Atlanta erecting markers about slavery next to Confederate monuments

Atlanta is about to publicly reckon with slavery and its monuments to the Civil War.

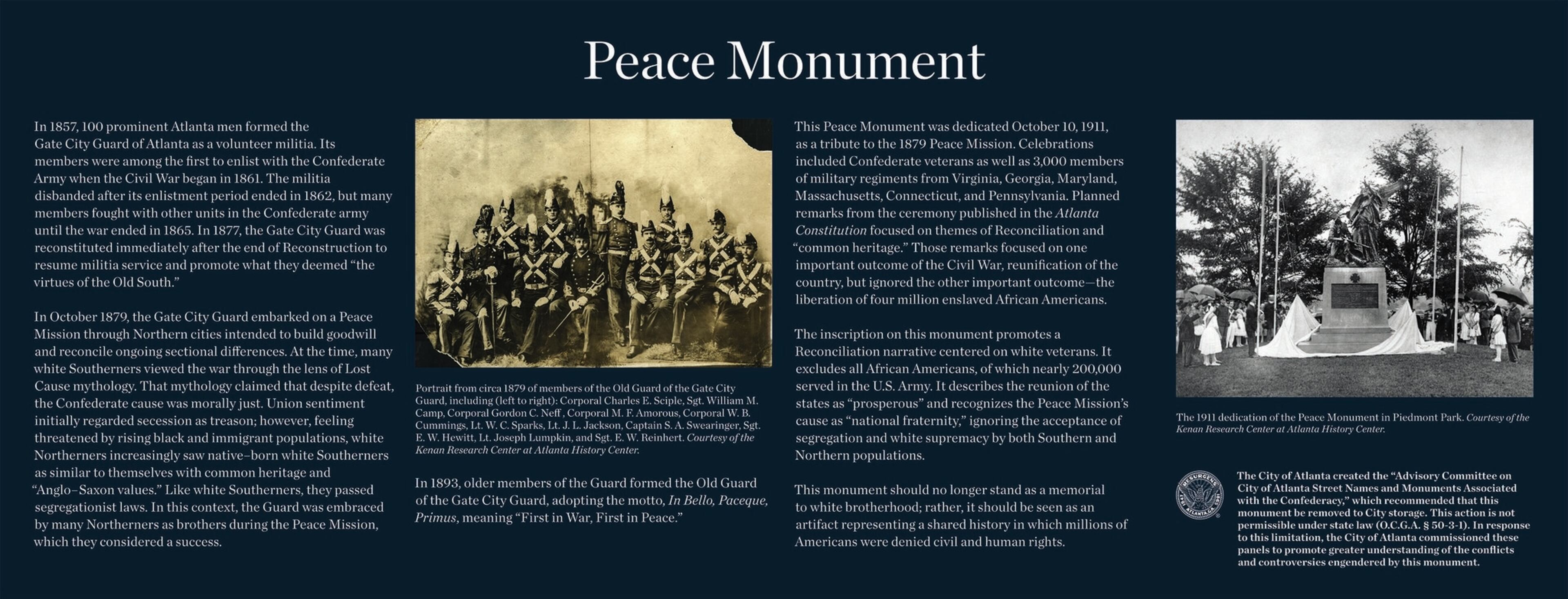

As early as next week, the city will begin installing a series of contextual markers around four of its most prominent Confederate monuments: the “Peace Monument” in Piedmont Park, the “Lion of Atlanta” and the “Confederate Obelisk” in Oakland Cemetery, and the “Peachtree Battle” marker in Buckhead commemorating the Battle of Peachtree Creek.

The markers have been many months coming, after former Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed created a blue-ribbon commission in late 2017 to address the city’s Confederate monuments and street names.

The existing monuments are prohibited by state law from being removed or obscured. Each of the contextual markers will be placed either near the foot of or beside the monuments.

» PHOTOS: Confederate memorials in metro Atlanta

» PREVIOUSLY: Plan to address Atlanta's Confederate monuments hits snag

The markers are significant because they explicitly discuss slavery as the cause of the war. They also acknowledge the campaigns of racial terror waged on African Americans after the war and the legacies of segregation and disenfranchisement that persisted for generations. And, in the case of the Peace Monument at Piedmont Park, one of the two panels to be installed there will highlight African American achievement and resistance from Reconstruction through the early 20th century.

Atlanta is the first city in the nation with Confederate monuments to add contextual markers in states with no-removal laws, according to Sheffield Hale, president and CEO of the Atlanta History Center and a key member of the city committee responsible for addressing Confederate monuments.

“This city has chosen not to stay silent about the monuments in our midst,” said Hale. “We’re going to tell the truth.”

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reviewed three of the panels on Wednesday at City Hall. Panels for the towering Peace Monument in Piedmont Park are about 6 feet by 2 feet, whereas the Peachtree Battle panel is roughly two feet square. The panels for Oakland Cemetery are being printed this week.

The city council approved the panels by resolution in late May. The history center paid $11,000 for the panels to be produced. Throughout the spring and early summer, representatives from the Historic Oakland Foundation, the history center, the city’s office of historic preservation and City Council Member Carla Smith, who has led the monument committee, worked on language for each sign.

Cities across the South have convulsed over how to deal with their Confederate iconography. From New Orleans, where then Mayor Mitch Landrieu made an impassioned case for removal as a moral imperative, to Charlottesville, where Heather Heyer was murdered by a white supremacist, the legacy of the Confederacy has been a cause of conflict and violence. In the aftermath of Heyer’s murder, protesters defaced the Piedmont Park monument with red spray paint. That led the state legislature to pass a law this year strengthening the penalties against vandalizing the monuments and making it harder to remove them.

Reed’s blue-ribbon commission led to the creation by Mayor Keisha Lance Bottom’s administration of a three-member panel led by Smith, along with fellow Council Members Natalyn Archibong and Michael Julian Bond. One of the recommendations was completed earlier this year: renaming the former Confederate Avenue to United Avenue. Another was the contextual panels.

“It is now real,” said Smith on Wednesday of the new markers. “It means we actually didn’t drop the ball.”

» RELATED: Georgia House approves bill protecting Confederate, state monuments

» MORE: DeKalb's Confederate monument to receive contextualizing marker

At least one member of the original blue-ribbon commission, however, said that while he was happy to see the city follow through on the panels and renaming Confederate Avenue, he felt more work should be done.

“This approach to mediate or add context is an excellent starting point,” said Douglas Blackmon, a Pulitzer-Prize winning author. “But we can’t ignore that there are a couple dozen other streets that glorify slave owners and slave traders.”

» RELATED: The complex task of writing history

Though the panel is finished with this phase of its work, Archibong said, people will still debate the legacy of the war. And that is the point, she said.

“We’ve balanced this history with context the will allow the public to understand our collective journey,” Archibong said. “We’re not rewriting history, we’re giving it context.”