A Georgia mother’s struggle to unmask a beloved coach as a predator

At first, she thought of Ron Gorman as a godsend.

They met when she was recently separated from her husband and new to Cobb County. Her son, who was starting middle school, had joined the wrestling team on which Gorman was a volunteer coach. Immediately, the sympathetic Gorman seemed to adopt her son into his own brood, including him in family dinners and day trips, paying for things she couldn’t afford, dropping him home after practice.

“I felt really good and comfortable that, wow, this is a great scenario,” recalls Jaquelyn, whose last name is being withheld to protect her son’s identity.

It was Jaquelyn’s mother who first began to suspect that something wasn’t right.

When her grandson called from Gorman’s phone to ask if he could spend the night, she could hear a man’s voice in the background, coaching him on what to say. When he played baseball, Gorman showed up, dragging along his own son who told the grandmother he’d “rather watch grass grow.”

Gorman was taking too much of an interest, the grandmother warned.

By the time Jaquelyn found a shocking message from Gorman sent to her son’s Facebook account, she knew something was very, very wrong.

It was the start of what would be a years-long struggle to expose Gorman as a child predator. Along the way, Jaquelyn came up against what she saw as an indifferent school system, skeptical law enforcement and the insular machismo of the amateur wrestling community. She was called crazy and ostracized. There were times she questioned her own sanity.

In the end, she won a bittersweet victory, but she fears the extent of Gorman’s transgressions may never come to light without a rigorous investigation by Georgia authorities.

Gorman’s case raises questions of institutional accountability at a time of public reckoning over how those in positions of oversight respond to allegations of escalating inappropriate behavior. Specific details of Jaquelyn’s account are supported by interviews with other parents and coaches, as well as police reports, court documents and emails obtained through the Open Records Act.

Gorman began his involvement with Georgia athletics in 2009 as a volunteer coach with Pope Junior Wrestling, a chartered club and the feeder program for Pope High School wrestling, one of the most competitive programs in the state. Parents drove in from surrounding counties to enroll their kids in a program affiliated with Pope’s Jim Haskin, named Wrestling Coach of the Year at least six times over the 20 or so years he’s coached the Greyhounds.

Jaquelyn’s son adored the Gormans, who had recently moved to the area from Pennsylvania. They were a big family in a big house with dogs and game nights and sleepovers. In seventh grade, when he was asked to write an essay about his personal hero, he wrote about Coach Gorman.

“If I didn’t know him then I probably would not be the wrestler I am and would not have a place to go in the afternoons,” he wrote. “He is my hero.”

It was around the same time his mother and his grandmother’s suspicions were starting to take shape. The boy described sports massages from Gorman that Jaquelyn considered inappropriate. Bills for the boy’s cellular service showed numerous text message exchanges with the coach but they were always deleted when she checked his phone. When she told her son he couldn’t go on an overnight camping trip with the Gormans, he flew into a rage.

Then, in August 2011, Jaquelyn checked her son’s Facebook account and saw an expletive laced, sexually charged message Gorman had sent to the 12 year old.

Hands shaking, Jaquelyn remembers immediately printing it out and going down to Pope to confront then-principal Rick Beaulieu.

“He specifically told me, ‘Please do not take this to the police,’” she said. “I said OK because I didn’t know what else to say.”

Beaulieu, now with Cherokee County schools, denies Jaquelyn’s version of events, saying he discussed a coach with a mother but she never complained of an inappropriate relationship. He did not respond to written follow up questions.

Jaquelyn recalls being invited to a meeting with half a dozen school officials, including Beaulieu, head wrestling coach Haskin and the athletic director.

She said they told her Gorman had admitted to sending the message, but allegedly brushed it off as a joke, saying, he “shouldn’t talk to the boys like they’re men.”

The message, reviewed by The Atlanta-Journal Constitution, was crude but ambiguous. It did not solicit sex or refer to any specific act between Gorman and the child.

Jaquelyn said she was informed Gorman would be taking one year off from volunteering with the wrestling program.

Blaine Hess, the head coach of the junior wrestling program, confirmed that Haskin told him Gorman was to be kept away from the kids program.

“I wasn’t really told why,” he said. “I didn’t really probe it. I was just told that there’s an issue, we just don’t want him in the program anymore.”

Haskin and Mathews did not respond to requests for comment. The Cobb County School System said Gorman has never been one of its employees. It did not make anyone available for an interview nor did it respond to written questions submitted by email.

After her meeting with school officials, Jaquelyn said, she took her son to Cobb County police but was told the Facebook message was not illegal. Her son denied there was any sexual contact. She said she continued to plead with Haskin to keep Gorman away from her son.

Now 20 years old, Jaquelyn’s son says he considered the crude message normal locker room talk at the time, especially coming from his buddy Gorman. But his views have shifted as he’s grown. He said he now feels Gorman’s manner of speaking to children was wildly inappropriate and that Haskin should have done more.

“I think Coach Haskin tried to keep [the complaint against Gorman] on the low,” he said. Gorman “kept kinda being able to be put in situations to be able to coach kids.”

After he was asked to leave the junior wrestling program, Gorman continued to coach young wrestlers and receive career encouragement from Haskin. When Gorman landed an unpaid position in 2012 as the director of wrestling at Life University, a private school where Gorman’s wife was on the board, Haskin congratulated him in an email.

“Awesome! I am proud of you my friend,” Haskin wrote. Later, he added: “I always knew it would happen with the right people. YOU.”

At Life, Gorman helped organize youth wrestling tournaments on campus. He founded a women’s wrestling program and a mentoring program that paired college wrestlers with younger boys and girls.

At the same time, Gorman got involved with the Pope High School wrestling program as a parent when his children joined the team, and eventually served as vice president of the booster club. He also volunteered as a national team coach and later a board member for the Georgia Amateur Wrestling Association, known as Team Georgia, a state affiliate of USA Wrestling, the Olympic program.

Even Jaquelyn’s ex, the boy’s father, said at first he didn’t think much of her allegations against Gorman.The father believed Gorman when he apologized for what he said as a “joke,” and his son denied anything inappropriate was happening.

“A lot of these coaches, they get on the same level of these kids,” said the father, who isn’t being identified to protect his son’s privacy. “Haskin and them were looking at it the way I was because this guy had everybody fooled.”

As for Jaquelyn, she kept her distance from anything to do with wrestling. Other parents saw her as not supportive of the team and had heard talk of her grudge against Gorman.

“I felt shunned by the entire community,” Jaquelyn said. “When I showed up, I got looked at, stared at. Nobody would sit by me.”

Gorman, on the other hand, was seen by other parents and coaches as a reliable volunteer, always ready to give rides, bring food and chaperone overnight trips. He was married to a prominent chiropractor and touted his own knowledge of physical therapy. He hosted team parties at his trailer on Allatoona Lake. He was friendly and had a good memory for names.

And if, as some now say, he didn’t seem to know as much about wrestling as he claimed, if the parties at the lake house got out of hand sometimes, if he was especially crass, well, that wasn’t so unusual among young wrestlers and their fathers, in particular.

“It’s just guys bullshitting back and forth,” said the father of a former Cobb wrestler who declined to be identified because he didn’t want his name to be associated with Gorman. “[Jaquelyn] started having this vendetta and nobody believed her. We thought that she was just too wild, kooky, too aggressive.”

Rebecca Mitchell, another wrestling parent, knew nothing about Jaquelyn’s claims against Gorman when a friend of her daughter’s, a 15-year-old Pope wrestler, confided in her and her husband about a disturbing incident in June 2015.

She recalls the teenager saying Gorman had invited him to the lake house, ostensibly to hang out with a handful of the members of the Pope team, even though Gorman’s own children had graduated by then. When the boy arrived, however, he found it was just Gorman, Gorman’s college-aged son and two other college boys. Throughout the evening, Gorman talked about sex and repeatedly offered the younger boy alcohol, telling him “What happens at the cabin stays at the cabin,” Mitchell says the boy told them.

Then, when it was time to sleep, Gorman pressured the boy to share his bed, the boy told the Mitchells. The boy resisted, and slept on the floor. The next morning, he told them, Gorman offered to perform oral sex on him. The boy said he tried to laugh it off as a joke.

Mitchell immediately called the boy’s mother to urge the family to go to the police.

“I told them that I thought that this guy might be a predator,” Mitchell said. “It didn’t sound like this was the first time. … It sounded like a really kind of targeted attempt.”

The mother and father of the boy, whose names are being withheld to protect their son’s identity, confirmed Mitchell’s account, as did Mitchell’s husband, Don Mitchell, a Walton Youth Wrestling coach.

But the boy refused to go to the police. What if he had misheard or misunderstood, he wondered. What if he was alone?

The mother of the boy said they struck a deal that if they found out about another victim, they would go to the police immediately. In the meantime, Rebecca Mitchell contacted Cobb County police, who referred her to the Department of Family and Children Services, where she submitted a report. The Cherokee County Sheriff’s Office confirmed it received a DFCS report on July 8, 2015 in regards Ron Gorman “enticing a child for indecent purposes.”

Haskin assured the parents that Gorman would no longer attend wrestling events. He never mentioned a prior complaint against Gorman, they said.

A few weeks later, in August, Gorman wrote to Haskin asking if he still wanted Gorman to conduct a team bonding excercise with Pope.

“Ron, not going to be able to do anything with (Jaquelyn’s son) still in our program,” Haskin wrote back. He did not mention the incident at the lake house.

Despite Haskin’s assurances, Gorman was spotted at the Kim Andrews Classic at Pope several months later, Rebecca Mitchell said. Haskin asked Gorman to leave only after she and the other mother objected to his presence, she said.

Hess, the coach of the junior wrestling program, said it was only after the incident at the lake house that he discovered the true reason for Gorman’s dismissal from his program years earlier. Hess said he informed Robert Horton, the chair of Team Georgia, where Gorman was a board member.

After initially saying he knew of no allegations against Gorman prior to his arrest, Horton now says Hess’ information wasn’t specific. Gorman explained it away as an underage college wrestler caught drinking alcohol at his lake house, and Horton saw no need to pursue the matter. Gorman remained on the board of Team Georgia until he voluntarily resigned in December 2016.

A little more than a year after it happened, Jaquelyn heard a rumor about Gorman and a boy at the lake house. The news electrified her.

In August 2016, she began posting a message on the facebook pages of Cobb County parent groups, looking for any families that might have had problems with a wrestling coach, without naming Gorman. Rebecca Mitchell saw the message and put Jaquelyn in touch with the mother of the alleged second victim.

The mother of the boy from the lake house was in disbelief that no one had told her what was apparently an open secret about Jaquelyn’s son.

“For nobody to even give us the courtesy of a phone call, or come to our door and say, ‘Hey, we gotta talk about this because we know that there’s another person that this happened to, that it’s been rumored and we called the mom crazy,’” she said. “They were being told and warned and they didn’t do anything.”

Per their agreement, the mother took her son to the Cherokee Sheriff’s Office where he gave a statement to a detective. But the detective was discouraging, the mother said. He told them they waited too long to report — a year — and that if officers questioned Gorman it would be his word against the boy’s.

Meanwhile, Jaquelyn sought to enlist the help of the Cobb District Attorney and the Cobb Police, having been told that a second victim would strengthen her case.

On August 16, 2016, Lt. Eric Yeager replied to an email query from Assistant District Attorney Chuck Boring about Gorman.

“Not sure what they are wanting us to do, we have no new reports,” Yeager wrote, a year after DFCS transferred its file on Gorman to the Cherokee Sheriff’s Office. “Apparently the mom from 2011 is trying to instigate other people against this coach.”

Boring said though there was no case in Cobb, his office continued to investigate.

Jaquelyn took matters into her own hands. She compiled her evidence into three giant three ring binders she labeled the “Justice Folders.” Then, she began posting pleas for information on Facebook groups in Stroudsberg Pennsylvania, where Gorman lived before moving to Cobb.

The response, she said, was overwhelming. Several people even volunteered names of boys they suspected were victimized by Gorman.

The posts also drew the attention of law enforcement in Pennsylvania, which was still reeling from the Jerry Sandusky scandal. Sandusky, a once-celebrated college football assistant coach, was convicted of 45 counts of sexually abusing young boys he came into contact with through a children’s charity he founded.

In September 2016, Pennsylvania State Trooper Brian Noll got in touch with Jaquelyn, and he went to work tracking down the alleged victims.

“It’s not normal that we would seek out victims of crimes like this. But, based on the circumstances and based on the fact that it seemed like something that was possibly ongoing down there (in Georgia), we wanted to, as delicately as we could, reach out to these victims, potential victims, and see if there was anything there,” Noll said.

Six months later, Pennsylvania authorities issued a warrant for Gorman’s arrest. He was taken into custody in Cobb County on March 3, 2017.

On Nov. 3, Gorman pleaded guilty in a Pennsylvania court to sexually abusing two local boys after investigators uncovered a pattern of abuse going back decades. While prosecutors brought charges on behalf of only two victims, they determined there were others for whom the statute of limitations had expired.

Shortly after Gorman’s arrest, Cobb County issued its own warrant for Gorman for assaulting one of the Pennsylvania victims at his home in Cobb in 2010, an incident brought to light by Trooper Noll’s investigation.

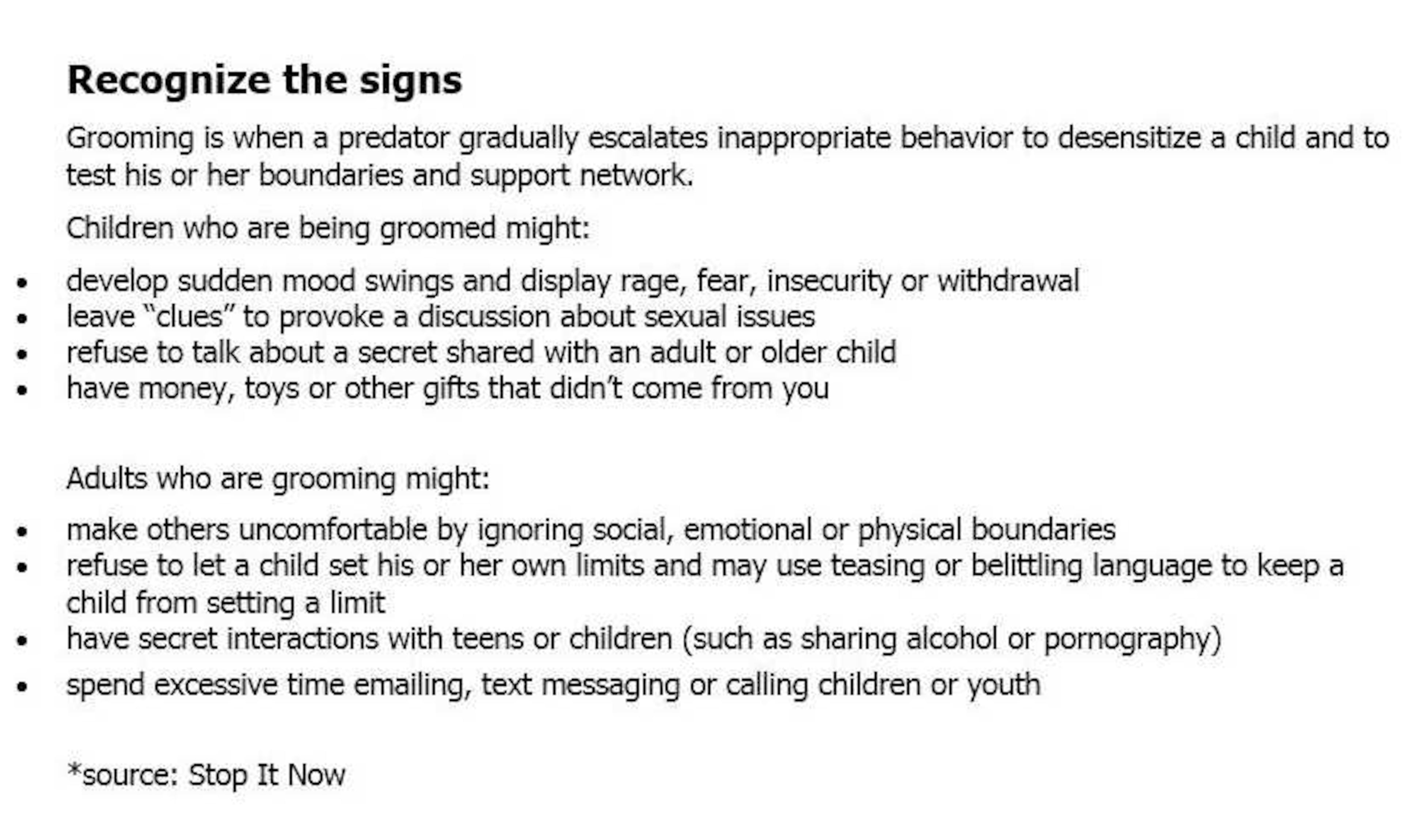

The pattern of grooming laid out in court documents sent a chill through Jaquelyn. Gorman used his position as a wrestling coach to gain the victims’ trust, targeting boys from dysfunctional families. He made them feel loved. He offered chiropractic or sports massages that eventually led to touching and oral sex. He used Facebook for inappropriate communications and instructed his victims to delete his text messages after reading.

“(The victim) stated that he felt pressured into committing and receiving the sexual acts,” according to one affidavit. “He stated that he was very young and he wanted to be a part of the Defendant’s family, so he let it happen.”

If not for the unrelenting efforts of Jaquelyn, Trooper Noll said, Gorman might still be mentoring children and teenagers today. Instead, he’s facing up to 40 years in prison, and she is scheduled to speak at his sentencing on Feb. 20.

“I don’t think that his behavior would have stopped had it not been for her,” he said.

But Jaquelyn is haunted by the possibility of more victims, and the missed opportunities to stop Gorman. State law mandates that people who work or volunteer with children report suspected abuse. Despite Jaquelyn’s urging, the Cobb County Solicitor General’s office declined to prosecute Haskin for failure to report.

Melissa Carter, the director of the Barton Child Law and Policy Center at Emory, said there appeared to be multiple occasions when adults in positions of responsibility for Jaquelyn’s son and other children failed them.

“The law itself is just a minimum, and often the law doesn’t answer for us what the ethical or moral thing to do is,” Carter said. “We all, as adults, should be aware of the signs and symptoms of abuse.”

* An earlier version of this story identified Pope’s athletic director in 2011 as Josh Mathews. It was Steven Craft, who confirmed to the AJC that he met with Jaquelyn at that time to discuss Gorman. Jaquelyn says she met with Mathews, who became athletic director in 2012, at a later meeting.

More Stories

The Latest