OPINION | Unaffordable housing: Hard to get a grip when in ‘The Squeeze’

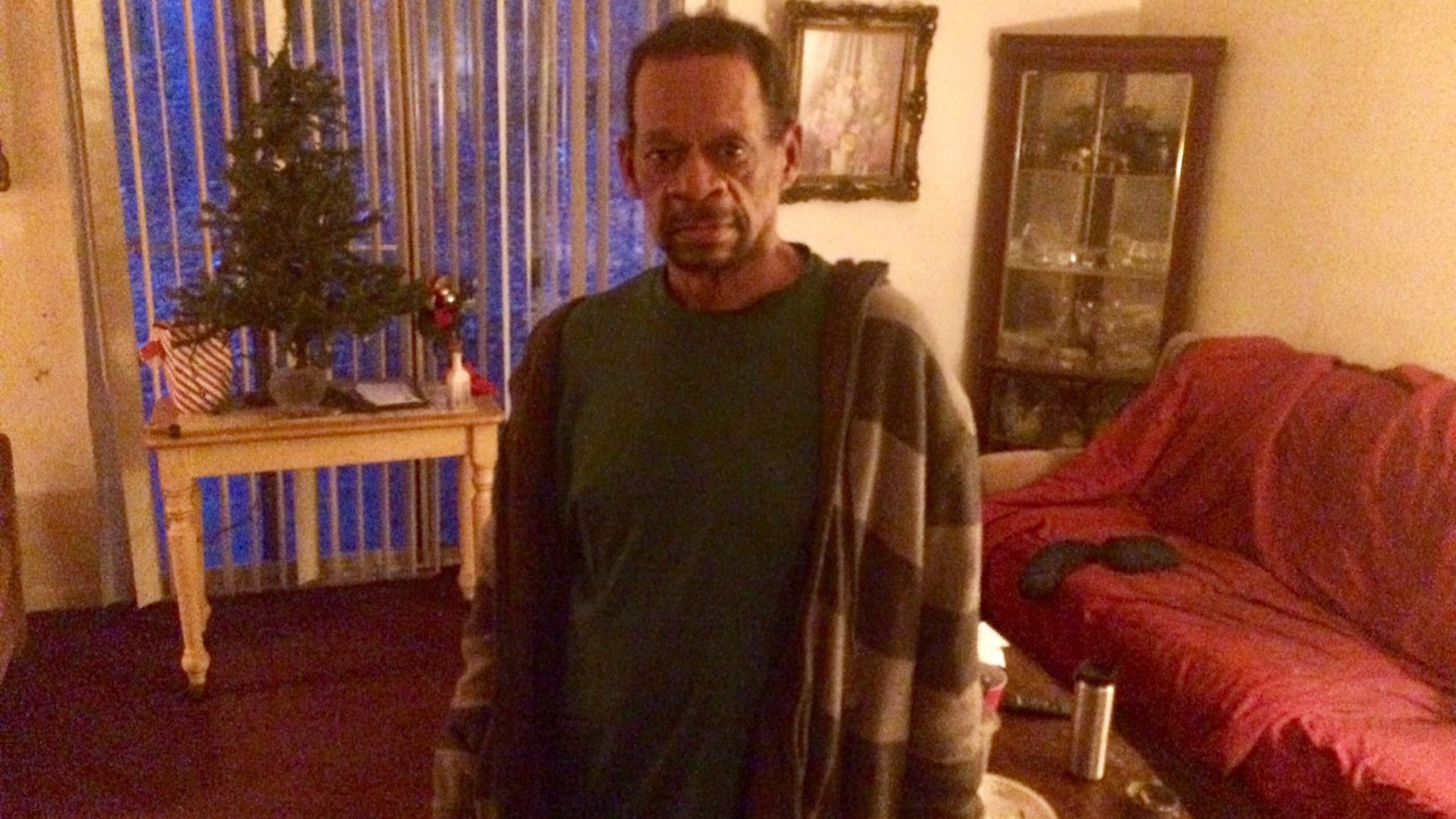

There was a sense of quiet desperation at the home of Joseph Pugh.

The rent for his apartment in Southwest Atlanta near Greenbriar Mall was recently jacked up, and the semi-retired 72-year-old Vietnam-era veteran was feeling the pinch common in many quarters of Atlanta these days.

It’s the affordable housing crisis, but he called it “The Squeeze,” in which the people affected are like toothpaste compressed in a tube.

“The difficulty of finding a place you can afford is traumatic. There’s a lotta pressure on folks like me,” Pugh said. “All these apartments had upped their rent to $800, $900, $1,000. You have people just trying to hang on.”

Through the grapevine, I heard Pugh had called City Hall trying to find a way to catch a break. The new owners of the apartment complex where he has lived for a decade wanted to increase his rent to $990 a month from the $746 he was paying. He negotiated a compromise of “only” $866 a month.

I say "only" because some estimates put the average rent in metro Atlanta at $1,500 a month.

But there’s a problem — arithmetic. Pugh takes in about $1,600 a month in Social Security, meaning he now spends 54% of his income to keep a roof over his head vs. the 47% he had been shelling out.

Either way, it's tough. If you're paying more than 30% of your income to avoid sleeping in the park, then you are a "cost burdened" renter. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 80 percent of people who make under $30,000 a year and 60 percent of those making less than $40,000 are burdened.

"For too many residents, wages have not kept up with rising rents," says the city's Housing Affordability Action Plan. "Between 2000 and 2017, Atlanta's median income increased by 48%, keeping pace with the 46% increase in Atlanta's median home value. But the median rent increased by over 70% during this time."

The city of Atlanta has become a hot real estate market, and as beer gardens and luxury apartments come in, guys like Joseph Pugh are pushed out.

Atlanta officials are trying to get the state Legislature to let them enact rent control.

And Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms has touted a $1 billion plan (half the money would be public, half private) to build or retain 20,000 affordable units by 2026. The city has recently put online an "affordable housing tracker" that says the city has created or preserved 3,500 units in the past two years.

But Dan Immergluck, a Georgia State University professor and housing expert, has been skeptical, saying the majority of the money spent on that effort "is mostly from existing programs."

He did some tinkering on my behalf and found that the city has lost about 8,200 affordable units (those that cost less than $1,000 a month in 2018 dollars) — shrinking from 49,100 such units in 2012 to 40,900 in 2018. He said he’s being very conservative. It has probably lost many more.

So, if the city is creating 1,750 affordable units a year (per its tracker) while also losing 1,365 such units a year, then it's like pouring water into a bucket with holes in it. The mayor last week announced she was pushing for $100 million in bonds to fund the effort.

The gentrification and real estate speculation near the Beltline and around other hot neighborhoods has had a “ripple effect” on rising rents throughout the city, Immergluck said. “It’s moved outward, moved southward and westward.”

Pugh talked about those ripples from his dining room table. “There’s no wiggle room with the rent and the light bill and the gas bill and the phone bill.”

And I suppose you like to eat? I ventured.

Yeah, he said, adding that he often hits some church food kitchens to stock up. We walked into his cramped kitchen, where he displayed some cans of off-brand beans.

I described Pugh as “semi-retired” because he hoped to get a job at the Georgia World Congress Center setting up booths for trade shows. He’d done that work before and said he was in fairly good health other than a bum foot that he’d been getting treated at the VA Hospital.

That means he’d like to stay near a MARTA bus line. He had to get rid of his car a couple of years back when it died and he couldn’t afford the repairs.

“I was getting some retirement from Kmart (where he worked as a distribution center manager for 20 years) but it stopped. I was getting a 401(k), but most of it was in Kmart stock. Then it just went kaboom!”

Kaboom is right.

On his table were piles of notes and phone numbers reflecting his ongoing search to find an affordable senior citizen apartment. He’d been calling around and encountering the same thing — long wait times. Fourteen months, 16 months, 24 months. And more.

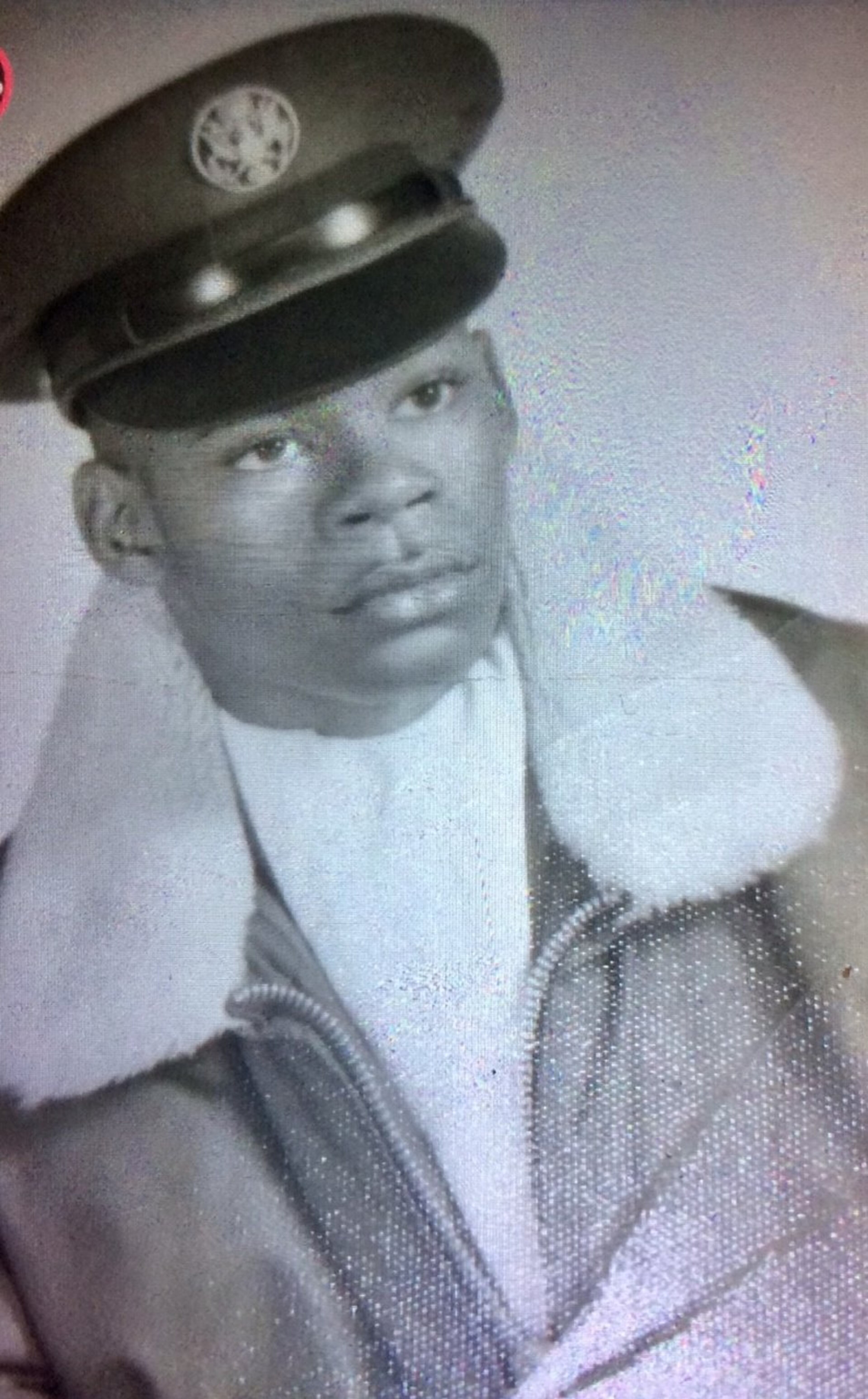

Pugh, the son of a World War II veteran, was in the Air Force in the late ’60s. A photo of his old handsome self in uniform shows the decades can be rough on a fellow.

The government might have some assistance programs for veterans’ housing, he figured, so he made some calls. “They have a program, but you have to be homeless,” he said with a smile.

A city employee who had worked with him said Pugh told her, “Ma’am, I’d rather starve to death than be homeless. If that’s what I have to do, they’ll find me here, starved to death but with my own roof over my head.”

I made a round of phone calls and found he wasn’t kidding about the wait times. The city is apparently filled with senior citizens on hold until others head to that apartment in the sky.

I called a guy connected with the Atlanta Housing Authority and he felt Pugh’s plight. “A veteran?” he asked. “I think we can do something for him.”

It seemed like the agency was moving because a newspaper guy was calling. That doesn’t solve the big picture but, hey, we’ll take it.

I called Pugh, who I hadn’t seen in a couple of weeks. He picked up but was slurring badly.

What’s up? I inquired.

“I’m at the VA Hospital,” he said. “I’ve had a stroke.”

His right side is completely paralyzed and he’s working with therapists to regain some of what he lost.

“I’d like to go home,” he said.

But a whole new battle has ensued.