Johnny Isakson, 76, Georgia politician respected by both sides, dies

Johnny Isakson spent his life cutting deals.

From his successful career in real estate to when Georgia’s Republican Party was mostly confined to a small knot in Cobb County to Congress, Isakson learned early on what it took to get two sides to an agreement. And he continued to ply those skills even after the GOP cemented its political dominance in the state, making him a uniquely beloved figure among Democrats and Republicans alike for more than four decades.

Isakson’s motto was a simple one: “There are two types of people in this world: friends and future friends.”

Undeterred by several losses early in his political career, he rose to become one of Georgia’s most popular politicians before stepping down in late 2019 due to declining health.

Isakson, 76, died Sunday morning, according to his family. He had been battling Parkinson’s disease for the better part of a decade.

He is survived by his wife, Dianne, three children and nine grandchildren. Funeral arrangements are still being finalized.

» Share your condolences or view the online guestbook.

In Congress, Isakson helped craft the No Child Left Behind education law and, later, its replacement. He worked to reform the Department of Veterans Affairs, immigration policy and health care.

He was something of an anomaly in hyperpolarized Washington: a conservative willing to work with Democrats and disdainful of shrill rhetoric. He was so internally popular that his Republican colleagues handed him two committee chairmanships when the party took the Senate in 2015.

“If you had a vote in the Senate on who’s the most respected and well-liked member, Johnny would win probably 100 to nothing,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., an Isakson confidant, told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2019. “His demeanor is quite different from what most people expect of politicians.”

At home, Isakson was fond of retail campaigning and small gestures of kindness. He was one of the only GOP officials who would regularly attend the annual Martin Luther King Jr. Day ceremonies at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, and was known to invite Democrats like Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms as his plus-ones to the State of the Union address.

“If all Republicans were like Johnny,” former Gov. Roy Barnes, a Democrat, once said, “I would be a Republican.”

John Hardy Isakson was born Dec. 28, 1944, the oldest son of Julia and Edwin Andrew Isakson, who drove a Greyhound bus and fixed up houses. Growing up in south Fulton, he often heard tales of his grandfather Anders, who emigrated from Östersund, Sweden in 1903 and anglicized his name when he reached the U.S.

A teenaged Johnny spent his summers on his maternal grandparents’ farm in rural Ben Hill County, helping with corn and pecan harvests. He went on to the University of Georgia, where he was fixed up with Dianne and became close friends with Saxby Chambliss, who would later serve with Isakson in the Senate.

Isakson’s first taste of politics was in college when he volunteered for Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign. Goldwater won Georgia that year amid a backlash to civil rights legislation, but Democrats still dominated at the state and local level.

Isakson joined the Georgia Air National Guard and returned to Cobb County to open up a branch of Northside Realty, then a small business run by his father. He climbed the ranks, helping build the company into a real estate empire in the Southeast. He was eventually promoted to company president and became a millionaire. During that time, a local zoning dispute prompted Isakson to start getting more active in politics.

“I ran as a Republican because my two choices to associate myself with were George McGovern and Richard Nixon pre-Watergate,” he told the AJC in 2013. “The obvious choice for me was the guy who was for business and free enterprise and lower taxes and a hawk on defense.”

His first campaign was for Cobb County Commission in 1974. He lost, and not for the last time.

The biggest lesson he learned, Isakson later said, was to directly ask people for their votes.

Isakson won a seat in the state House in 1976, as the rest of the state voted big for Democrat Jimmy Carter. He arrived at the Gold Dome along with fewer than two dozen Republicans.

“You’ve heard about the legendary phone booth” large enough to hold all of Georgia’s Republicans, said Sandy Springs Mayor Rusty Paul, who also got his start in the 1970s. “Well, we had enough room to make a phone call and still hold a meeting.”

Isakson quickly established himself with his small band of Republicans, rising to the minority leader post in 1983 and leveraging his party’s votes whenever Democrats fractured along ideological and urban-rural lines.

“He was very amicable and approachable,” said state Rep. Calvin Smyre, D-Columbus, who was floor leader for Gov. Joe Frank Harris when Isakson was minority leader. “He’s been the same to me whether or not he was in power or out of power, and I think that’s key when you’re consistent with how you carry yourself.”

In 1990 Isakson took a shot and ran for governor, losing to Zell Miller following a nasty and often personal campaign. Isakson was well-funded but was dragged down by President George H.W. Bush’s sinking popularity.

He was back in the game in 1992, winning a state Senate seat. In 1996 Isakson aimed for statewide office again, running for U.S. Senate.

This time, Isakson’s congeniality became a detriment and he was seen as insufficiently conservative. He lost a Republican primary to businessman Guy Millner, who pounded at Isakson from the right on abortion.

At that point, Isakson was ready to hang it up and go back to real estate. Until he got a call from Miller, his former foe, to come to the Governor’s Mansion. The Democrat offered Isakson a job as head of the state Board of Education.

“There’s some kind of trick in here somewhere,” Isakson thought, but he took the job anyway.

Isakson was ready when U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich decided to step down abruptly after the 1998 midterms. In a quick-turn special election in a Cobb County-based district, no one could match him. He arrived in Congress in early 1999.

When Miller, by then a member of the U.S. Senate, stepped down in 2004, Isakson ran to replace him. But the Republican once again found himself in a competitive primary, this time against businessman Herman Cain — who later would have a brief turn as a front-running presidential candidate — and U.S. Rep. Mac Collins.

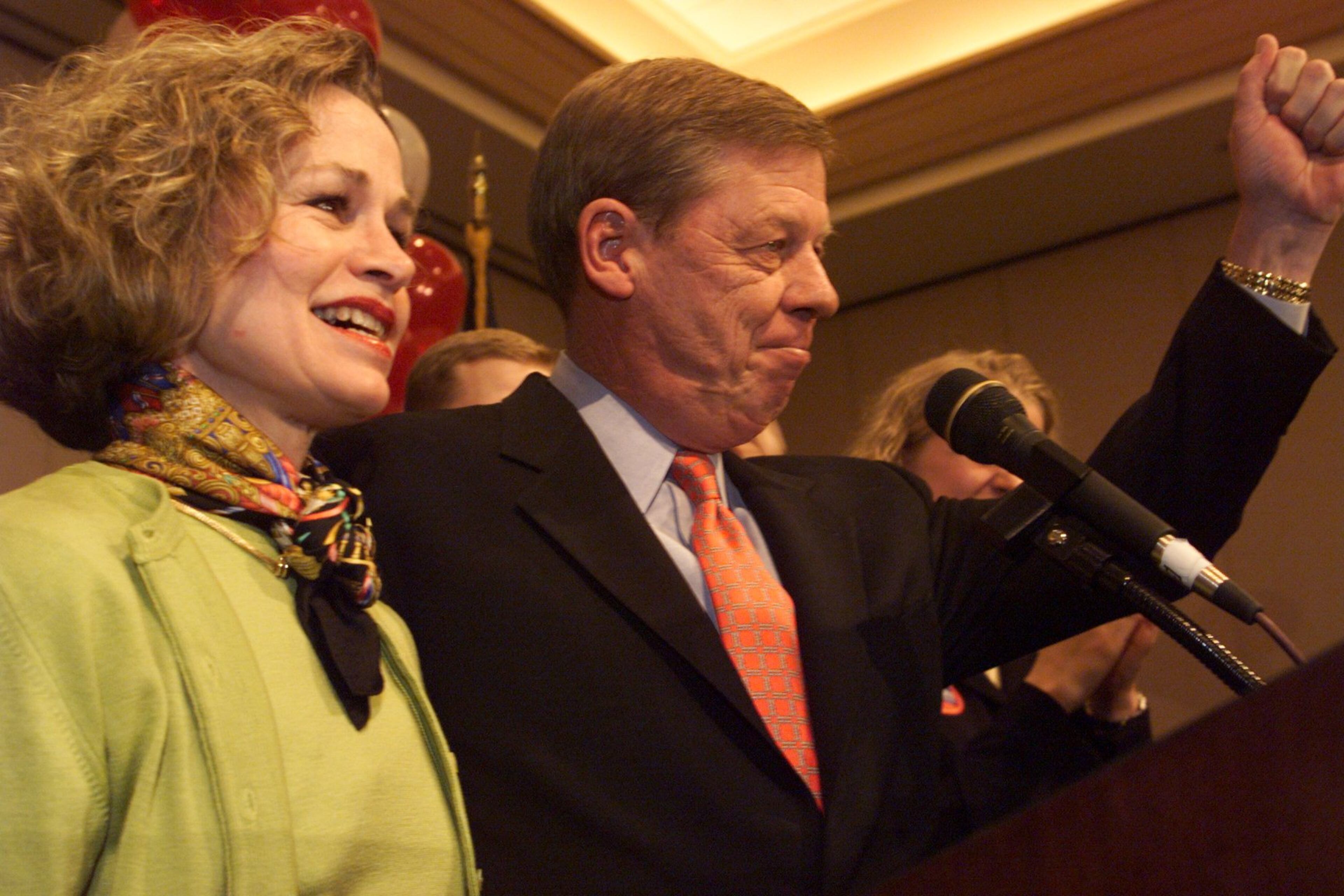

Isakson was again attacked for not taking a harder line on abortion, but this time he shifted his stance, saying he would only support legal abortion in cases of rape, incest or to save the life of the mother. After winning the primary, he romped in the general election against Denise Majette to join the Senate, becoming the only Georgian ever to have been elected to the state House, state Senate and both chambers of Congress.

Isakson’s reputation as a savvy dealmaker was cemented early in his D.C. tenure. He was months into his first Senate term when Delta Air Lines filed for bankruptcy, leaving the pension plans for some 91,000 Georgians on the line.

He quickly got to work on legislation allowing the carrier to stretch out payments on its pension plans. He negotiated with individual lawmakers even as he faced resistance from then-President George W. Bush and powerful congressional leaders who were opposed to special carve-outs for airlines as part of a broader pension overhaul.

Isakson spent months working the issue, taking the unusual step of sitting through closed-door House-Senate meetings despite not being a member of the negotiating committee. In the hours before a final Senate vote, Isakson met with critics late into the night urging them one by one to drop their opposition.

The painstaking work paid off. The final bill sailed through the chamber 93 to 5. Isakson celebrated at home by pouring himself a glass of gin and doing his laundry.

“It was the happiest day of my life,” Isakson recounted. Delta employees later thanked him with a bottle of gin and roll of quarters.

Sometimes, Isakson’s parochial proclivities attracted him negative headlines.

One national newspaper dubbed Isakson “the senator from Delta” for his work on the pension bill. He also received attention for contacting federal agencies on behalf of Parker “Pete” Petit, a longtime donor who headed the Marietta biopharma company MiMedx and was later convicted of securities fraud. An Isakson spokeswoman said at the time that the senator treated Petit’s matter the same as he did all constituent requests and insisted he did nothing inappropriate.

Isakson’s backslapping style was well-suited to the clubby Senate. Isakson formed alliances as he looked for openings to advance state interests such as securing money for the Savannah port deepening or other issues dear to his heart, including compensating U.S. hostages held in Iran at the end of the Carter administration.

His transactional approach won him unexpected allies. When President Barack Obama wanted to reset his icy relationship with Senate Republicans, he called on Isakson to get them together for a dinner.

A fact-finding trip to Greenland to study climate change with California Democrat Barbara Boxer, one of the Senate’s most prominent liberals, forged a friendship that helped Isakson win a water rights fight on Capitol Hill. By that time, Boxer was chairwoman of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, which had jurisdiction over a must-pass water policy bill, and she blocked language authored by Alabama and Florida lawmakers that Isakson had deemed harmful to Georgia.

“He had to make a persuasive case,” said Boxer, who retired in 2016. “But I definitely trusted his explanation of the issue because I knew he was an honest broker.”

During high-stakes policy debates, Isakson was often cryptic about his positions so he had more room to negotiate. That was the case when he huddled with a bipartisan group of more centrist senators in early 2018 during a fight over then-President Donald Trump’s border wall. The group’s eventual immigration proposal, granting a path to citizenship to so-called Dreamers brought to the U.S. illegally as children in exchange for $25 billion in border security money, fell six votes shy of passage.

Even though Isakson’s votes still leaned conservative, some of his biggest critics were on the right — particularly when the tea party ascended as a political force. Some pinned him with the pejorative label of RINO, “Republican in name only.”

Conservatives “want a Navy SEAL representing them; they don’t want Barney Fife,” Atlanta Tea Party founder Debbie Dooley told the AJC in 2013.

After the article was printed, Isakson had a nameplate made up for his office desk saying “Barney Fife” that he promised to deploy next time Dooley visited. He had the good political sense to decline a reporter’s request to photograph him with the plaque.

Chambliss, who often voted in tandem with Isakson when they served together in the Senate, said his friend didn’t move to the ideological center over the years.

“The longer he was in public office, I think the more pragmatic he became — because he was a doer,” Chambliss said. “He wasn’t going to throw bombs. There were enough people to do that.”

When Republicans took over the Senate in 2015, Isakson was tapped by McConnell to lead the Select Committee on Ethics and the Veterans Affairs Committee. The former was a thankless job that required delicate — and often politically awkward — work investigating claims made against colleagues.

The VA assignment pit Isakson against an institution long known for its woes, and one that was hit with a series of scandals both nationally and in Georgia during the Obama and Trump administrations.

It took several attempts, but Isakson eventually hashed out bipartisan compromises to expand private health care options for veterans facing long wait times and expedite the removal of problematic employees at the sprawling federal department.

He at times tussled with the Trump White House on VA care, and quietly killed the president’s nomination of Rear Adm. Ronny Jackson, a White House physician, to head the department after a scandal emerged in the press.

Regardless of Isakson’s efforts, the VA has struggled to keep up with the flood of returning veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan and lingering tales of misconduct.

Despite Isakson’s deal-making reputation, he was also an unabashed party loyalist. He was particularly vocal about his allegiance to McConnell, whose office he would often visit unannounced while the Senate was in session.

His fealty to the party, however, was uniquely tested by Trump’s rise.

Isakson endorsed Trump as he was on the cusp of clinching the Republican presidential nomination in 2016, but he largely kept the real estate mogul at arm’s-length.

Unlike his Georgia colleague David Perdue, Isakson declined to defend many of the president’s more incendiary actions. He was pointedly critical of Trump’s comments following a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the death of U.S. Sen. John McCain.

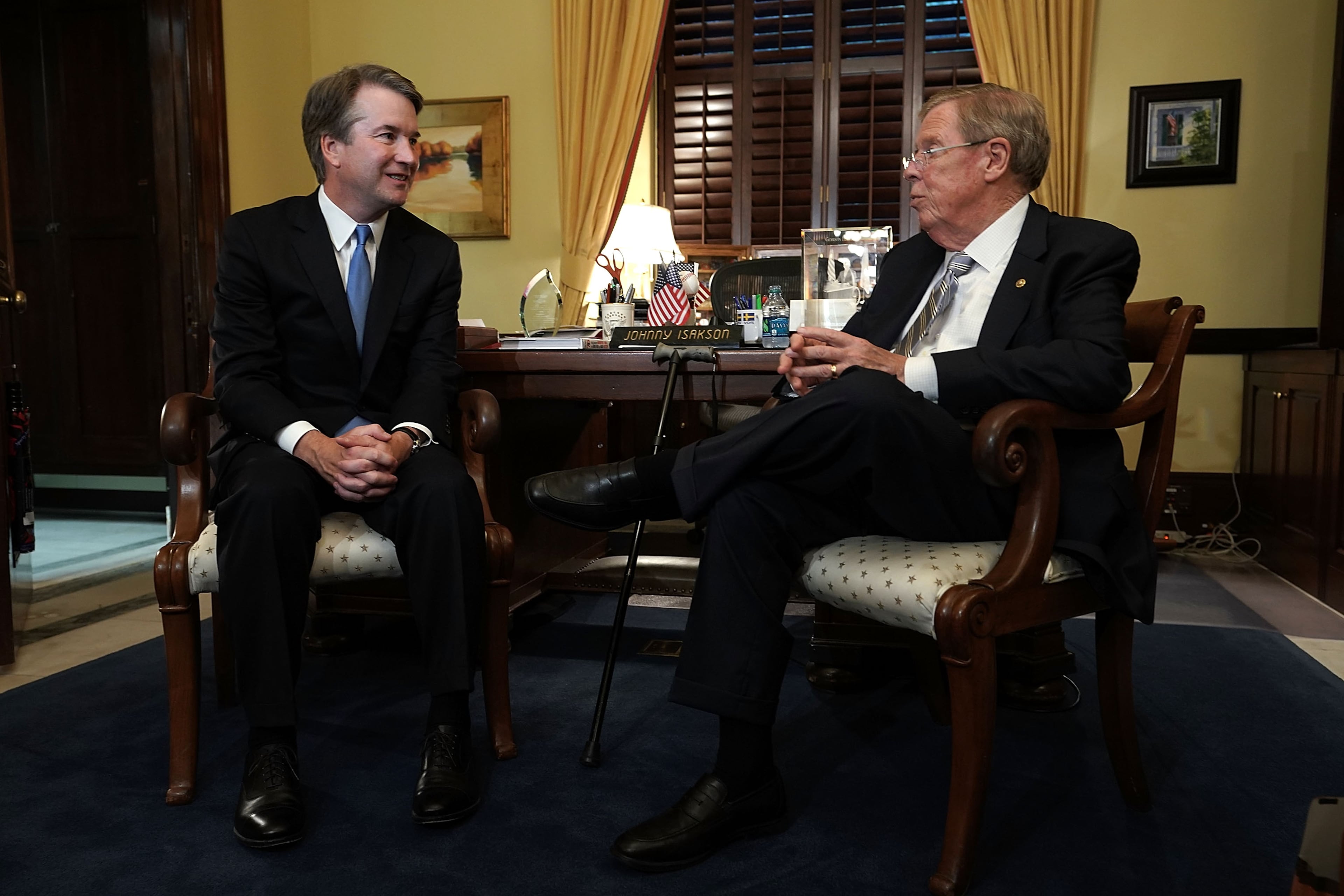

At other times, Isakson worked in concert with the White House. He supported the vast majority of Trump’s initiatives and nominees that moved across the Senate floor, and he voted to confirm Trump’s first two Supreme Court picks, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh.

His approach to Trump and his history of campaigning in communities of color were held up by some as a model for GOP candidates struggling to hold on to their seats in Atlanta’s newly competitive northern suburbs. But even Isakson’s closest allies acknowledged that he was among a shrinking group within the party.

“It’s not the en vogue mentality right now,” said Heath Garrett, Isakson’s longtime political strategist, in early 2019. “It’s easier to just listen to Rush Limbaugh and be the most conservative person and win a really easy Republican district. But I sure hope that there are more Johnny Isaksons out there — and I think that there are.”

Isakson’s schedule slowed little after he revealed in 2015 that he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. The announcement explained his slow, shuffling gait and seemed to rejuvenate the senator, who became one of the most visible people living with the disease. Thank-you’s and disease management tips poured in from around the country.

Eventually, his health problems caught up with him. A cane soon appeared in his hand, and painful back surgeries eventually led to him to traverse the U.S. Capitol in a wheelchair or walker.

In July 2019, Isakson took a fall in his apartment that fractured four ribs and tore his rotator cuff. An MRI revealed that a previous cancerous growth on his kidney had doubled in size.

A surgery successfully removed the growth, but Isakson still concluded he couldn’t finish out his third term.

His retirement announcement stunned the Georgia political world and prompted a behind-the-scenes scuffle for Gov. Brian Kemp’s appointment to the seat. When the governor announced an unorthodox public application process, more than 500 people applied, including current and former officeholders, business executives, a U.S. ambassador and radio commentators.

Kemp eventually selected financial executive Kelly Loeffler for the position. In January 2021, after serving for a little more than a year, Loeffler lost to Democrat Raphael Warnock, the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, whom Isakson had invited to Washington on multiple occasions over the years.

Isakson largely avoided the spotlight after stepping down. He launched the Isakson Initiative to raise money for research into Parkinson’s and other neurocognitive diseases. One of his last major public appearances was in January 2020, when Kemp announced that the University of Georgia was launching a professorship named in Isakson’s honor that would focus on developing treatments for Parkinson’s.

As he wrapped up his more than 40 years in elected office, Isakson made the case for bipartisanship and setting aside egos to solve problems.

“I just hope what everybody will do,” he said in a December 2019 interview, “is look beyond the pettiness of today’s politics … to try and bring us back to some even keel, where we can disagree amicably and agree aptly and solve problems rather than create them.”

An earlier version of this article gave the wrong year in which Isakson’s grandfather emigrated from Sweden.