Heeding calls to "drain the swamp," President-elect Donald Trump is requiring appointees to his administration to agree to a five-year ban on lobbying, a nod to the public's distrust of the revolving door that allows former politicians to press their peers for legislative favors.

In Georgia, the ban is one year for elected state officials and some appointees. But it doesn’t stop big firms with deep pockets who want to snap up retiring politicians while they still have plenty of friends under the Gold Dome.

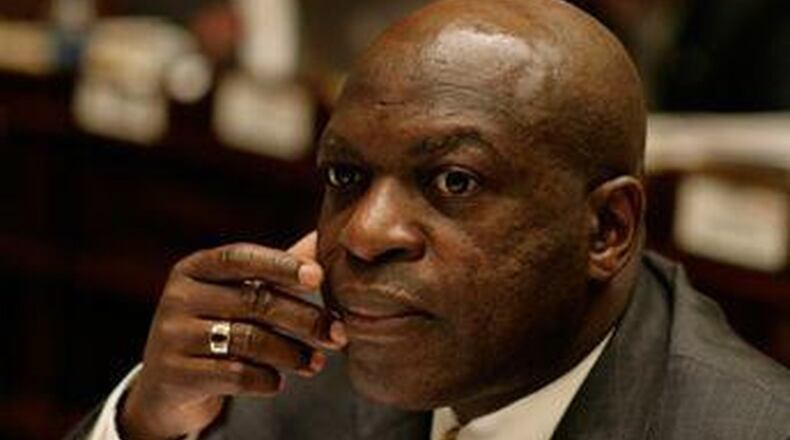

Virgil Fludd is a the latest example. Fludd served seven terms in the State House, rising to chair the Democratic Caucus and serving on the Banking, Regulated Industries and Ways and Means committees.

Fludd announced earlier this year that he would not seek re-election to his House seat, where he represented Tyrone and its surroundings. In fact, he didn't even serve out his final term, opting for early retirement a month ago to take a plumb job as senior advisor for public policy and regulation at Dentons, an international law firm with a large lobbying practice.

Fludd can’t register to lobby his former colleagues until next November, but that didn’t stop Dentons from touting his influence to possible clients.

“His focus is on Georgia government affairs, at the local and state levels, for clients across a range of sectors,” according to his executive bio on Dentons’ website.

If Fludd can’t lobby for these clients he is supposedly focusing on, what will he do for them?

Dentons’ bio of Fludd continues: “He has particular experience representing the highly regulated financial technology industry and the film and television industry. He also has extensive experience advocating for clients regarding tax-related legislation and regulations.”

Wait, what?

He's represented clients in regulated industries and advocated for them on tax legislation? I thought he was representing us when he served on those legislative committees.

Eric Tanenblatt, Gov. Sonny Perdue's former chief of staff who now heads up Dentons' North American lobbying shop, said the wording in the bio was put there in error. "It's being corrected now," he told me.

Obviously Fludd hasn’t represented clients in such a manner. He’s forbidden from lobbying for a year, and Tanenblatt said the firm takes that cooling-off period seriously.

“We are very careful about that. We have 120 people in our public policy group across the United States,” he said. Each state has its own rules about when a former legislator can start lobbying his or her peers.

In Colorado, for example, former public officials have a two-year waiting period before they can begin lobbying. That didn't stop Dentons last year from hiring Amy Stephens, the former House majority leader.

Stephens heads the firm’s lobbying practice in Denver despite having more than a year left to cool off.

In an interview, Fludd told me he would be “providing advice and strategy” to Dentons’ lobbying practice and concentrating on “business development work” for the coming year.

That means Dentons expects Fludd’s legislative background to be useful in recruiting new clients. In the coming year, he can use his well of knowledge to help those clients and Dentons’ stable of registered lobbyists get what they need from government.

“Obviously we would tap into their knowledge of the Legislature,” Tanenblatt said of Dentons’ hiring of former lawmakers like Fludd.

Close ties fuel voter distrust

To some, that may sound like lobbying from a distance. But Fludd, who also served on the House Ethics Committee, said he is well within the law.

“I support the idea of a one-year cooling off that limits former legislators access to the executive branch and former colleagues,” he said.

To Fludd, lobbying means having direct contact with former lawmakers, rather than merely advising those who do. That’s how his boss sees it too.

Fludd, Tanenblatt said, has recent experience with the legislative process and should be allowed to share that with a new employer.

“I don’t think you can prevent people from using their knowledge base,” he said. “What crosses the line is interacting with government officials.”

That’s how the state law has traditionally been interpreted. That doesn’t mean they don’t meet them for dinner or play a round of golf with them, but as long as they don’t talk about their clients they are “cooling off.”

But if national public opinion polls are to be trusted, the close ties between lobbyists and lawmakers are part of what fuels voter distrust. A Gallup poll conducted this summer found that a majority of Americans who gave Congress a failing grade believed that legislators pay too much attention to lobbyists and special interests.

That’s a national look, but in 2012 huge majorities of voters in the Democratic and Republican primaries backed limiting what lobbyists could spend on state lawmakers, so there’s distrust at home too.

Lawmakers to lobbyists

While Dentons and Fludd are the latest marriage of note, they aren’t alone. The path from the Capitol to lobbying firms is well worn.

In 2015, former House Appropriations Chairman Ben Harbin resigned his office and went to work for Southern Strategies Group and its team of lobbyists.

Senate Republican Leader Ronnie Chance decided in 2014 not to run for re-election. By February 2015, Chance had taken a spot with the Hudson Group as "senior advisor and consultant."

Former House Speaker Pro Tem Mark Burkhalter, who briefly became House speaker in December 2009 following Speaker Glenn Richardson's personal meltdown, announced his retirement during the 2010 legislative session. Less than a month later, he took a job with McKenna Long & Aldridge. McKenna Long merged with Dentons last year and Burkhalter remains there as — stop me if you've heard this one — a "senior advisor."

Burkhalter is not a registered lobbyist and can’t register legally because he currently sits on the State Transportation Board. Appointees to state boards cannot be registered lobbyists.

While other former lawmakers find landing pads in lobbying firms around town, few ponds are as well stocked as Dentons. Dentons’ government affairs practice includes former U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich, former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean, and Buddy Darden, a former Georgia congressman, among other legislators, ambassadors and sundry ex-officials.

And this summer, Ed Lindsey, former Republican whip in the Georgia House, joined Dentons two years after his congressional bid ended in a primary defeat.

With such a deep pool of talent, Fludd said he expects to spend the next year learning the ropes. Will he join the ranks of registered lobbyists when the cooling off period ends next November?

“I don’t know yet,” he said. “Mostly likely I will, but that is a year away.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured