Torpy at Large: How our youngest, who died, led us as he left us

Michael opened his eyes with a glint of delirium not uncommon overnight in the Neuro ICU.

For more than two years, our youngest had battled osteosarcoma, an aggressive bone cancer. But in March, the oncologist leveled us with devastating news — the disease had metastasized to his spine and several vital organs.

Time was short, so Michael, an Eagle Scout and avid backpacker, visited his sister in Denver recently to experience the great outdoors one more time.

While there, he grew weak and disoriented. The cancer had invaded his brain. We had always feared such a development. Now it was an inescapable reality.

“There’s no satisfying end to this, for anyone,” he said, looking at me, in a sleep-deprived, drug-induced, brain-swollen daze. “There’s no good end.”

He continued: “Thank you, you’re a good author and thanks for the experience. There were some good characters in this.”

Then he added: “Give me a hug. You don’t deserve this.”

The next day we got him back to Atlanta, where he was able to die in his home six days later. He was 20.

To his comment that I didn't deserve this? What?!?

I wasn’t the high school senior diagnosed in April 2017 with cancer in his thighbone. I didn’t spend nearly 100 nights in a hospital enduring continued doses of industrial-strength chemo. I didn’t have my knee and two-thirds of my thighbone sawed off and replaced by titanium, or later endure a massive chest surgery, one that provided fleeting hope of a cure.

In December 2017, a crowd of doctors, nurses and aides stood in the lobby and cheered goodbye as we walked from the oncology unit at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston.

But the cancer came back. Quickly. And then back again. And again.

SEPTEMBER 2017 | Torpy at Large: The wolf comes to the door when your kid gets cancer

FEBRUARY 2017 | Torpy at Large: A brother gone, a hard hole to repair

He got experimental chemo treatments, lifted weights, and ate what he could keep down to regain the strength and weight that he’d lost. Though often nauseous, he trudged onward. Head down, eyes forward.

Last summer, he tangled with one of his old wrestling coaches in our family room and separated his shoulder as they hit the floor — the coach’s shoulder, not his own.

After 15 months of treatments and operations and recovery, Michael finally was cleared to attend the University of Georgia. But in August, as he went off to UGA, a CT scan showed the cancer was growing again.

Minutes after getting the news, he was walking to his car to return to Athens. I was devastated, doing the quivering stiff-upper-lip routine.

Then, Michael turned back and said, “Dad, leave me with a smile.” His own smile made it so I could do nothing but.

Again, his emotions came second. He hated talking about his cancer. He didn’t want it to define him, didn’t want his mom to cry. I don’t think he ever told his dorm-mate he had cancer.

But it hung there, unsaid. And he reckoned with mortality long before one should. Once, he asked his mom — my wife, Julie — “Have I lived a full life?”

Yes, she said, citing his accomplishments, travels and life experiences. He lived a full life. He just wasn't accorded a long life. No one's guaranteed the 80-year card.

He was able to make it at UGA until March, waking up, dragging himself from bed, downing his chemo, throwing up, then heading to class. The experience gave him some well-deserved freedom and time to run with friends, as evidenced by fake IDs in his wallet.

Michael did, however, get straight A’s and was named a Presidential Scholar. When he heard me bragging on that, he shrugged and said, “Presidential doesn’t mean what it used to.”

He’d be peeved at me for going on so much about his cancer. But as he said in the hospital during his late-night stream of consciousness, I’m the author. And as the author, and his father, I’m damned proud of the fortitude, dignity and humor he displayed during the nightmare that enveloped our lives for 27 months — and which still exists for those now left to mourn him.

In his Scouting, he was a leader and often a guide. So as he fought cancer, his insights and wisdom were often a guide for those around him.

In the hospital, when he thanked me for his “experience” and vaguely referred to the “good characters” he’d encountered, I guess he was recollecting the arc of his life and the people he’d come across in his 20 all-too-brief years. Michael, an avid reader, was paging through his life and viewing himself as one of its characters. A bit squirrelly, incisive, bitingly funny, taciturn and prickly.

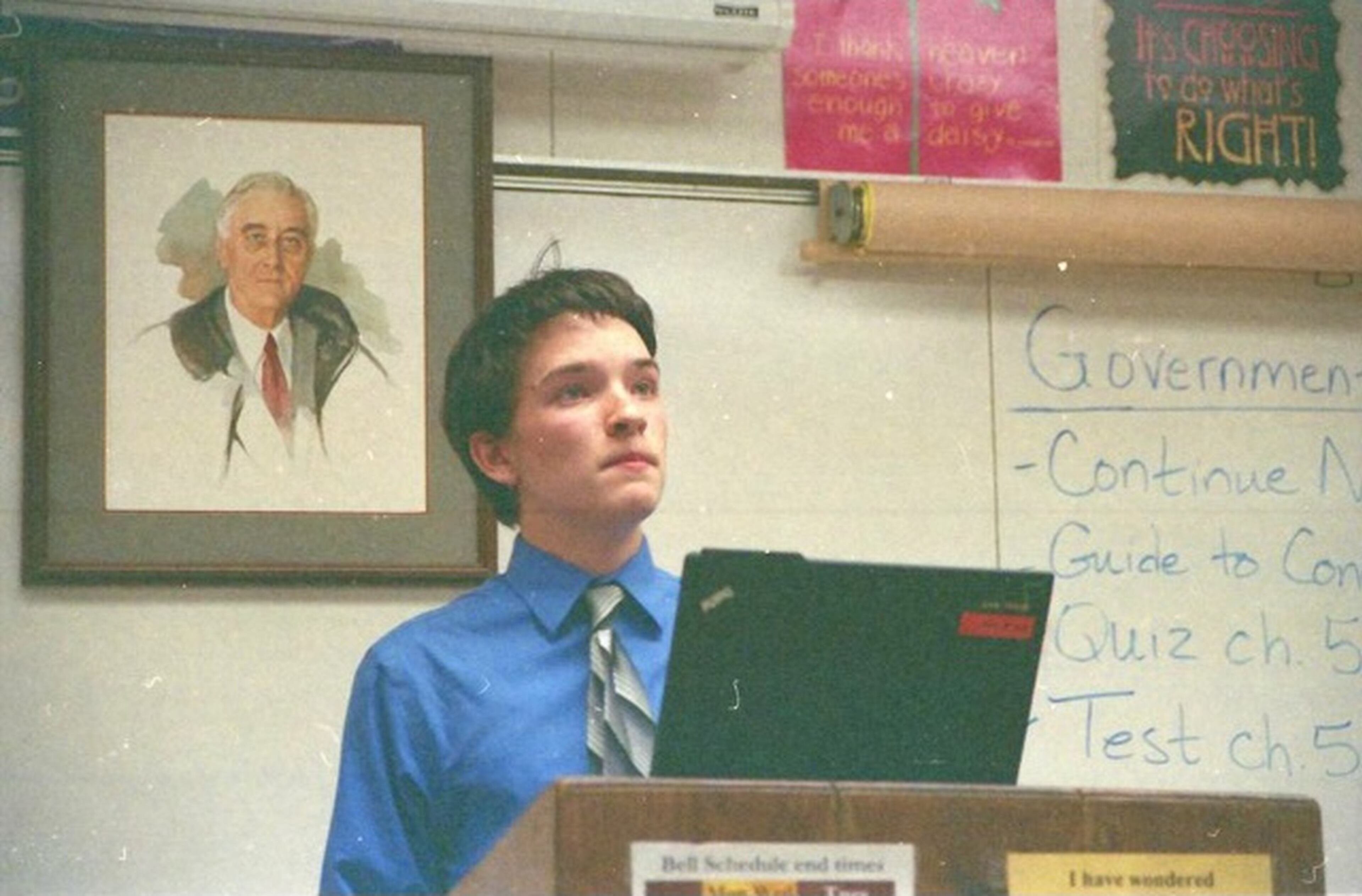

This was a young man with drive. As a kid, he went through several years of speech therapy. As a high schooler, he became the state debate champion. In his written instructions for his memorial service, he quoted me saying that he was the hardest-working Torpy, and the funniest.

He loved being alive and was someone who could make anyone’s day better just by his presence.

His wordplay, coupled with his intensity and will to live, kept us going. He wanted to do whatever it took. He was going to grab the world by its tail.

People often praised him as a warrior for his endurance in the face of such a relentless storm. That kind of talk irked him. He said he was simply someone who was ill, taking the prescribed treatment.

That he did so without ever bitching or crying or uttering “Why me?” just increased the comments about his courage. This irked him even more.

In the past two weeks, we knew it was the end. And once again, a 20-year-old who had thought about — and accepted — this brutal finality was going to be our guide. He had friends come to our home for a last visit. The family discussed good topics for the eulogy, and he determined (properly) that I wouldn’t be able to finish it without blubbering.

He wanted the memorial service at his high school, Marist, at 11 a.m. on Saturday, June 22.

Dress code? Business casual, he responded. We laughed at that.

He was practical to the bitter end. He wrote letters to loved ones to be opened at death. And his list of instructions for us finishes by saying: “Also, if you’re going to print the letters out to get them to the specific people, know that the charger for this computer is a bit broken. You have to get it at a certain angle and hold it there for a while for it to charge, but I’m sure you’ll figure that out.”

We’re sure trying.