The charges

- Making a false statement: Doug Cotter allegedly overcharged DeKalb County for work performed at Lee May's home when he was a county commissioner.

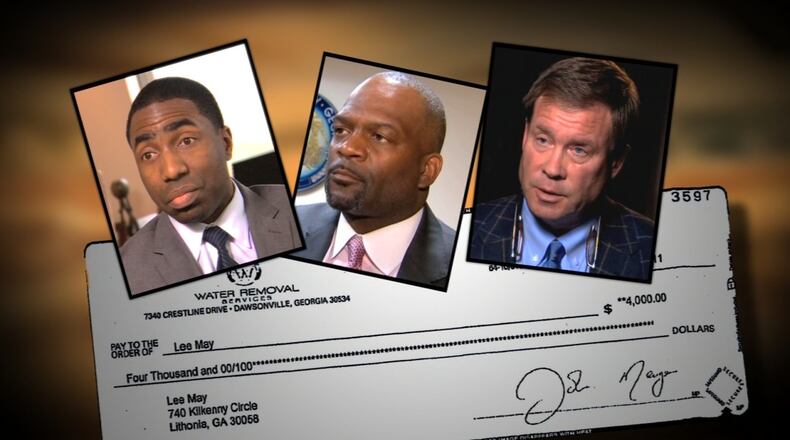

- Theft by taking (two counts): Cotter and Morris Williams allegedly stole $4,000 from DeKalb County.

- Conspiracy to defraud a political subdivision: Williams allegedly accepted a $4,000 check from Cotter that had been made out to May.

- Conspiracy to defraud a political subdivision: Cotter allegedly conspired to use May's name to deliver $4,000 to Williams.

Source: Indictment of Cotter and Williams

A grand jury on Tuesday indicted two men who allegedly used Interim DeKalb CEO Lee May's name to steal $4,000 in public money.

Former Chief of Staff Morris Williams and contractor Doug Cotter face felony charges of theft and conspiracy stemming from repairs at May's home in 2011. Cotter also is charged with making a false statement. It's the latest in a string of a corruption accusations that has plagued the county.

May has not been charged with a crime. He said he hopes the criminal cases resolve questions about why a check was written with his name on it, who cashed it, and who received the money.

“I’ve never participated in any illegal activity,” May said during a press conference Tuesday. “I feel like I’m a victim. … This moves us a step closer to resolving this once and for all, and I’m happy for it.”

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Channel 2 Action News first reported suspicions surrounding the transaction in April 2015.

Cotter was working for Alpharetta-based Water Removal Services and charged the county $6,500 to fix May’s floors, which were damaged by a raw sewage backflow in his home near Lithonia. Cotter has said Williams told him to bill the county for that amount, even though he had agreed to do the work at cost, or $2,500.

Soon afterward, Cotter told Channel 2, Williams asked him to cut a $4,000 check to May, who was a county commissioner at the time.

May said he never saw the check or the money. The check bears an apparently forged endorsement, and Cotter has said he cashed it at a Dawsonville liquor store owned by his family. Cotter said he later met Williams for coffee at a McDonald’s in Decatur and gave him the money.

Williams disputed Cotter’s account during a brief phone conversation with the AJC last year, but he didn’t clarify whether he received any money.

“County employees and those who do business with the county are held to a higher standard because they provide or use resources to further the best interests of DeKalb citizens and businesses,” said DeKalb District Attorney Robert James in a statement. “If you betray the public trust, you must be held accountable.”

After May became the county’s interim CEO in July 2013, Williams left his job as chief of staff in June 2014 to become a deputy chief operating officer overseeing public works and infrastructure. Williams abruptly resigned in March of last year as authorities were investigating the county government.

An attorney for Williams didn’t return a phone message seeking comment.

Cotter plans to plead not guilty and “vigorously defend” himself, said his attorney, Steve Frey.

An outside investigation of corruption in DeKalb accused Williams of lending money to May, an alleged violation of the county’s ethical rules. The corruption report by Mike Bowers and Richard Hyde said investigators couldn’t determine if the loan was connected to the $4,000 check.

May stopped the Bowers/Hyde investigation after six months as its cost reached $850,000 with no end in sight. The investigators' Sept. 30 report called for May to resign and cited "appalling corruption and a stunning absence of leadership" in county government.

“This is further proof that we found significant corruption at the highest levels of DeKalb County government,” Hyde said Tuesday. “It’s too bad our investigation was obstructed and shut down before we could conclude our independent investigation.”

Joel Edwards, a DeKalb resident who has been speaking for years about the need for more honest government, said the charges against Williams and Cotter are a step in the right direction.

“We have to clear the sky of this cloud of corruption in DeKalb County,” Edwards said. “In my opinion, it’s a good thing that it’s happening.”

DeKalb's government has been mired in criminal trials and suspicions of wrongdoing for years, resulting in the convictions of several prominent officials.

Along with CEO Burrell Ellis, Commissioner Elaine Boyer and schools Superintendent Crawford Lewis, more than 40 DeKalb government officials and contractors have been found guilty of crimes since 2011.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured