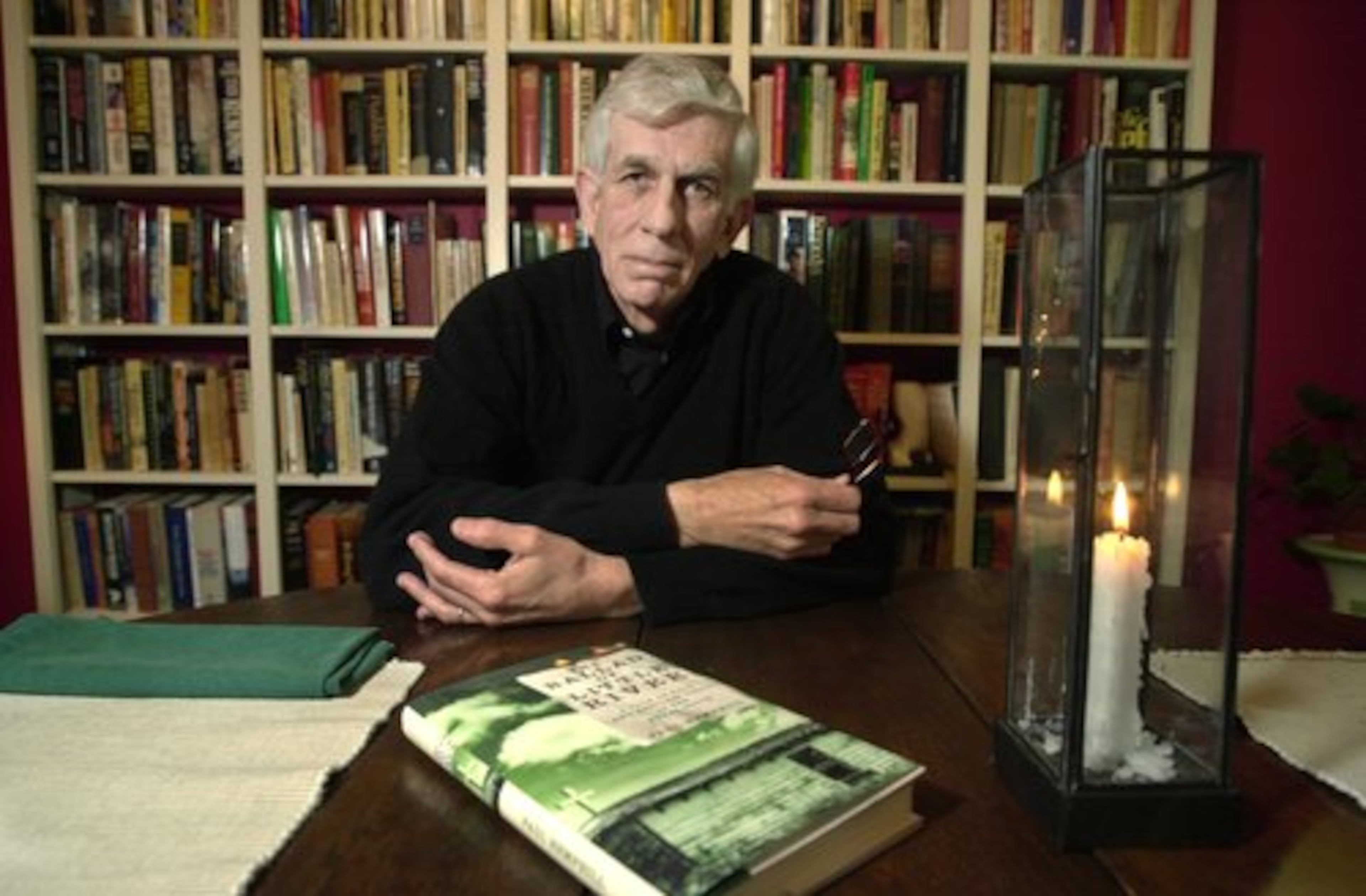

About Paul Hemphill

Paul Hemphill wrote a Page 2 column for The Atlanta Journal that appeared six days a week from 1964 to 1969. His ear for dialogue and easygoing style led some to refer to him as the Jimmy Breslin of the South. After leaving the paper he went on to publish 16 books. He died in 2009 at age 73.

The March 21 documentary 'The Last Days of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.' on Channel 2 kicked off a countdown of remembrance across the combined platforms of Channel 2 and its partners, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and WSB Radio.

The three Atlanta news sources will release comprehensive multi-platform content until April 9, the anniversary of King’s funeral.

On April 4, the 50th anniversary of Dr. King’s assassination, the three properties will devote extensive live coverage to the memorials in Atlanta, Memphis and around the country.

The project will present a living timeline in real time as it occurred on that day in 1968, right down to the time the fatal shot was fired that ended his life an hour later.

The project will culminate on April 9 with coverage of the special processional in Atlanta marking the path of Dr. King’s funeral, which was watched by the world.