He reveled in the nickname.

The Hammer.

A share-cropper’s son turned millionaire Augusta businessman, Charles Walker rose to become the Georgia Senate’s first African-American majority leader. He had the power to make sure most anything he wanted for his community made it into the state budget — and the political muscle to get things done at the Capitol.

When the feds came after him, they came hard, and he was convicted on mail fraud and other charges and sentenced to a decade in prison. His political career seemingly over, he spent much of his time behind bars unsuccessfully fighting his conviction.

And taking notes.

“When I was in captivity, I had a chance to think. What kept me occupied, what kept my sanity, was focusing on Charles Walker,” he said in an interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “Where I have been, where I have come from and how I was going to fight my way out of this trap.”

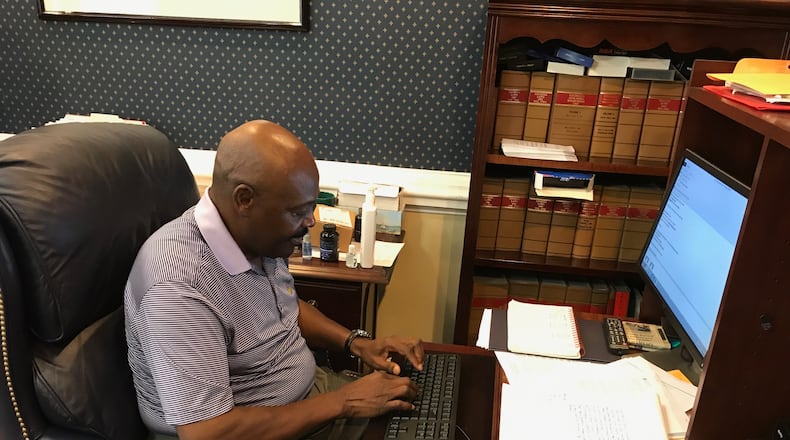

Three years after his release from federal prison in Estill, S.C., he’s written one book about his experiences, “From Peanuts to Power,” and is working on a second. It will focus on Georgia politics since the 1970s, leadership and grass-roots political activism, which he said is as needed as ever today.

Walker has continued to be involved in the political and business scene in Augusta, albeit more behind the scenes. Three of his four children are lawyers, and his kids run his businesses. He’s stayed away from the state Capitol, where he made his name and which some thought he could eventually run.

His is a tale of a poor kid making good, a rise to power and a fall that was the talk of the statehouse — and Augusta — a little more than a decade ago.

Georgians new to the state only know Capitol politics as a one-party game, and the players are mostly Republican.

But 15 years ago Democrats dominated the state and had since Reconstruction. At the time, in 2002, Roy Barnes was a powerful governor in a state with a history of powerful governors, and Walker was both his friend and his right-hand man in the Georgia Senate.

Walker was a larger-than-life figure: imposing to some, charming to most, and in possession of a deep understanding of politics. He knew how to get support for his cause. He was also a voracious fundraiser, a firm believer that politics can be cruel to the penniless.

“He was a skilled political animal, and I say that in both getting elected and getting things accomplished,” said Eric Johnson, a Savannah Republican who served as minority leader in the Senate at the time and often clashed with Walker in policy debates.

Some said a political feud between Walker and then-Democratic Senate President Pro Tem Sonny Perdue led to the latter switching parties and eventually becoming the state’s first GOP governor.

Like many top politicians of the age, there were rumors that federal investigators were looking into Walker and other leading Democrats.

“I think what got Charles into trouble was he couldn’t separate his political interests and his business interests,” Johnson said. “There was always a feeling that there was a Charles Walker Inc. side to him that probably hurt him.”

Walker, like Barnes, House Speaker Tom Murphy and some other Democrats, was swept from office in the 2002 elections. But Walker won back a Senate seat two years later, despite the fact that the federal government had filed a 142-count indictment against him, with charges including mail fraud, income tax evasion and conspiracy.

Walker was one of three prominent Augusta-area politicians indicted during a relatively short period of time, along with former state Rep. Robin Williams and ex-Georgia School Superintendent Linda Schrenko — both Republicans. All three went to prison.

Walker was convicted in 2005 of stealing from the charity he set up, of bilking advertisers in a newspaper he owned, of strong-arming Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital into using his personnel services business, and of misrepresenting his ownership in companies doing business with the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta.

Prosecutors argued that at least part of the reason Walker needed the money was to support a $2,400-a-hand blackjack habit. Walker said the charges were bogus and an example of selective prosecution by a Republican-led federal government bent on silencing him. A jury convicted him of most of the counts after a two-week trial.

Walker’s daughter was originally accused of some of the same crimes as her father, but she pleaded guilty a month after his trial to a misdemeanor count of filing a false tax return and was sentenced to probation.

He begins “From Peanuts to Power” describing the loneliness of his time in prison. He describes the sameness of his days, starting each eating a bowl of oatmeal, reading newspapers to keep up with the world, and walking the track around the facility over and over.

“I walk the track, repeating to myself that I am one day going to beat the sons of bitches,” he writes. “I think of my wife and children. I worry about the silent burden that I have placed on them. I worry about the embarrassment that I have left them to deal with. All the broken promises. The missed graduations. I carry a heavy burden; my family is my major focus.

“I have long forgotten the political relationships and the fair-weather friends. I think now only of the people that really matter.”

Walker said he spent five years fighting his case in the courts, but his appeals failed and he remained behind bars. He served about eight years in prison before being released to a halfway house and home confinement.

The former power broker, now 69, said while he’s always believed in his innocence, he wasn’t bitter.

“I didn’t have time for bitterness because being bitter consumes too much time and you can’t allow the system to occupy that much time in your head,” he said. “You’ve got to do positive things. I had to advise my children about running the company.”

The Rev. Kenneth Walker — no relation — is now senior pastor/organizer at Greater Elizabeth Bible Church in Atlanta, but he was the senator’s longtime top aide, and he remains close to him. He said the former lawmaker is in many ways the same man he was before he went to prison, maybe better.

“Our experiences have the capacity to make us better or bitter,” Kenneth Walker said. “Charles Walker chose better when he could have opted for bitter.”

He almost didn’t have the chance to go for “better.” A few months after being released from prison, Walker was on his way to Columbia, S.C., when traffic slowed near an overturned truck. He slowed, too, but he said a tractor-trailer came over a hill and slammed into his vehicle. His car flipped and he suffered a serious concussion and subdural hematoma that required surgery.

He recovered, and a year later he released his first book. Walker said he has sold about 7,000 copies, some at a book-signing event hosted by Barnes. His second book doesn’t yet have a title.

Walker said he tries to play golf a few times a week, works real estate deals, donates to local candidates and regularly speaks in the Augusta area. He looks fitter and more relaxed than he did before he went to prison.

He stays abreast of what’s going on in local and national politics, but he finds state politics a bit bland. He spent much of Barack Obama’s presidency in prison, and within a little more than a year of his release, the politician on everyone’s mind was Donald Trump.

While he considers the president a “first-class” B.S. artist, he added: “What I admire about him, more than anything is, he’s … got guts. I understand his politics, and he works it as well as anybody in my lifetime.”

Walker said when he goes to restaurants in Augusta now, people often come up to talk to him.

“My place in society has not been removed,” Walker said. “People believe in justice, people believe in fairness, and most people believe I got screwed.”

He has little desire to travel to Atlanta, where he made a name for himself, where some once talked of him becoming Georgia’s first black governor or lieutenant governor.

“I still have a condo there. I was up there a month ago to see ‘Phantom of the Opera,’ ” he said. “I love Broadway plays. I want to see ‘Hamilton,’ so I am going to go to New York to see it.

“People say you can’t get tickets,” he added with a smile. “But I can.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured