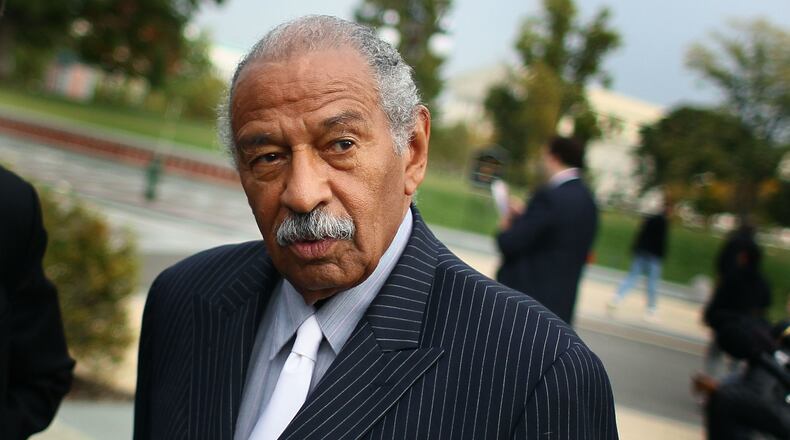

Democrat John Conyers, the longest-serving African American legislator in congressional history who was a leading voice on civil and voting rights issues, died over the weekend at the age of 90.

The #MeToo movement tarnished Conyers’ legacy – he stepped down in 2017 as sexual harassment allegations swirled, even though he denied wrongdoing – but the Michigander was a giant on Capitol Hill and a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus, the influential group that counts all five of Georgia’s Democratic lawmakers as members.

One of Conyers’ crowning achievements came 36 years ago this week, when President Ronald Reagan signed legislation creating a national holiday honoring Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday.

The holiday, celebrated the third Monday in January, is nothing if not an example of political persistence.

Conyers first introduced the legislation four days after the Atlanta civil rights leader was assassinated in April 1968, but it still took 15 years of behind-the-scenes maneuvering to get the measure through both chambers of Congress. Every time the bill was considered in the intervening years, it was voted down or never made it to the floor.

Conyers enlisted the CBC to help make the push – the group eventually collected millions of signatures in support – and Stevie Wonder penned a song about King’s birthday that helped raise public awareness. An Atlanta Constitution article published Oct. 20, 1983 detailed broader factors that led to the bill’s eventual passage:

In the late 1970s, however, support in Congress for a King holiday gradually increased as the power of the black vote began to influence elections. Then, President Reagan's economic policies brought charges that he and Republicans in Congress were insensitive to the issues confronting black Americans. Those charges persuaded a number of Republicans in the House to vote for the King holiday.

Conyers, who worked with King before coming to Congress in 1964, told The Washington Post in 2015 that the Nobel prize winner “is the outstanding international leader of the 20th century without ever holding office”

“What he did — I doubt anyone else could have done,” he told the newspaper.

The final showdown played out in the Senate in the fall of 1983.

Reagan had dropped his opposition to the bill – he was initially resistant to granting federal workers an additional paid holiday but said later that “the symbolism of that day is important enough that I will sign that legislation when it reaches my desk.”

After the measure cruised through the House 338 to 90, U.S. Sen. Jesse Helms, a fierce critic of the Civil Rights Act, waged a 16-day filibuster against the legislation.

Helms, R-N.C., said creating a new holiday would cost the economy billions a year. He charged that King had associated with communists and pressed the FBI to release sealed documents created to undermine him.

Georgia’s two U.S. senators, Sam Nunn and Mack Mattingly, unsuccessfully pushed for an amendment that called for the holiday to be observed on King’s actual birthday of January 15, arguing it would save the government money. Both ultimately supported the legislation.

As lawmakers cast their final votes, King’s widow Coretta Scott King looked on from a visitor’s gallery overlooking the Senate floor.

It’s a “great day . . . to those of us who believed in the dream,” she later told reporters, according to the Atlanta Constitution. “It's a great day for Americans and the world. We're proud to be Americans, but I think today we're even prouder.''

Read more: John Conyers, longest serving black congressman, dies at 90

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured