Home for the holidays

» Read more from this series on our Personal Journeys page, which includes some of the best stories from this award-winning series, along with video and photos. You can also find it by typing myajc.com/personaljourneys into your browser on your desktop, laptop, tablet or smartphone.

Next week: We revisit past Personal Journeys to see how those featured have fared.

Christmas Day was always standing room only at my grandmother’s tiny, white house in Charlotte, N.C. She shared it with my great grandmother, who we called Granny, and it was plenty big for just the two of them. But Granny had 11 surviving children, and on Christmas afternoon, most them would gather there, along with their children and grandchildren, all dressed in their Sunday best.

As a child, I felt very small in that crowded house full of grownups, and I spent most of my time prowling for a spot to perch where I would be out of the way.

There were two bright spots for us kids. One was Granny’s lemon pound cake. My mother tried to replicate it once, but Granny never measured anything when she baked so it was a disaster. The other highlight was plucking the envelopes bearing our names from the silver tinsel Christmas tree in their small, dark living room. Inside the envelopes were half-dollars for the little ones and silver dollars for the teenagers. This was the ’60s, and even then it wasn’t much money — no more than what my mother might give me for the ice cream man.

But there was something deeply satisfying about the ritual of it: the white envelope bearing my name written in script; the red ribbon that secured it to the tree; the scissors used to snip it from the branch; knowing exactly what it contained.

We left Charlotte for Columbia, S.C., when I was 9, and we rarely made it back for Christmas Day after that. Although I did go back one last time and get that bump in pay. After Granny died, the tradition stopped.

At the time, I imagined the tradition preceded Granny and that it would continue after she died. I assumed that was the point of tradition, to sustain the familiar and constant in a world that — especially to a child — seemed random and unpredictable.

It has taken a lifetime of ups and downs and ins and outs to appreciate the folly of that presumption. It’s only now, in my fifth decade, that I understand the true meaning of tradition.

Columbia was just the start of our family’s relocations as we followed my father’s climb up the corporate ladder.

After a few years in Columbia, we went back to Charlotte for a year, then to Puerto Rico for a few years, and then Atlanta. Along the way we picked up and dropped Christmas traditions as we went.

In Columbia, there was the Governor’s Carolighting. My mother would bundle me and my three siblings up in coats and hats and take us downtown to the Statehouse where a dozen or so choirs would gather to sing carols before the switch was thrown on the enormous Christmas tree trucked in for the occasion. In Puerto Rico, I celebrated Three Kings’ Day with friends on Jan. 6 with a rustic meal of roast pork and and rice pudding. In Atlanta, there was the tree lighting at Lenox Square. But by then, my siblings and I were growing up and going our various ways. My mother had retired from trying to round us up for group activities.

So once I married and had two sons, I decided to start my own Christmas traditions. I imagined my kids looking back happily on their childhoods as they recalled picking out the tree their father cut down and decorating it to the strains of Bing Crosby on the stereo. I hoped one day they would pass down to their own children our traditions of decorating a gingerbread house and going to the theater to see productions of “The Nutcracker” and “A Christmas Carol.”

Being a traditionalist, my traditions were, well, pretty traditional. My older brother and his wife were more creative. One of their holiday traditions was the gift of new pajamas exchanged the day before Christmas so everyone in the family could wear them to bed on Christmas Eve. I considered adopting it for my own family but ultimately decided against it. I knew it always would be their tradition, not ours.

Once my little family had dispensed with our Christmas traditions, we would go to my parents’ house for Christmas dinner, which was always a repeat of the Thanksgiving Day meal. This was a favorite part of the holiday for me, a chance to experience the last remaining Christmas tradition of my childhood.

But then a curious thing happened. My mother got fed up with turkey and dressing and pecan pie. She decided to start a new tradition: a cross-cultural menu of standing rib roast, Yorkshire pudding and tiramisu. She was the one preparing it, so who was I to argue? Besides, it tasted delicious. But when she tried to move the meal from Christmas Day to Christmas Eve, I put my traditionalist’s foot down. She eventually acquiesced.

I wasn’t completely averse to new traditions, though. I embraced the one in which my father served a round of pre-dinner Bloody Marys. Nothing put the merry in Christmas like a few spirits, and it was the perfect accompaniment to my mother’s famous Cheese Pennies.

The first realization that perhaps I placed too much emphasis on holiday traditions occurred the year my 10-year-old son got sick on Christmas Eve. My parents were back living in Columbia by then, so we stuffed the car’s trunk and package shelf with suitcases, coats, gift-wrapped presents, Christmas stockings and tins of cookies before pointing the car toward I-75 and the four-hour drive east from Marietta. It was late in the afternoon and it would be well after dark before we arrived, but when we woke up the next morning it would be Christmas Day.

“I feel sick,” Derrick said as we pulled onto the interstate.

“What kind of sick?” I asked.

“Throwing up sick.”

“Pull over!” I said to my husband.

Once we stopped, I helped Derrick out of the back seat just in time. Cleaned up and strapped back into his seat, he said he felt better and we hit the road again.

“Just a fluke,” I said to my husband, as he merged back onto the interstate.

“I’m gonna throw up again!” Derrick announced moments later.

There was nothing left to do but go back home, unpack the car and have Christmas in our own home. It was a disappointing turn of events but not tragic — except to Derrick’s little brother.

“You ruined Christmas!” Drew shouted.

That line has become lore in our family. But at the time, I had to remind everyone — including myself — that Christmas would go on whether it happened the way it always had before or not.

As it turned out, Derrick was better the next morning and we made it to Columbia in time for Christmas dinner with the extended family as planned. But it gave me pause. I began to suspect my rigidity about tradition had come to overshadow the admittedly secular reason I loved the season: spending time with family and expressing our love in ways that usually involved trips to the mall and hours in the kitchen.

Our Christmas traditions got more complicated when I got divorced and the kids started splitting the holiday between my house and their Dad’s. I billed it as “two Christmases!” but I don’t think they bought it. They were teenagers and not interested in gingerbread houses and “The Nutcracker” any more. Besides, we were all in a bit of a blue state back then. We pared down our Christmas traditions to the basic gift exchange and festive meal.

And although my sons and I had never been churchgoers, we started attending the candlelight service with my parents because nothing thrilled my mother more than having her family around her in that sanctuary on Christmas Eve.

Eventually I began to realize that the tradition I’d been trying to create and preserve all those years had nothing to do with Christmas trees and gingerbread houses and white envelopes bearing my name. As traditions came and went over the years, there had been only one true constant. The gravitational pull at the nexus of all those holiday trappings had always been our family.

Getting the family together was the tradition. It didn’t matter whether it was for a meal, a church service or “The Nutcracker.” It was the act of crossing miles and political differences, of forgiving past slights and transgressions, of putting the demands of daily life on pause long enough to reconnect and celebrate the people who knew us best and longest.

I’ve definitely loosened up with the traditions over the years. I still put up a tree and stuff stockings for my sons, although they’re grown now. But one year we went to a Korean barbecue for Christmas, another year we went to the Four Seasons. Sometimes my sons and I have Christmas with the extended family, and sometimes it’s just the three of us.

If you asked my sons, their favorite Christmas memories would probably include the time we saw “Edward Scissorhands” at the movie theater. They’d also likely mention the time I accidentally ignited a small fire on the coffee table with a pine-scented candle and a sheet of tissue paper. The memory of us blithely hanging ornaments on the tree unaware of the flames licking the air behind us still cracks us up, only because it didn’t end in disaster.

This year is the first Christmas without my mother, who died in April. Her absence will be a hole in all our hearts this holiday season. I hope someone in the family makes Yorkshire pudding and tiramisu in her memory. But it won’t be me.

This year Derrick and I will go to Los Angeles to spend the holiday with Drew, who lives there now. There’s talk of Thai food and a walk on the beach on Christmas Day. My father considered joining us, but he opted to spend the holiday with my siblings and their progeny in Columbia.

So we’re scattered this year. But in small pockets, on both sides of the country, our family will gather together and celebrate in ways both new and familiar.

In other words, just another traditional Christmas as usual.

About the reporter

Suzanne Van Atten joined the AJC in 2006. As features enterprise editor, she assigns and edits content for the Sunday Living & Arts section, including book reviews, arts features and Personal Journeys. She is also a creative writing instructor and travel book author. Previously Suzanne was arts and entertainment editor for Creative Loafing Atlanta and the Marietta Daily Journal.

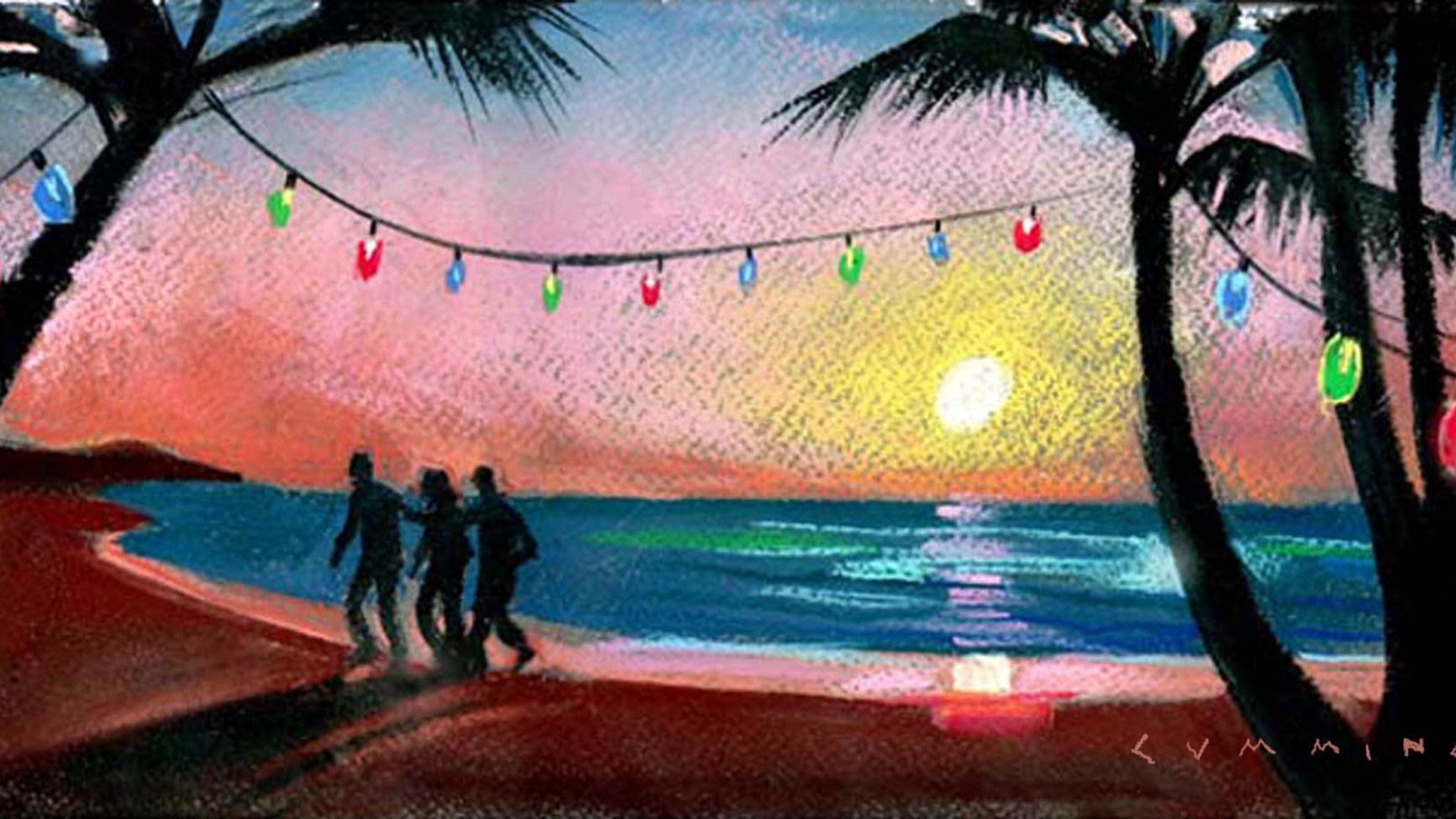

About the illustrator

Walter Cumming is an award-winning illustrator who was on staff with the AJC for 28 years. Cumming studied illustration at the Rhode Island School of Design and received a bachelor's degree in science from the University Wyoming. Since leaving the AJC in 2008, Cumming has had four solo shows and assignments in Spain, France and Germany.