The administration of President Donald Trump has opened the door to imposing work requirements on Medicaid recipients. And some Georgia leaders are interested.

Each state sets its own specifics, but the broad principles for Medicaid eligibility have long been the same. For a half-century, Medicaid has guaranteed health coverage to poor Americans if they make little enough money and meet the right family and health circumstances.

This would change that.

The change announced Thursday would apply to comparatively few Georgia Medicaid recipients, but it unleashed deeply held feelings among Georgians about what health care for the poor should do and what, if anything, the government and fellow citizens owe each other.

"I don't think anybody is entitled to spend taxpayers' dollars without working for them or reimbursing them," said state Rep. Greg Morris, R-Vidalia, who successfully pushed a bill that required drug tests to get food stamps. "I appreciate the Trump administration's giving that option to the states."

On the other side, Dr. Karen Kinsell, who is the only doctor in Clay County and runs a clinic for the poor, said she would have trouble repeating her reaction to the directive. “I’m supposed to answer in a way that is printable, right?” she asked.

“We don’t have a work requirement, before you call the police,” she said. “If you read the Declaration of Independence — it is a right to ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.’ People have a right to basic things that allow them to live.”

Seema Verma, who led the charge for the change as Trump’s administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, framed the change as a health issue. She has to, since legally, any eligibility requirement changes must advance the goal of the Medicaid program. For that reason, critics say the change will quickly wind up challenged in court.

Verma, in her announcement, said that work leads to health, noting that unemployment is linked to depression and that wealthier people live longer than poorer ones. Opponents say, though, that none of the studies linking physical health and work show that work itself causes the people to be healthier. They say it may be the other way around.

“It’s much more likely that people that are already healthy are more likely to be working,” said Laura Colbert, the director of Georgians for a Healthy Future.

The administration’s guidance was designed to give states the freedom to develop their own programs. It targets working-age adults who are not pregnant and not disabled. It does not presume every recipient would have a job, but that they would at least be working toward a job or community service, which it termed types of “community engagement.”

Georgia’s Medicaid program would not be upended by a work requirement, since the state already gives Medicaid to very few working-age, able-bodied adults. In Georgia, Medicaid tends to cover children, the disabled, some elderly people, pregnant women and very low-income parents. The very low-income parents — making $653 per month or less for a family of four — would seem to be the ones in the cross hairs of the new policy, and there are just perhaps a few thousand of those, Colbert said.

The state Department of Community Health said it could not immediately say precisely how many would be affected. It is “reviewing” the guidance, spokeswoman Fiona Roberts said.

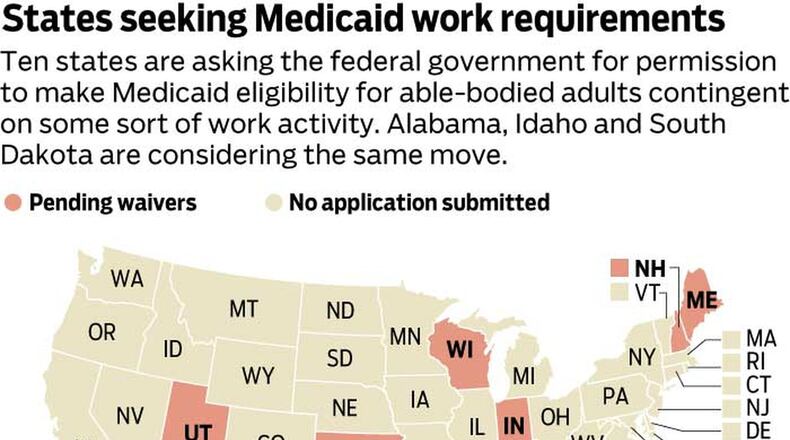

Ten states are ready to go with such requirements, and the administration may start approving them soon. They are types of pilot projects, and they don’t require passage by a state Legislature. But in Georgia, the governor’s office has often gone through the Legislature before proposing such changes. A spokeswoman for Gov. Nathan Deal also said his office was reviewing the guidance.

The chairwomen of Georgia's legislative health committees, state Rep. Sharon Cooper, R-Marietta, and state Sen. Renee Unterman, R-Buford, each said they supported the principle of a work requirement, though the devil was in the details.

“I think most able-bodied human beings would like to be productive and have a job,” Cooper said. However, she would find it important that the state also have programs to connect the people to the work.

Unterman also said hiring professional screeners would be important so that people who deserve coverage would not be wrongly denied. “I do think it would be cost-effective,” she said. “And it sends a good message. … The economy is booming. People who can get a job should get out and get a job.”

Morris forcefully echoed that sentiment. He acknowledged something offensive about an “able-bodied” person being on Medicaid without working. “A desperately ill individual” should not be penalized for not working, he said, but for others, medical care was not a basic right the state must provide.

“I would just ask them to show me in the Constitution in the United States or state of Georgia where that is a right,” Morris said. “I haven’t read that.”

Advocates such as Kinsell said there were other reasons to avoid a work mandate. She says that in her county there are not jobs for unskilled people with no transportation. She also fears the destructive insertion of more bureaucracy, as she has seen in her practice.

When people are disabled from an orthopedic injury, she said, even though surgery can often fix the problem, it takes years of red tape to get them declared disabled and eligible for surgery funding. They settle in the rut of being disabled.

“The chances of actually getting back to work after all that has happened is pretty low,” she said. “That’s a true economic damage.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured