This story was originally published in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution on Aug. 24, 2004.

The state plans to move 1 million low-income Georgians on Medicaid into HMO-like organizations --- a cost-cutting tactic representing one of the biggest changes in the government program's history.

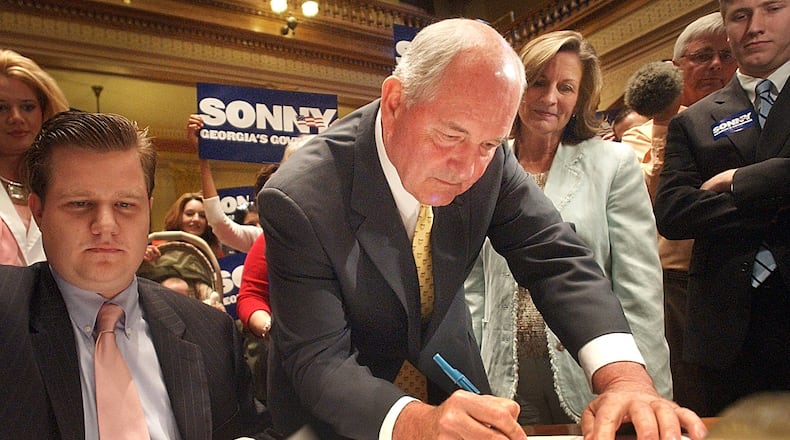

The plan, unveiled Monday, is being pushed by Gov. Sonny Perdue as a response to spending increases of 10 percent to 12 percent a year in Georgia Medicaid.

The change is necessary "because we cannot sustain the program in its current form, " Perdue said.

Some experts say converting 1 million people enrolled in Medicaid to HMOs may cause problems for patients.

Currently, these Medicaid recipients are in a fee-for-service system, where they can go to any doctor who accepts Medicaid patients.

The more restrictive, managed-care plan proposed by Perdue is expected to begin in January 2006. But other major changes in Medicaid may come sooner.

On Wednesday, the board of the state Department of Community Health is expected to consider a new round of cuts for the next fiscal year. Medicaid cuts this year caused an uproar among patient advocates, who criticized restrictions placed on eligibility for pregnant women, among other changes.

State officials, however, forecast that Medicaid will eat up 43 percent of all new state revenue in the current fiscal year --- a figure that, if unchecked, will reach 60 percent by 2011.

Jointly financed by the federal government and the state, Medicaid provides health coverage for 1.4 million low-income Georgians.

Plan affects 1 million

The switch to HMOs would affect about 1 million children, pregnant women and adults in low-income families in Georgia. This group represents about 40 percent of the cost of the state's Medicaid program, or about $2.2 billion annually in federal and state funds.

People in long-term care, such as in nursing homes, and those classified as "aged, blind and disabled" --- who account for about 60 percent of Medicaid costs --- won't be affected by the proposed change.

"We're not aware of another state that has gone this far all at once, " said Tim Burgess, commissioner of the Georgia Department of Community Health, which operates Medicaid. "We want to create a very Georgia approach to this and a very Georgia solution."

Experts say Arizona, Tennessee and California have similar programs. And the trend toward HMOs for Medicaid patients may increase as states look to cut costs, said David Rousseau, a senior policy analyst of the Kaiser Family Foundation in Washington.

Prior effort unpopular

Georgia had a voluntary HMO program in the 1990s for Medicaid, but the effort proved unsuccessful at attracting a large number of people willing to enroll.

State officials said Monday the 203,000 children in the PeachCare program for uninsured children will be put into the managed-care organizations.

But state Rep. Mickey Channell (D-Greensboro), an architect of PeachCare, said the Legislature would have to approve such a change. Under present law, any managed-care option in PeachCare must be voluntary, he said.

The overall Medicaid change to HMOs apparently doesn't require specific enabling legislation, but must go through the budgeting process in the General Assembly.

State officials said the alternative is more budget cuts. Such cuts this year included higher premiums for PeachCare, a plan to recover long-term care costs from Medicaid beneficiaries' estates and a halt to a "medically needy" program for nursing home residents who earn too much for Medicaid but not enough to afford private care.

Burgess, the state Community Health commissioner, said that besides cutting costs, the HMO setup would aim to improve the health of affected patients through such measures as increased child immunizations and well-child visits. "We're going to try to ensure [patients] go to a physician, instead of showing up in an emergency room, " he said.

6 regions designated

The state would be divided into six regions, and each would have two managed-care organizations for patients to choose from. The HMO-like groups would offer current Medicaid benefits, but could add new services, such as special prevention programs to combat chronic diseases, including diabetes.

State officials, who said HMO care would be monitored, said patients won't necessarily be forced to give up their physicians. But some members of the medical community expressed concerns.

"Often, HMOs require referrals [for patients] to see specialists, " said Jaye Peabody, executive director of Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies Coalition of Georgia, which seeks to improve access to health care. "If a woman has a high-risk pregnancy, will it be a problem for her to see a specialist?"

Dr. Fred Gober, an obstetrician, said if physicians and others who traditionally treat Medicaid patients are not included in the HMOs, patients could feel dislocation and have transportation problems in traveling to a new doctor.

Another possible downside is the confusion caused by such a major overhaul, said Leighton Ku of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington.

While states can save money initially through Medicaid managed care, Ku said, "What is less clear is whether they can sustain savings long term."

Rep. Channell, while commending the goals of the initiative, said, "The state of Georgia overall delivers Medicaid services in a very cost-efficient way now."

Among Southeastern states, Georgia is second lowest in per-recipient Medicaid spending, Channell said. "There has to be a very, very large public debate to this, " he said. "A lot of potential problems have to be addressed."

State Sen. Tommie Williams (R-Lyons) said managed care is necessary.

"It's addressing a crisis we're having in funding Medicaid, " he said. "What we're doing now, nobody is really happy with."

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured