The city of Atlanta impounded nearly 3,000 improperly parked e-scooters off city sidewalks over the summer, and released all the devices back to the respective companies that own them without collecting a penny.

The impound fees would have amounted to at least $200,000, and the city has no explanation as to why they were not collected.

Scooter enforcement has been an ongoing issue for city leaders since four riders were killed over the summer. One of the biggest complaints from residents is improperly parked scooters blocking sidewalks.

VIDEO: Previous coverage of this issue

Public Works Commissioner James A. Jackson Jr. told a council committee last week that his department impounded 2,897 scooters between July 1 and Sept. 30. Council members were flabbergasted at the city’s failure to collect the fees.

"If me or you get our cars impounded, and show up to the lot and try to get them back without paying them, we'd be laughed off the lot," Councilman Dustin Hillis said.

In an interview after the meeting, Hillis said the city likely has no hope of recouping the lost money: “That may just be our fault.”

On average, the city impounds 50 scooters daily, and should collect a $75 impound fee for each, Jackson said. There is also a $25 charge for each additional day the devices remain impounded.

The permits allowing scooters to be on city streets require companies to comply with Atlanta’s scooter regulations — including paying impound fees, Jackson said. As part of the impound process, the city photographs where the devices are found and notifies the companies, according to Jackson.

RELATED COVERAGE:

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Jackson didn’t provide an explanation to the council committee about the city’s failure to collect impoundment fees, and Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms’ office did not respond to the question: How much, if any, in impound fees has the city collected over the past 20 months?

“We’re working to enhance the enforcement and oversight so that we minimize our staffing requirements as well as ensure that we are receiving the funding from impoundment activity,” Jackson told the utilities committee.

Jackson said the department is revising the way it collects impound fees and is waiting for approval from the Mayor’s Office. He did not say what changes are under consideration but said the department is talking with the city’s law department to see how far back they can collect the fees.

A spokesman for Lime scooters said the company hasn’t paid impound fees because they are still waiting to receive invoices from the city. Nima Daivari said the company received one invoice in May, for February and March impounds, but it wasn’t paid because there was no documentation detailing the number of scooters impounded and the corresponding violations.

“We still don’t have a lot of clarity,” Daivari said.

In the meantime, Daivari said the company has a team of 40 employees dedicated to addressing parking issues in Atlanta. The company also has access to the city’s 311 system and is responsive to complaints submitted there, he said.

“We are not perfect and definitely want to resolve this in an amicable way with the city,” Daivari said. “But we definitely want to get a better process in place.”

Educate, then enforce

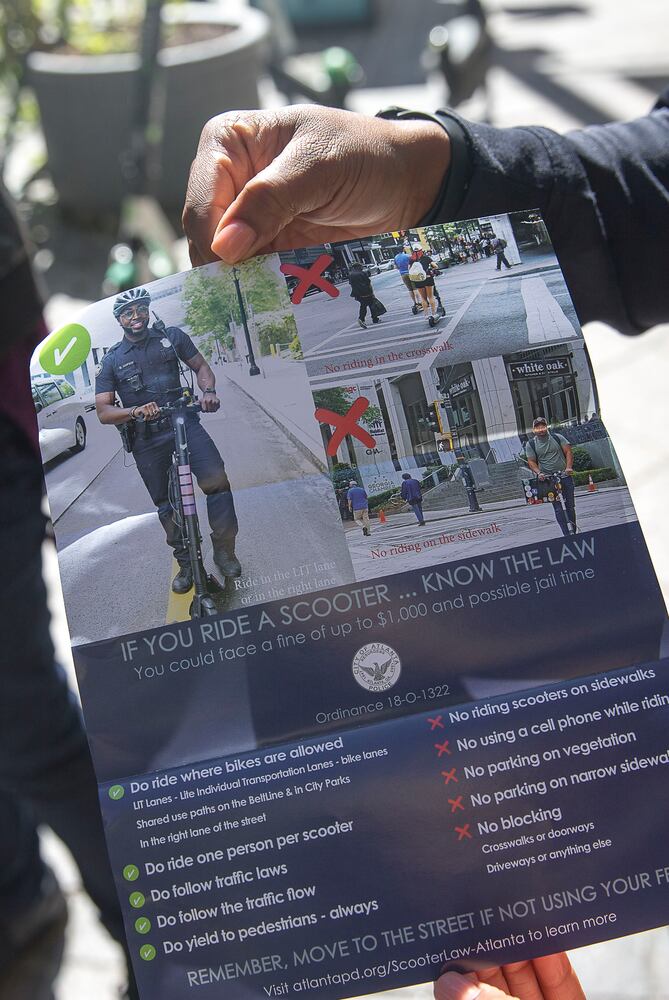

Atlanta police officer Ayesha Abdul-Hakeem reports to her job every day well-armed to deal with scooter riders. Her weapon of choice: a pamphlet.

Abdul-Hakeem is a foot-patrol officer whose day-to-day duties range from tracking missing persons to investigating robberies.

And now those duties include enforcing scooter regulations.

Haphazardly parked scooters are one of the biggest complaints against the devices, but Abdul-Hakeem also sees riders zipping on crowded sidewalks or in and out of traffic. Officer C. Walden said he’s seen parked scooters fall into the street and create a hazard for drivers.

There were few scooter riders on a recent brisk October day, but Abdul-Hakeem still kept her pamphlets at the ready. She handed one to a rider as he cruised down a Peachtree Street sidewalk near 5th Street.

The rider slowed, took the pamphlet and thanked her. He then sped on his way.

Abdul-Hakeem said she tries to avoid running after scooters.

“The main concern is if you run up on them, they may wonder: ‘Why are the police running after me and did I do something wrong?’” she said.

Police Zone 5 Commander Darin Schierbaum said his officers are reluctant to hand out citations to first-time offenders, many of whom are tourists. Zone 5 encompasses downtown Atlanta and Midtown, areas that have some of the highest concentrations of scooters.

“But if it’s our second or third day of directing you to get into the street, that person will likely get a citation,” Schierbaum said.

Atlanta police have issued 54 citations since scooters first appeared on Atlanta streets.

Hillis said he would like to see more citations and fewer pamphlets handed out.

“I think each officer should use their discretion, but there shouldn’t be a blanket policy that we hand out warnings to tourists regardless of the violation,” he said.

Councilman Amir Farokhi credited the department’s education efforts as the reason he’s seen fewer violations. But he, too, would like more enforcement.

Farokhi’s district includes the scooter hotbeds of downtown and parts of Midtown, and he’d like to see companies held more accountable.

“We need to place a bigger burden on (companies) to … shape the riders’ behavior,” he said.

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

‘The fewer companies we have, the better’

The city has some big decisions to make related to scooters.

There are currently seven companies with permits to operate in the city. As those permits begin expiring in February, councilmembers would like to see fewer companies with scooters on city streets.

Office of Mobility Interim Director Cary Bearn said she thinks the city should decrease the number of scooter companies doing business in the city to better regulate them. There are currently about 6,000 of the devices within the city limits.

“The fewer companies we have, the better able we are to manage the program and the fewer advantages they have to perform poorly,” Bearn said at a transportation committee meeting last week.

Bearn said the Department of City Planning, which houses the mobility office, is in the process of rewriting the scooter legislation so that it can limit the number of permits.

“It’s a goal and there are definitely ways to achieve that goal, but we haven’t identified the paths that we’re going down,” she told the AJC.

Scooter companies pay a $100 application fee and $12,000 to have 500 devices in the city. They pay $500 for each additional scooter. A city spokesman said $542,000 has been collected in permit fees.

Hillis said he favored the city permitting one or two companies that could be held to a high standard.

“It would be much easier to police one or two vendors than it would be the current free-for-all,” he said.

Farokhi said he thinks the city should limit it to three to five companies, to make sure there are enough of the devices to meet demand and make sure “there is equitable access to them.”

The Department of City Planning, which is charged with issuing permits, will send out a public survey this month. The city also plans to hold a work session and draft updated legislation in December.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured