APS tries to aid cheating victims but impact is small

It’s been nearly a decade since Kyrsten Burch took one of the high-stakes standardized tests that would make convicts out of cheating teachers and catapult Atlanta Public Schools into infamy.

She was among thousands of Atlanta students whose 2009 exams, on which many wrong answers had been erased and corrected, exposed a massive cheating conspiracy by educators who snagged bonuses based on bogus scores and robbed students of extra help, such as tutoring, that they might have received if the phony results had not masked their academic struggles.

In all, 32 teachers and administrators were later convicted or pleaded guilty to crimes. It took APS several years to begin to atone for the past transgressions by providing tutoring, coaching, and other services to Kyrsten and other students identified as likely cheating victims.

But after an analysis of the first three semesters and $7.5 million poured into that effort, there's scant hard evidence to show that Target 2021, named for the graduation year of the last class of potentially cheated students, is making much of a difference.

The recent evaluation by a Georgia State University researcher found a small positive impact on grades and a hazy or mixed effect on attendance, graduation and other outcomes.

“For the most part, either no results or very inconclusive,” is how Tim Sass sums up his findings. The relatively small number of students included in the study made it hard to arrive at conclusive results. There were roughly 3,000 students eligible for the program when it started in January of 2016 and 1,483 enrolled as of last month.

Kyrsten is grateful for the help, even though, by her own assessment, the toll the cheating trouble took on her was emotional, not academic.

Related: Movie to tell story of APS cheating scandal

“It was just a lot going on at that time. That’s what affected me, when it blew up,” she said. “I wasn’t really sure what a scandal was, so I was like, ‘What’s going on?’”

Now a poised 18-year-old with green streaks in her hair, she juggles the classes and extracurricular activities of a high-achieving high schooler: Tuba, shot put, drill team, mock trial, to name a few.

She credits the program for helping her conquer college admission exams. She wasn't familiar with the SAT and ACT tests, which are key to being accepted into college, until her support coach gave her a study guide. The Maynard Holbrook Jackson High School senior couldn't have afforded the book on her own, and that's one of the ways she's benefited from Target 2021.

“I think that it was a great thing that the district actually acknowledged that we had been through something, and they actually wanted to help. That was a big thing for me,” said Kyrsten, who plans to attend Wesleyan College.

District and program officials point to those types of successes as proof of the program’s value, even though the recent evaluation found mostly slight or no impact on student outcomes.

The report identified a small improvement in grade point averages for core high school classes. Target 2021 students increased their GPAs from 75.7 in the fall of 2015 to 76 in the spring of 2017, based on a 100-point scale. A comparison group slipped from 76.7 to 76.1 during that same period.

But the rest of the analysis yielded few clear-cut results, Sass said.

Program participants missed an estimated 1.3 to 1.7 more days of school than the comparison group, according to APS documents. They also appeared to have a slightly higher graduation rate, though there are too few students to provide a precise estimate.

Some program goals couldn’t be accurately measured because relevant numbers weren’t available. Improving reading is a focus, but most of the students don’t take reading-specific tests.

Some cheating victims were promoted from grade to grade even though they weren't prepared. Much of the cheating took place in schools in the city's poorest neighborhoods, and research shows that cheated students fell behind in reading and English language arts.

Target 2021 attempts to make up for that, but not everyone is convinced it’s working.

“The data didn’t really support any changes. We aren’t getting the bang for the buck,” said Shawnna Hayes-Tavares, who serves on the program’s advisory board and has a child enrolled. “This was a promise to our community that we have failed on.”

Atlanta school board chairman Jason Esteves and superintendent Meria Carstarphen have acknowledged they would like to see better outcomes.

“It is a very, very heavy lift. The kids are working very hard … even to get kids back into the cohort we had to go out and recruit children who dropped out to come back to APS where possible,” Carstarphen told the board in December. “It still feels like the beginning of the work, and we do intend to see this all the way through.”

Carstarphen did not comment for this story, but the district released a statement affirming its commitment to the program.

Target 2021 is scheduled to end in three years, when the last class of cheating victims graduate. A budget for the remaining years has not been finalized.

Esteves said the program evaluation shows the district still has “to help these students get the services they need and the educational opportunities they deserve.”

“I was not disheartened by it,” he said. “If anything, I was re-energized to … commit until the very end of the program.”

Keeping students focused on school

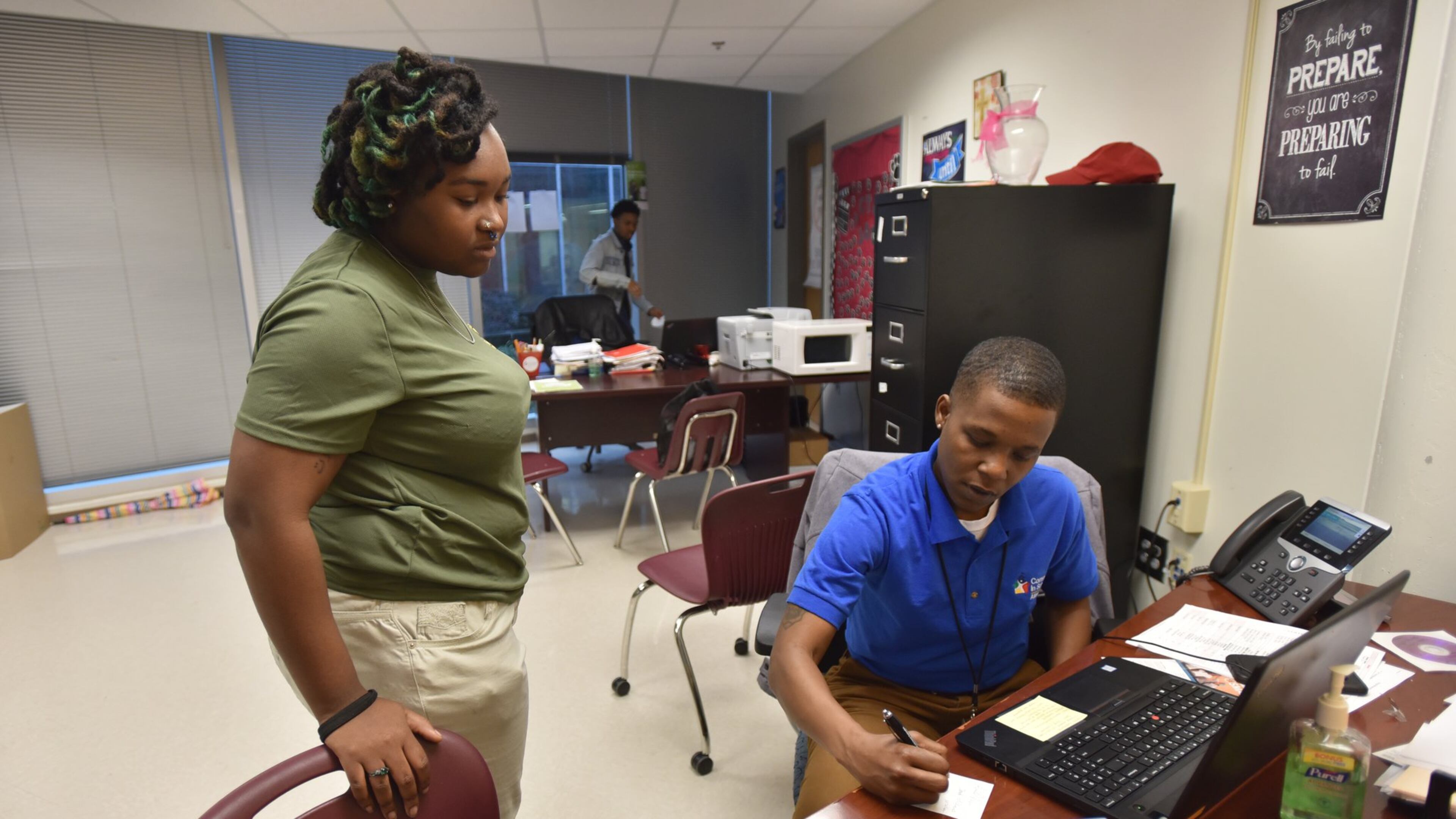

On a typical school day, Valencia Dennis arrives at Jackson High School by about 7:30 a.m. Lately, she’s greeted her students at the cafeteria door with a dose of morning motivation and a bottle of hand sanitizer to ward off winter germs.

As a student support coach with Communities in Schools of Atlanta, the organization APS hired to provide mentoring, academic and family support, and parent outreach, she monitors the progress of about 70 Target 2021 students.

Her office, which also serves other CIS programs, is stocked with study materials, school supplies, and a food pantry with boxes of macaroni and cans of beans.

Students drop in to ask for help or chat. Kyrsten stops by once or twice a week to check in or seek college advice.

Dennis keeps tabs on attendance, behavior, and academics. If students struggle in class, she can refer them to a tutor. If they can’t get to school, she can help with bus fare.

“Anything that takes our focus off of school, they are going to try to fix that problem, and they will fix that problem,” Kyrsten said.

Paul Askew, a 17-year-old senior, said he sometimes skips lunch to do homework in the office. He joined Target 2021 last year.

He remembers taking tests while at Peyton Forest Elementary School, one of 44 Atlanta schools where state investigators reported cheating.

“It affected me because it made me think, like, ‘Did I need help? Or do I need to push myself more?’ ” Paul said. “So, like ever since they were talking about the cheating scandal it made me work harder in the classroom.”

While he thinks he would have done OK without it, he credits the program for bumping his grades from Cs and Bs as a freshman to all As in his first semester as a senior.

The program supports many students whose parents aren’t at home when they’re doing school assignments, he said. “They can tell me to do my work, but they can’t physically help me because they have work.”

Support coaches sometimes visit students’ homes. They’ll try to figure out why they’re missing class or provide homework when students are suspended so they don’t fall further behind. They may discover a family can’t pay for housing or utilities and then offer help.

Those are the intangible benefits that Denise Wright, senior program manager for Communities in Schools, said aren’t seen in a statistical analysis.

Lifelines tossed too late?

Motivated, ambitious students such as Paul, who wants to be a nurse, and Kyrsten, who is interested in environmental studies, praise Target 2021 for tailoring services to their needs.

But critics contend the program hasn’t reached enough victims.

Hayes-Tavares, who testified during the cheating trial about her children’s surprisingly high test scores, thinks APS should have moved more quickly to start the program.

Several thousand likely victims had already left for other schools, graduated, or dropped out by the time the district got going. And while prosecutors believe cheating took place in Atlanta for years before the 2009 Criterion-Referenced Competency Test, the Target 2021 program is only for students who were in classrooms where cheating was suspected and who had five or more wrong-to-right erasures on the math, reading or English language arts exams from that year.

Most current participants are now in high school, a late age to begin helping students who lagged for years in reading and writing. Sass’ report notes that once students are in high school, “it is hard for even the best designed and implemented interventions to have substantial effects.”

It takes time to master a subject or skill, she said.

“We don’t know where the breakdown started with the cheating. We don’t know how far behind they were,” she said. “We are still not where we need to be.”

Related: Cheating scandal stained APS

After the cheating, APS added more tutoring but did not initially single out student victims for extra help. In the tumultuous years after the scandal broke out, previous district officials were busy putting out fires, said Esteves, who joined the school board months before the board hired Carstarphen in 2014.

Under Carstarphen, the district decided to try to identify the students whose answers were likely changed. Budgeting money, developing the program and then hiring partners to implement the plan took more time, said Esteves.

“The fact that we started late is not in our favor, but to those who are criticizing our efforts we are open to that feedback,” he said.

Olivine Roberts, assistant superintendent of teaching and learning, said the district has tweaked the Target 2021 program based on the results so far.

It now offers more in-school tutoring because many students weren’t coming to after-school sessions. Officials sharpened the attendance strategy to focus on children who miss the most school. That’s where the classroom checks, phone calls, and home visits from Dennis and other support coaches come in.

The district also is pulling data more frequently to make sure students are on track to graduate so that it can quickly help failing students.

APS sought to engage more parents of likely cheating victims by expanding efforts beyond workshops and meetings. It spent $2,999 to launch an online Target 2021 informational app that had been downloaded 133 times as of early this month.

Another, separate effort aimed at helping victims who aren't in school anymore has not attracted the necessary millions of dollars and volunteers. Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard, Jr., whose office won racketeering convictions against 11 teachers and administrators in 2015, said he didn't realize the enormity of the task when he first championed the idea of opening an academy. He said he hasn't given up.

He praised APS for trying to help still-enrolled students.

But other victims have since left school, been incarcerated or are unemployed. Some who were cheated out of an education are merely existing, Howard said.

“For many of these kids, this was their only opportunity. This is it for most of them, and at no fault of their own, this opportunity had been taken away from them. And, I guess the question three years later is: ‘As a community, what are we going to do about giving it back?’ ”

A total of 1,483 Atlanta Public Schools students were enrolled in the Target 2021 program as of January. Here are the 10 schools with the most participants:

Mays High School: 278

Douglass High School: 169

Jackson High School: 145

South Atlanta High School: 124

KIPP Atlanta Collegiate High School: 116

Therrell High School: 116

Carver High School: 113

Washington High School: 105

Carver Early College: 60

B.E.S.T. Academy: 59

— Source: APS

How we got here

In 2011, state investigators confirmed widespread cheating on 2009 standardized tests in Atlanta Public Schools. The trial for educators facing charges linked to the scandal ended in April 2015. It took time under Superintendent Meria Carstarphen, hired the year before, to identify the thousands of students who may have been harmed by the cheating and provide help such as tutoring or social services. The remediation program launched in early 2016. An evaluation of its first three semesters showed largely inconclusive results.