I was a young photojournalist in Atlanta when the United States was attacked on September 11. I’d never worked in another country. Like most of my colleagues, I was eager to tell the stories of people impacted here, as well as overseas. I was dying to go.

So when the AJC’s director of photography walked up to me and asked if I’d go to Afghanistan for the one-year anniversary of 9/11, I jumped at the chance.

I had never been to Afghanistan. I had been to Iran, my family’s homeland. Iran and parts of Afghanistan share a similar language and culture. But you can’t compare life in Iran to Afghanistan, which has been ravaged by wars: with the Soviets, with the Taliban, with the British.

I didn’t know what to expect. I was excited to go, but I was also scared. I took solace in speaking Farsi, and knowing that I could communicate with some Afghans. It was also comforting to know I’d be traveling with fellow Cox reporter Margaret “Meg” Coker, a longtime foreign correspondent.

I flew to Dubai and boarded an Ariana Afghan Airlines flight for Kabul. Only a few other women were on board.

Landing in Kabul, I was struck by the runway lights, which looked like a string of bistro lights. When I entered the terminal, it didn’t have power. I handed over my passport to an Afghan immigration official, who returned it, stamped misspelled with “immigrition.” It remains my favorite passport stamp.

Meg met me at the airport with our “fixers” and translators Emal Haidary and Abdullah Baqi, who proved invaluable in helping us navigate the country and building trust with the people we spoke with and photographed. We left immediately for Jalalabad following a narrow mountain road so pockmarked with bomb craters that it took 10 hours to travel 90 miles.

For the next three weeks, we covered the rebirth of a nation, one year after the U.S. invasion. People’s social and economic lives had been ripped apart after decades of war, but signs of hope were everywhere.

Credit: BITA HONARVAR

Credit: BITA HONARVAR

In Jalalabad, we visited markets and makeshift outdoor classrooms. We went to Tora Bora and explored the cave complex in the mountains, still stockpiled with weapons. In Kabul, markets bustled with life as merchants hawked their wares -- bootleg Coca-Cola and American-branded T-shirts -- alongside stores selling traditional rugs and pakols, the soft, round hats worn by so many Afghan men. Young men lifted weights in small, dark gyms. Beauticians did their magic in a storefront salon packed with women readying for a wedding. Boys flew kites from rooftops.

And, most importantly, girls went to school.

Credit: BITA HONARVAR

Credit: BITA HONARVAR

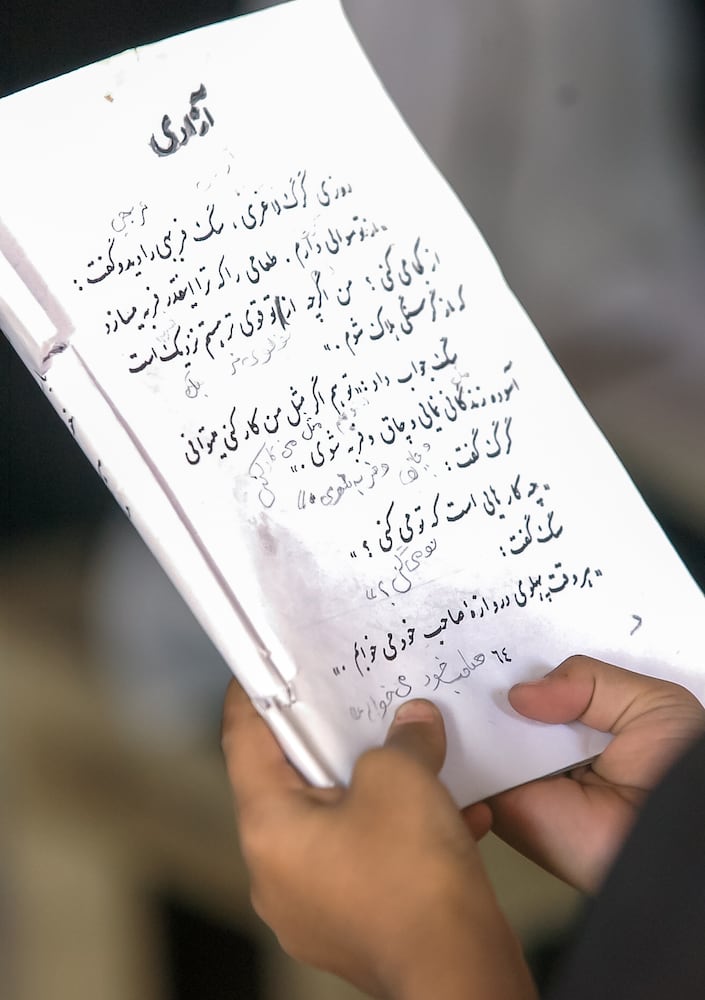

One of the schools we visited had barely anything in the classroom -- no desks, just a chalkboard and benches. The girls shared notebooks and textbooks. But they were so excited to be in a school, learning. As the teachers called on them to talk, or go up to the board and do math, you could see the enthusiasm in their smiles and energy. They were so proud to have visitors to show they were learning how to read and write and do math.

As I look at those photos now, I remember how fascinated they were by my clothing and cameras, so curious to know where I came from and where I was going. I wonder where they are now, and what and how they are doing. Their eagerness for school was real, intoxicating, and offered the greatest promise of hope for the country’s future.

Credit: BITA HONARVAR

Credit: BITA HONARVAR

It’s the girls I now see on TV who break my heart.

I watch, my heart aching, as Afghanistan unravels. Footage of people desperately trying to get to the airport and escape the Taliban. Of men falling to their deaths from airplanes headed away from the impending horror. Of women and girls realizing that what little freedom they had will likely be stolen. Again.

I see reports that the Taliban are already shuttering schools and claiming girls as brides. It’s as if the last 20 years never happened. Except it’s worse. Because the girls and women of Afghanistan had a taste of normalcy, of a life with purpose, of a future without the shackles of fear and oppression. I fear that’s all gone. The images on my TV fill me with dread, horror, and incredible sadness. Yet, I will watch the developments from afar and hope for the people who let me capture their initial taste of freedom.

---

Bita Honarvar is an Atlanta-based photographer who specializes in storytelling photography. She worked for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution for 16 years, where she was a staff photojournalist and photo editor. She currently works part-time as a photo editor with the AJC. Her work has taken her around the United States and abroad, including stints in Afghanistan, Iraq and Iran, but believes you can find compelling images and engaging stories just about anywhere if you keep your eyes, ears and mind open.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured