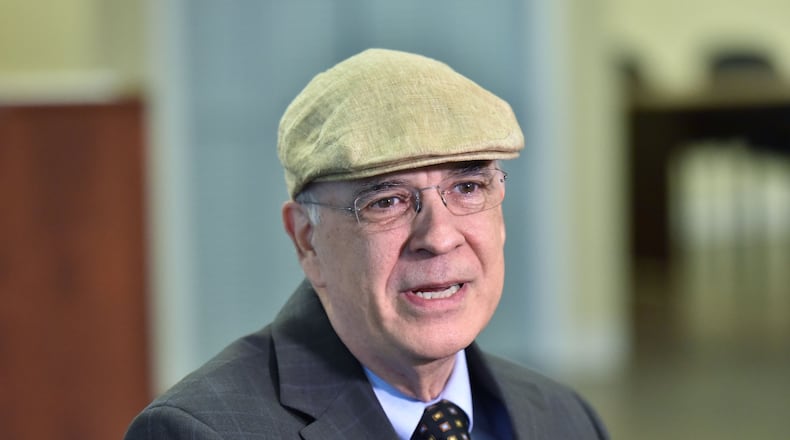

Jim Barksdale, Democratic candidate for U.S. Senate

Age: 63

Residence: Atlanta

Profession: Founder of Equity Investment Corp., an investment firm with a roughly $5 billion portfolio, according to his campaign.

Previous experience: No prior elected political experience. Before starting his investment firm in 1986, he held corporate jobs in the U.S. and Europe at Management Asset Corp., Merrill Lynch and IC Industries.

Education: Bachelor of Science degree in psychology from the College of William and Mary, 1975; Master of Business Administration from the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, 1977.

Political strengths: An outsider in an anti-Washington election year, Barksdale's lack of political credentials likely work to his advantage, especially when juxtaposed with the incumbent, Johnny Isakson, who is essentially the definition of the Republican establishment in Georgia. At the heart of Barksdale's platform is income inequality and putting a tighter leash on Wall Street regulation, two issues that have animated Democratic voters this cycle. His willingness to reach deep into his own pockets to fund his campaign is useful against an incumbent with more than $5.7 million in the bank.

Political liabilities: Barksdale was late to build a campaign infrastructure and public presence, and he is still largely an unknown to many Georgia voters. New to politics, he lacks the breezy charm of a seasoned politician and can be awkward in public. Until recently he has shied away from capitalizing off GOP divisions over Donald Trump by tying Isakson to the polarizing Republican nominee, and his Bernie Sanders-like message may not gel with Georgia Democrats, who overwhelmingly went for Hillary Clinton in the March primary.

Notable endorsements: Democratic U.S. Rep. Hank Johnson, Georgia House Minority Leader Stacey Abrams, former Atlanta Mayor Shirley Frankin

Family: Divorced; two adult children.

It took a while for Democrat Jim Barksdale to find his footing as a U.S. Senate candidate.

But after a summer of fits and starts — including a full-scale staff shake-up — Barksdale plunged into autumn with a decidedly Bernie Sanders-style message that he thinks will carry him to victory in November.

His top issues: Looser campaign finance regulations have built a political system that favors big business and wealthy donors. Bad trade deals have aided multinational corporations while hurting American workers, who have also been damaged by the deregulation of Wall Street.

“I think (people) really respond to a sense that Washington is broken and that they know something is wrong, that their voice is not being heard and they know that the money in politics has robbed them of their voice,” Barksdale said in a recent interview.

But Barksdale differs from Sanders in a key respect: He himself is a multimillionaire. Instead of relying on small-ball donations of less than $50 and grass-roots inertia, the investment manager has poured millions of his own personal fortune into the race while doing very little fundraising.

Barksdale was a political unknown when he threw his hat into the ring to challenge Republican incumbent Johnny Isakson in March after a string of better-known Democrats passed on the chance.

Barksdale’s campaign got off to a bumpy start. The Atlanta resident said he’d never really spoken publicly before qualifying in March, and it took him months to begin campaign appearances or media interviews.

“It’s come a long way,” Barksdale said of his campaign in September.

From the beginning, though, Barksdale made a slightly frumpy touring cap central to his campaign, a signature item meant to symbolize his outsider status and desire to shake up the status quo.

Barksdale thinks that populist-spiked, anti-establishment rhetoric, particularly on trade, will help him appeal to Donald Trump supporters fed up with Washington.

In his first attack ad, he accused Isakson of voting “for every bad foreign trade deal since he got to Washington.”

Barksdale’s biggest challenge was and continues to be name recognition. Isakson has plenty more of it after decades in Georgia politics, and until recently Barksdale spent relatively little on television ads to get his name out.

But time is running short, and Barksdale entered October trailing badly behind Isakson in the polls.

His new staff, filled with alums from the Sanders campaign, have ground to make up, particularly as they look to appeal to the young people who once were attracted to their former boss and have become tempted by Libertarian candidates.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured