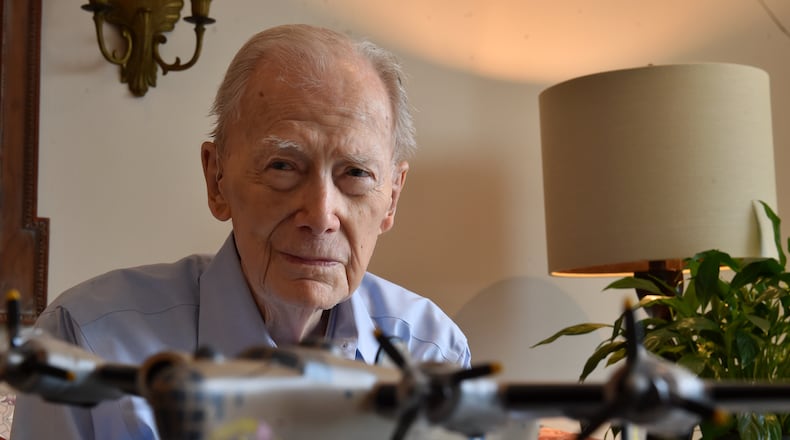

F.C. “HAP” CHANDLER

Age: 94

Residence: Sandy Springs

Service: U.S. Army/Air Forces, navigator, 8th Air Force, 489th and 491st Bomb Groups

Eager to become a combat veteran after arriving in England two months after D-Day in 1944, F.C. “Hap” Chandler Jr. got his first taste of the unfriendly skies of Europe while making a bombing run to a German city named Magdeburg.

“I had a little window, and I looked out and I saw bursts of flames, parachutes, airplanes exploding, and I looked at the temperature gauge and it said 40 below zero. And I said, this is a heck of a place for a Georgia boy. I can’t say I was scared to death. I was really very curious. It was like something you’d see in a movie.”

Chandler, who grew up in Toccoa, was a B-24 navigator on that mission and 34 more during World War II. He was part of 18 missions with the 8th Air Force’s 489th bombardment group and 17 with the 491st, 11 of those as part of the lead crew.

By the time the war ended, Chandler would make five more trips to Magdeburg, a strategic American target because of its oil refinery and tank factory. The last time he went there was March 3, 1945, on his 35th and final mission.

He described it as his most terrifying experience during the war – maybe because it was also the first time he had seen a jet.

“They were all over us that day and shot down several bombers. I remember them coming through our formation. It was hard to hear any sound up there with those four engines going, but it went whoosh, and my gunner said, ‘What was that?’ It was a German jet. We were attacked by jets, by conventional fighters … it was about the most concentrated aerial attack I was ever in. I thought my time might have come, to tell you the truth.”

Chandler survived that German assault, but he wonders what might have happened had the enemy deployed the jets earlier.

“If they had had those in quantity the year before, they might have put a stop to our bombing campaign. We had nothing to contend with them.”

In between those two memorable flights, Chandler recalled his 12th combat mission on an aging plane he said probably should have been out of service by that point. The navigator’s station was on the flight deck, instead of where it usually was right behind the nose.

“We just got ourselves all shot to pieces. I think I counted a couple hundred holes in the airplane. … A piece of shrapnel had come through the nose of our airplane, and had I been standing where I normally would have at the desk in the nose, it would have probably cut me in two or at best just ripped out my stomach. So I would have been killed instantly. But thanks to the good Lord and my mother’s prayers, I was in another position in the airplane. I had some other close calls, but that was as close as I ever came to being killed.”

That’s coming from a man who, after leaving the service and graduating from the University of Georgia in 1947, was called back to active duty in the newly minted U.S. Air Force and sent to Korea for yet another war. This time he served as a navigator and bombardier, flying 50 combat missions, mostly at night.

But for all of his military accomplishments – he retired in 1970 as a lieutenant colonel – he’s most proud of his involvement with the 8th Air Force. When he talks about it today, he speaks in reverent tones.

“It was an elite organization, and it was an honor to serve in it. We had a mission to accomplish and we did it in spades. … And I was a small part of it.”

On one of those occasions, his crew had a chance to lead it.

On what Chandler estimated was his 26th or 27th mission, they were one of about 1,200 U.S. bombers heading for their target in Hanover, Germany. They were serving as the deputy lead plane when the lead plane had mechanical problems and had to pull out of formation. Chandler’s crew took over the lead spot and completed its bombing run, then turned back for home.

“It’s a sight I’ll never forget. We passed squadron after squadron after squadron as they went into the target. A sight that will never be duplicated.”

By the time Chandler made that final treacherous trip to Magdeburg, he said he had a feeling the Germans were close to defeat. His stay in Europe ended when he boarded a ship the day after V-E Day, still scratching his head about how it all came to this point.

“Germany was the most literate country in Europe. … yet they let a jerk like (Adolf) Hitler take it over. And he, under the guise of bringing back prosperity, re-armed and almost conquered the world. It took a tremendous effort to defeat him.”

But the war in the Pacific wasn’t over, and Chandler knew it. So after being home for 30 days, he was selected for pilot training at Maxwell Field in Alabama. He said the 8th Air Force was slated to go to Okinawa to fight the Japanese.

“If the war had lasted, and if I had finished pilot training, I would have been back in the Pacific theater. And I’m very happy I didn’t go because that was a different kind of war. The Germans were bad enough, but the Japanese were absolutely unbelievable.”

Chandler was home in Toccoa on leave, walking around the courthouse square in September 1945, when he said cars started going past him, blaring their horns. That’s when he knew the war was really over.

“Thank God for the atomic bomb because had we had to invade Japan, it would have made Normandy look like a Sunday school picnic. The Japanese were prepared to fight to the bitter end, every man, woman and child. The atomic bomb ended that.”

After the war: Choosing a career in the military over the ministry – he attended Bible college in Wheaton, Ill. – Chandler worked for a company that bought airplanes. He also lived in the Philippines for a short time in the late 1960s. But his family persuaded him to move home to Georgia in 1970, after which he worked in real estate and as a contract engineer.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured