For at least a decade, residents of Juliette have believed the well water in their community is contaminated. Plant Scherer, one of the largest coal-fired plants in the nation, is the cause, according to allegations in a lawsuit filed last week in Fulton County Superior Court.

It is the second time that residents of the town an hour south of Atlanta have taken legal action against Georgia Power, which owns and operates Plant Scherer, and this time they hope to see the company held accountable.

“We know a lot more about the situation now than we knew then,” said Stacey Evans, former gubernatorial primary candidate and the attorney representing 45 former and current residents of Juliette and Forsyth. “We have access to documents that support all the allegations that we put forth in the complaint. That includes several things that weren’t discussed in 2013.”

Back then, more than 100 residents filed a lawsuit alleging that Plant Scherer was harming their health and property. The lawsuit was dismissed with no decision. Georgia Power officials said the current lawsuit, like the previous one, is without merit.

“Our employees and retirees also live and raise their families in the communities we serve, and if our operations were causing harm to residents, we would take every action necessary to resolve the situation,” said Dr. Mark Berry, vice president of Environmental & Natural Resources for Georgia Power, in a statement.

Plant Scherer began operating in 1982 and is one of the largest coal plants in America though it only ran at 40% capacity in 2019, according to recent industry reports. The plant generates tons of coal ash — waste from coal-burning plants that contains arsenic, chromium, lead and other substances harmful to human health.

An estimated 15.7 million tons of coal ash sits on the site in a 776-acre unlined pond. Unlined ponds can allow the toxic substances to leak into groundwater that flows directly to residents’ water wells. Residents have complained about a range of health issues, including various forms of cancer. A study in 2011 found Monroe County had cancer rates higher than the state and national averages.

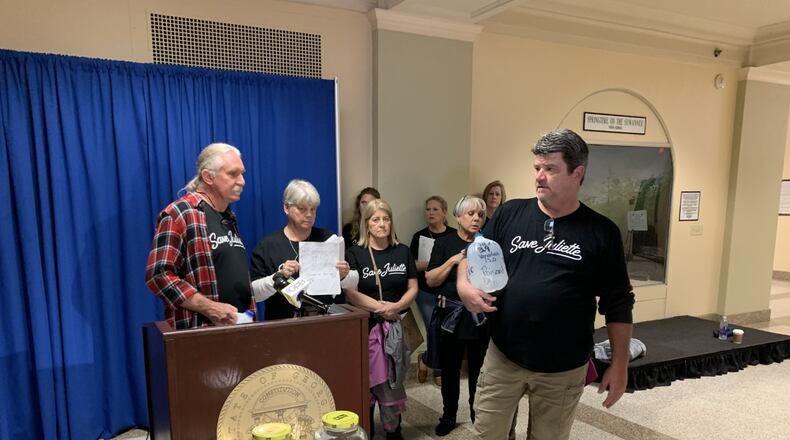

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

New evidence that was not previously available indicates the company should have known its construction of Lake Juliette would disrupt the surrounding environment and increase levels of pollutants. The suit also claims that Georgia Power has continued to discharge pollutants into the air, groundwater and surface water.

Residents are seeking damages for personal injury and property damage. They are also asking for the establishment of a medical monitoring fund and want Georgia Power to be prevented from engaging in activities that result in trespass or nuisance, according to court documents.

In June, Monroe County officials provided one form of relief when they approved $20.3 million in revenue bonds, of which $16.3 million will go toward installing almost 73 miles of water lines in a triangle around Lake Juliette. Macon Water Authority will supply water to more than 850 residents, many of whom had resorted to using bottled water for drinking and cooking. The first phase of the three-phase project should be completed by the end of the year, said Richard Dumas, spokesman for the county.

“Finally, it is a sigh of relief,” said Andrea Goolsby, whose family in Juliette can expect to have drinkable water in about a year. “I think they are starting to see a glimmer of hope, some light at the end of the tunnel.”

Goolsby said she hopes the actions in Juliette help bring attention to the dangers of coal ash. Corporations and local governments need to address the ongoing issues with coal ash management and disposal, she said. Though several coal ash bills made gains in the most recent state legislative session, bills that would have addressed coal ash storage at Plant Scherer stalled.

While Evans is pleased her clients will have access to water in the future, it doesn’t change the impact Georgia Power’s Plant Scherer has had on their lives, she said.

“We are hoping to make our clients as whole as possible,” Evans said. “When you are talking about people’s health and their quality of life being taken from them and their loved ones, there is no way to put that back together.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured