Before Georgia’s unprecedented hand recount of presidential ballots had even begun, efforts were in the works to discredit it.

While the Trump campaign demanded heavier scrutiny of absentee ballots — followed by a weekend tweetstorm by Trump himself complaining about mail-ins — questions were also being raised about the objectivity of VotingWorks, a nonprofit providing technical assistance to the state.

The Secretary of State’s office hired VotingWorks earlier in the year to provide software and operational support during a legally-required process known as a risk-limiting audit, which is designed to confirm an election’s outcome through a random check of ballots.

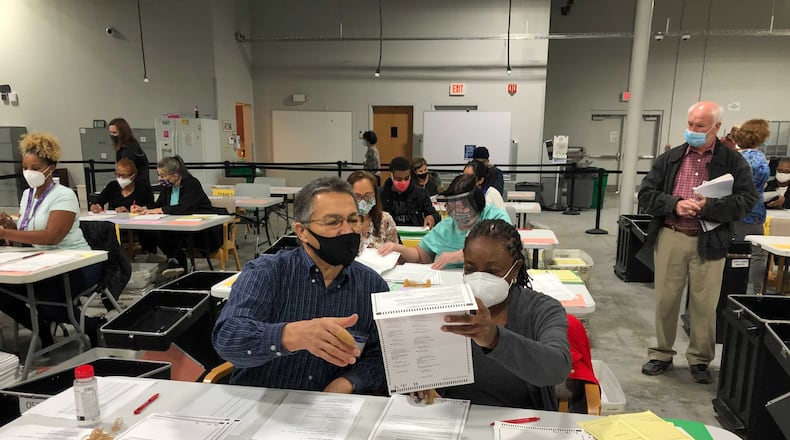

Because of the razor-thin margin in the presidential race, and because of controversy surrounding Georgia’s flip to blue, the audit has evolved into a Herculean ballot-by-ballot recount in all 159 Georgia counties that started Friday and is to be completed by Wednesday midnight.

A San Francisco-based nonprofit, VotingWorks describes itself as nonpartisan and concerned with promoting democracy through improved technology and election security. Two of its officers, however, have donated to the campaigns of Democrats Joe Biden, Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, Elizabeth Warren, Cory Booker and John Kerry.

That opened the company up to Twitter assaults launched last week by Lee Stranahan, a journalist who worked for right-wing Breitbart News and now hosts a radio show for the Russian-government controlled Sputnik news agency. Stranahan criticized the nonprofit’s executive director, Ben Adida, for his donations and calls him “very partisan” for remarks Adida made on a personal blog in 2016 and 2018.

Adida told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution that his personal opinions and political leanings aren’t relevant to his work as an elections consultant.

“Anybody who works with elections is aware of politics and has a political opinion,” Adida said. "If people want to disagree with my personal political opinions, yeah, of course, but I don’t bring them to work.

“If you look at the states that we’re helping, we’re in rural counties in Mississippi, helping bring back the paper ballot,” he said. “Meanwhile, we’re helping audits in Michigan, in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island, which currently are blue states. We’re going to work with any state that cares about election integrity, and our only mission is going to be that.”

Credit: Special

Credit: Special

Gabriel Sterling, who has been managing Georgia’s new voting system, said he is not concerned about VotingWorks officers' take on national politics.

“It is a nuts-and-bolts process. It’s math," Sterling said. “There isn’t anybody else who does this. This is a brand new science.”

Adida also stressed that VotingWorks isn’t conducting the recount itself. That work is being done by audit teams working for county elections offices.

“We do not touch the ballots or count the ballots,” he said. “We provide the operational support, meaning we are there to train folks, we are there to provide documentation, provide the software to help them enter the data.”

In its two years of existence, VotingWorks has earned a national reputation for helping states and counties run risk-limiting audits. Invoices show the Secretary of State’s office is paying the nonprofit $83,000 for its work on the audit, mostly for use of the nonprofit’s software and labor costs for on-call specialists. The money will come from federal grants from the Help America Vote Act.

“We're going to work with any state that cares about election integrity, and our only mission is going to be that."

VotingWorks told the AJC that between its own personnel and helpers it has enlisted from other organizations, it will have about 15 to 20 people on the ground in Georgia during the audit. Another nonprofit involved in the effort is Verified Voting, a Philadelphia-based nonprofit that’s also concerned with voting security and has taken a strong stand in favor of paper ballots.

Mark Lindeman, an interim co-director for Verified Voting working in Georgia, said the process is too transparent for anyone to tinker with the count, even if they wanted to.

“The parties are entitled to monitors in every county,” he said. “I know there are both Democratic and Republican monitors here. They are in a position to confirm that we’re not tampering with the process in any way, any more than they are. We’re just in the room.”

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Trump fuming over mail-ins

The level of access for partisan monitors has been a continuing point of contention for Republicans, who have leveled uncorroborated allegations of fraud at the process that saw Georgia’s electoral votes go to a Democrat for the first time since 1992.

Trump and his campaign have not provided any evidence of wrongdoing. Suggestions that absentee ballots could have been requested and returned by phony voters has become a running theme of the unsubstantiated allegations.

Trump himself took a swipe at Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger in a Friday night tweet, blasting the fellow Republican as a “RINO” who won’t go back and re-check signatures on absentee ballot envelopes for fraud.

“Without this the whole process is very unfair and close to meaningless,” the president tweeted. “Everyone knows that we won the state. Where is (Gov. Brian Kemp)?”

In more tweets on Saturday, Trump railed against a non-existent consent decree approved by Gov. Kemp, apparently referring to a settlement this year between Raffensperger and the Democratic Party of Georgia requiring election workers to consult with two of their peers before rejecting absentee ballots because of possible mismatched signatures.

“What are they trying to hide. They know, and so does everyone else. EXPOSE THE CRIME!” Trump said, garnering another “This claim about election fraud is disputed” label from Twitter.

Trump continued his broadside against the state’s recount on Sunday, tweeting that the effort “is a scam, means nothing,” though there’s no evidence of widespread fraud or irregularities.

The president again highlighted last spring’s legal settlement concerning absentee ballots in Georgia.

In a letter to Raffensperger on Thursday, the day before the recount launched, Trump’s campaign and the Georgia Republican Party complained that the audit process doesn’t include making sure that signatures on absentee ballot envelopes and applications were properly verified.

“Our analysis of your office’s publicly available data shows that the number of rejected absentee ballots in Georgia plummeted from 3.5% in 2018 to 0.3% in 2020,” the letter said. “This raises serious concerns as to whether the counties properly conducted signature verification and/or other scrutiny of absentee ballots. In fact, it presents the issue of whether some counties conducted any scrutiny at all.”

Georgia accepted more than 1.3 million absentee ballots. Rejections declined partly because Georgia law eliminated the requirement for voters to write in their birth years or addresses on ballot envelopes, instead only mandating their signatures.

Sterling, the voting system manager, said the signatures on envelopes were verified by counties on the front end. County elections managers say they matched them against signatures from voter registration applications, signatures on file with the Department of Driver Services, or signatures on applications to receive the ballots.

The envelopes have since been separated from ballots, so while the signatures could be verified yet again, it’s not possible to tell who the person voted for. Ballot secrecy is protected by state and federal election laws.

So doing what Trump wants would have no impact on the result of the recount.

Staff writers Mark Niesse, Chris Joyner and Tamar Hallerman contributed to this article.

RECOUNT COVERAGE

In order to observe this historic undertaking, several of Georgia newspapers are collaborating to provide you with a statewide view. The Athens Banner-Herald, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Augusta Chronicle, The Columbus Ledger-Enquirer, The Macon Telegraph and The Savannah Morning News will share their collective work with you until the recount is complete.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured