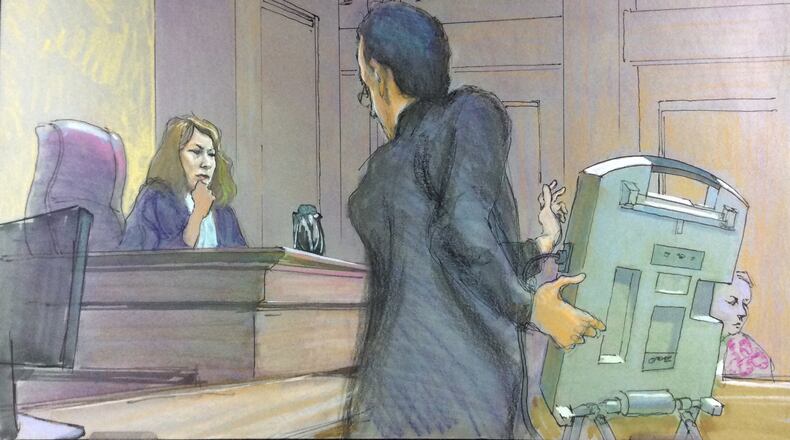

A federal judge who is deciding whether to shut down Georgia’s 27,000 electronic voting machines heard testimony Thursday that they flipped votes, lost ballots and posed election security risks.

A packed courtroom listened as U.S. District Judge Amy Totenberg considered a request that she immediately put the state’s 17-year-old voting machines out of service for this fall’s local elections, which include votes for the Atlanta school board, the Fulton County Commission and city councils across the state.

State officials are already preparing to announce a replacement voting system that would go into use statewide in the March 24 presidential primary.

But the concerned voters and election integrity advocates who sued say Georgia's existing voting machines are fundamentally insecure and susceptible to hacking. They also plan to challenge the state's incoming voting machines, which will still use touchscreens but with the added component of printed-out ballots that create a backup of electronic vote counts. The plaintiffs want voters to use paper ballots filled out with a pen.

Totenberg didn't signal how she would rule, but she said last fall that Georgia's direct-recording electronic voting machines create a "concrete risk," and election officials "had buried their heads in the sand" about vulnerabilities. At the time, she declined to disqualify the state's voting machines just weeks before November's high-turnout election for governor.

Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger has said that Georgia’s voting machines are safe, and there’s no evidence they’ve been tampered with. But tech experts have testified that malware could be written so that it’s undetectable.

In court Thursday, the judge heard from voters and state election officials as attorneys for the plaintiffs pointed out problems with Georgia’s voting machines and voter registration system.

One voter, Teri Adams, said her voting machine in Bleckley County repeatedly changed her vote in the governor's race from Democrat Stacey Abrams to Republican Brian Kemp.

When she first reviewed her ballot on the touchscreen, it showed she had selected Kemp, she said. Before casting her ballot, she started over, but again the voting machine showed she had picked Kemp. Only on her third try did the machine display her vote correctly.

“It changed my vote,” Adams said. “I went to verify it again, and it changed back.”

Attorneys for the plaintiffs also questioned whether voters' information was secure after it was left available for download from a state election server housed at Kennesaw State University in 2016.

In addition, they entered into evidence documents from a cybersecurity company hired by the Secretary of State’s Office that identified 22 risks in 2017 and 15 risks in 2018. The cybersecurity company was able to penetrate the Secretary of State's network in 2017 and 2018, obtaining administrator rights and system configurations.

Those potential vulnerabilities have been addressed, said Merritt Beaver, the chief information officer for the Secretary of State’s Office. The full list of risks hasn’t been released.

“I feel confident in Georgia’s elections system,” said Michael Barnes, the director of the state’s Center for Elections Systems, which creates ballots and distributes them.

Totenberg could rule anytime after the two-day hearing concludes Friday.

Stay on top of what’s happening in Georgia government and politics at www.ajc.com/politics.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured