Though Democrats are threatening Republican control of the Georgia House, legislative leaders say there’s not much chance of passing a bill that would take the redistricting process from the hands of whichever political party is in power after the 2020 elections.

Republicans believe they'll retain their tightening majority in next year's elections, giving them the ability to draw districts that further entrench themselves when the General Assembly redistricts the state in 2021. Democrats acknowledge that their proposal for an independent, nonpartisan redistricting panel won't move forward without Republican support.

The impasse over redistricting raises the stakes for elections in November 2020, when Republicans will attempt to fend off Democrats’ attempts to pick up the 16 seats they’d need to become the majority in the House. Republicans held a 105-75 advantage this year.

Every 10 years, each state must redraw state and congressional district lines to account for population shifts. That process will take place after the 2020 census.

In most states, including Georgia, politicians draw their own maps, allowing them to tailor district boundaries that include more of their voters, helping ensure their re-election. Some states have shifted the redistricting task to independent or bipartisan commissions to reduce partisan gerrymandering.

Just over half of Georgia voters supported Republican Brian Kemp in last year’s statewide election for governor, but Republicans control larger majorities in the districts they drew nearly a decade ago — 59% of the General Assembly and nine of the state’s 14 seats in the U.S. House.

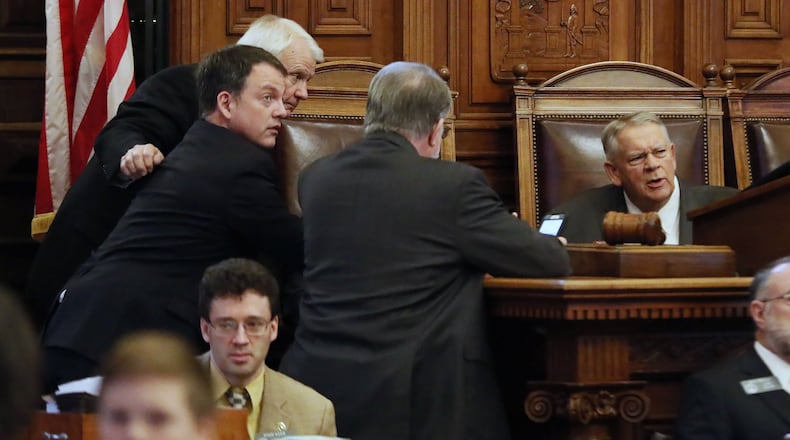

Republican state House Speaker David Ralston said Democrats only sought nonpartisan redistricting after they lost all power in 2005.

“I get why they put it forward now because they know that maybe gives them something they don’t have because they can’t win elections,” said Ralston, who represents Blue Ridge. “I can’t get any member of the minority party to tell you why it’s a good idea now but it wasn’t a good idea when they were in the majority.”

Democratic state House Minority Leader Bob Trammell acknowledged it would be "a heavy lift" to persuade enough Republicans to support an independent redistricting commission.

“When the maps were drawn, they were drawn to have very few competitive districts,” said Trammell, who represents Luthersville. “As a practical matter, I don’t know that our Republican colleagues see the (redistricting) proposal as something they’re willing to move forward in the 2020 session, but hope springs eternal.”

Democratic legislators introduced measures in the state House and Senate this year for an amendment to the Georgia Constitution creating an independent redistricting body made up of citizens representing both major political parties, as well as Georgians who aren't identified with a political party. Neither of those proposals, Senate Resolution 52 and House Resolution 369, received a hearing. They would need two-thirds majorities in both legislative chambers to pass next year.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled last month that electoral maps should be decided by voters and elected officials, not by federal courts. But the court's ruling left in place the ability for states to pass legislation to create nonpartisan commissions to redraw district lines.

When Republicans were gaining on Democrats in the 1990s and 2000s, majority Democrats paid more attention to redistricting, said Keith Mason, who was chief of staff for Democratic Gov. Zell Miller during the 1990s. Now Republicans are doing the same thing.

“Generally speaking, the dominant party tries to control as long as they can,” Mason said. “The closer it gets, the more bipartisan it might become. You might see a little more bipartisan cooperation out of incumbent self-preservation.”

The creation of independent redistricting panels usually only happens as a result of a citizen initiative process to put the issue on the ballot, said Yurij Rudensky, who focuses on redistricting issues for the Brennan Center for Justice, a policy institute at New York University.

Georgia doesn’t allow citizen-driven initiatives. Changes to state laws must originate with the General Assembly.

But in some states that are closely split between Democrats and Republicans, such as New Hampshire and Virginia, legislators passed bills this year to hand off redistricting to citizens, Rudensky said.

“You really do see people wanting to make government a little more functional,” he said. “You see some of these states where people say, ‘We don’t want to go through that again.’ That mess can be so polarizing and debilitating.”

Stay on top of what’s happening in Georgia government and politics at www.ajc.com/politics.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured