Grace and gridiron

Next week: Three boys transform the life of a childless, middle-aged couple.

ATTRACTION

College Football Hall of Fame

250 Marietta St., Atlanta. $19.99 adults; $17.99 seniors 65 and older, active duty military and students; $16.99 children 3-12. Sunday-Friday 10 a.m.-5 p.m., Saturday 9 a.m.-6 p.m. 404 880-4800, www.cfbhall.com.

For Terry LeCount, the huddle is a familiar environment.

He led huddles as the starting quarterback at the University of Florida in the 1970s and participated in them as a wide receiver in the NFL for seven seasons.

But this one — an impromptu huddle in the Georgia World Congress Center last July — was unlike the others. Gone were the helmets and shoulder pads and grizzled men. This huddle was comprised of women and church elders.

Employed as an aide at Oakhurst Elementary School in Decatur, where his influence far exceeded the title “paraprofessional,” LeCount was pursuing a new vocation — one that would reunite him with his lifelong love affair with the game that had given him so much. He was applying for a job as a fan ambassador with Atlanta’s College Football Hall of Fame.

After his interview at the World Congress Center — during which LeCount told his interviewer "I need to be here" — he ran into Mary Mack, the elementary school principal for whom LeCount had worked for almost a decade. She was attending a convention with members of her church, and when she learned what her colleague was up to, she rounded up her church elders and along with LeCount and his wife, Valjean, the group prayed he would get the job.

LeCount might not be the most church-going individual, but he possesses a powerful belief in God. It was his faith in a higher power that helped him beat the drug and alcohol addiction that derailed his football career so many years ago.

Whether it was his interview skills or the power of prayer that did it, LeCount will never know, but he landed the job.

“All this was meant to be,” said LeCount, 58, looking around him at the hall, a building he likens to a giant library. “I can talk about this all day, man. This is an amazing place.”

2

Rise and fall

One of six children and the oldest son of James and Ruth LeCount of Jacksonville, Fla., Terry LeCount grew up in a neighborhood full of future college and professional football players.

He was such a fast runner, during the 1973 Florida high school track and field state championships, he fell down twice in the 400-meter race and still won with a time of 48.6 seconds. One of his great regrets is that football prevented him from trying out for the U.S. Olympic track and field team.

Instead, he earned a scholarship to the University of Florida in 1974 to play quarterback, a position black players had difficulty breaking into in the NFL as late as the 1980s. His sophomore year, he helped lead the Gators to a 9-3 record and a tie for second place in the Southeastern Conference.

LeCount’s career with the Gators would pave his way for a career in the NFL, but it also sowed the seeds for one of his life’s great battles. After his senior season ended, LeCount went to an off-campus party and tried cocaine for the first time. It was 1977. Eric Clapton’s hit single that year was called “Cocaine,” and the drug was ubiquitous on the club and party scene. It was like nothing LeCount had ever experienced before, and it would end up haunting him for the next 15 years of his life.

In the NFL, LeCount became a wide receiver. He was drafted by the San Francisco 49ers and early in his second season was traded to Minnesota, which soon became home.

His best pro season was 1981 — an era when teams threw the ball far less than they ran it. He caught 24 passes for 425 yards and two touchdowns. That season against the San Diego Chargers and their famed “Air Coryell” offense, LeCount totaled six receptions for 120 yards and two touchdowns. After he caught the game-winning touchdown pass, he spiked the ball in the end zone — a no-no under disciplinarian Bud Grant, Minnesota’s hall of fame coach. LeCount walked past Grant after the play, expecting a tongue-lashing. Instead, Grant gave him the game ball in the locker room during his post-game speech.

Life as an NFL player was good, and LeCount and his teammates liked to party. A night on the town often meant going to Maximilian’s, a club owned by former Green Bay Packers wide receiver Max McGee, a notorious playboy during his career in the ’60s. LeCount was not alone in his enthusiasm for the nightlife, as the large majority of the Vikings’ players would attend those gatherings until last call at 1:30 a.m. In 1987, LeCount’s quarterback, Tommy Kramer, would enter rehab following an arrest on drunk driving charges.

In the days before social media and TMZ Sports, pro teams had spies to keep tabs on players, and Grant knew his players’ bad habits. One day he called LeCount into his office and gave him a warning.

I know what you're doing out there, Grant told LeCount.

In 1981, the Vikings started off 7-4 but lost their final five games. LeCount convinced himself his late-night habits didn’t affect his performance, but in retrospect he knows the drinking and partying contributed to the team’s late-season slide.

The Vikings continued to have mediocre seasons. In 1984, before the team’s second game of the season, coach Les Steckel took LeCount aside and told him he wouldn’t start in the game against Philadelphia. In fact, LeCount didn’t play a snap.

The next day when he reported to the practice facility, he noticed his teammates’ long faces as he approached his locker stall. It had been cleared out, and a trainer told him Steckel wanted to see him. LeCount was cut from the team. No other team offered him a contract. At 28, his career had ended and he had little to show for it. Back then, NFL players didn’t earn the riches they do today. LeCount started out earning an annual salary of $35,000. The most he made was $80,000 a year.

With his NFL days behind him, LeCount discovered that the people he thought were his friends — namely former teammates — didn’t have time for him anymore. To them, LeCount represented a cautionary tale. Just as his career was ending, so was his brief marriage. His ex-wife moved to Philadelphia, taking their newborn daughter with her.

LeCount would not gain sobriety for eight more years.

3

Hard-earned recovery

LeCount moved to San Francisco in 1990, thinking the change would revitalize his post-NFL life. But the move did not alter his behavior when it came to drugs and alcohol. During the day, he sold orthopedic running shoes and worked as an aide at a middle school. At night, he got high and isolated himself in his downtown apartment on Sutter Street.

Every addict is chasing his first high, LeCount says, and his endurance was beginning to flag. He owned a record by comedian Richard Pryor, a famous addict himself, and LeCount listened to it often. He related to a bit Pryor did on addiction in which the comedian described the drugs as taunting him to “come on, use me.”

LeCount was tired of the dope talking to him. He would go two or three days trying not to use, maybe a week, but he would eventually give in. He tried rehab, but it didn’t stick. He vividly remembers the day it finally did. April 17, 1992. He skipped work and walked the city on a cloudless afternoon all the way through the night.

Back in his apartment, LeCount said God put him on his knees and he cried like he’d never cried before.

“I knew that was it,” he said. “I just knew it.”

Today LeCount rises at his Riverdale home every day at

3:30 a.m. In the cozy ranch he shares with his wife, Valjean, he turns to his favorite dog-eared passages in Alcoholics Anonymous literature with titles like "The Language of Letting Go" and the "Big Book." If the weather is cold, LeCount starts a fire in his wood-burning stove.

Sometimes he prays, but mostly he meditates. He calls it his “quiet time.”

It wasn’t always that way. Ninety days into his sobriety, LeCount was eager to receive a three-month chip at his AA meeting. The tokens are handed out to commemorate milestones of sobriety, but on this day they had run out of three-month chips.

LeCount was furious. He felt cheated. His sobriety was still precarious. He would show them. Just then an older member reached into his pocket and pulled out his own three-month chip. He gave it to LeCount. That act of generosity, combined with the tangible proof of his hard work, stopped LeCount cold. The chip remains among his most treasured possessions.

Four years later, temptation tested him again. He was getting money out of an ATM when he heard a familiar voice. His spine went cold. It was his old drug dealer.

At that moment, LeCount heard what he calls his “higher power” speak to him. “It said, ‘Go on over there and talk to him,’ ” he recalls.

LeCount remembers the dealer talking, but he doesn’t remember the man’s words.

He heard the voice again. This time it told him to walk away.

I told you, it said. You made it. Your desire is gone.

4

Newfound passion

Shortly after LeCount’s NFL career ended, a friend had suggested he use his résumé as a former Viking to land a job helping out at a local middle school. He discovered he liked the work, and he was good with kids.

His first job was as an aide to a special education teacher. His duties included providing informal security when the teacher made home visits to a rough neighborhood in the Twin Cities area. The teacher advised him of the students, They’re smarter than you. Be tough on them.

Later he was assigned to an older teacher who warned LeCount that educators in administrative positions often lose touch with the kids. I like being in the dirt, she told him. When you're in the dirt, you make a difference.

LeCount took those words to heart. At the University of Florida, he had finished 20 hours short of a degree in speech communications. Through the years he’s been encouraged to go back to school and finish his degree, to get certified as a counselor. LeCount always refused. He liked being in the dirt. He liked seeing the impact he had on children’s lives.

In 2002, LeCount reconnected with a college sweetheart, Valjean, who lived in Atlanta. He joined her here and married her the following year.

Again, his football life opened doors for him when he needed it. He applied for a job as a substitute teacher at Renfroe Middle School with the City Schools of Decatur. The assistant principal remembered LeCount from their days playing youth football together in Jacksonville.

LeCount’s good-hearted nature gained him popularity among the students and faculty, and his reputation carried its way to Mary Mack, principal at Oakhurst Elementary School. When LeCount interviewed for an opening as a paraprofessional in kindergarten, Mack hired him on the spot. She was drawn to “his passion for learning, his passion for life, his passion for people,” she says.

At Oakhurst, LeCount played myriad roles. As the first member of the faculty to arrive each day, he would wait with children whose parents dropped them off outside the building before it officially opened at 7:30 a.m. He maintained order in the cafeteria, where students who arrived early were sent to wait for class to begin. At the end of the day, he assisted with the carpool line.

In addition to his job at Oakhurst, LeCount worked at the Samuel L. Jones Boys & Girls Club in the afternoons. On weekends, he started a fitness training bootcamp for adults and co-founded a mentoring group for African-American boys.

Through the years he’s touched the lives of many children, but there’s one in particular of whom LeCount is most proud.

Now a fifth-grader, LaBron Foy is the baby of his family with siblings who are 30 and 18. LeCount first met LaBron when he was in kindergarten. He was big for his age. Not chubby, but big enough to stand out. And he cried easily and often. His parents were very protective.

Every year LeCount gave the kindergartners the same message on their first day: Your mom and dad are gone. If anybody bothers you, I will protect you. Making the children feel safe was LeCount's first priority.

One day it was time to catch the after-school bus for the Boys & Girls Club, but LaBron refused to get on. LeCount had to physically put the child on the bus, but he reassured the boy he would meet him later at the club.

At the Boys & Girls Club, LeCount discovered LaBron was insecure when it came to athletics. He was afraid of catching a football, so LeCount taught him how. He had poor running form, so LeCount instructed him in the proper technique. LeCount showed LaBron how to operate the scoreboard at basketball games. In the classroom, he taught him to take roll call. And he taught LaBron to stand up for himself when squabbles with other children inevitably arose.

LeCount saw many of his lessons start to take hold as LaBron transitioned to first grade, but it was in third grade that LaBron really began to demonstrate what he’d learned from LeCount.

After attending a dance performance with his class at Agnes Scott College, LaBron took it upon himself to organize a similar production at Oakhurst for Community Circle, an event held on alternate Fridays to showcase students’ achievements. LaBron recruited fellow classmates and they practiced during recess. At the performance, the children moved to the beat of salsa music and concluded with the boys scooping the girls up and carrying them off their makeshift stage. Then each girl was presented with a rose. LeCount and LaBron’s mother exchanged looks of amazement.

That same year, LaBron and LeCount collaborated on a segment about Black History Month for the school’s morning news broadcast. In an unscripted moment, LaBron signed off by thanking LeCount for being his “mentor and life coach.”

LaBron now attends Decatur’s 4 / 5 Academy at Fifth Avenue, where is he is captain of the patrols.

“He could probably do anything he puts his mind to,” LeCount says of LeBron. “He’s going to be one of those in leadership, running the show.”

5

Home field advantage

Who would be better to work at the College Football Hall of Fame than you?

That was the question Valjean put to her husband one day. She understood how much he loved the kids in Decatur and how often his green pickup truck was recognized when they were in the neighborhood. She saw how eager parents were to stop and talk to him. But she knew how much the game still meant to him after all these years.

In many ways, LeCount’s new job at the College Football Hall of Fame is not so different from his old job. One Saturday morning last month, LeCount was working in the hall’s “Skill Zone,” helping fans, mostly children, attempt to kick a short field goal. When the same two boys kept coming back time and again, LeCount stopped them.

“Where’s your dad?” he asked.

“Upstairs,” they answered.

“Y’all should know stuff up there. You can’t live all day here. What Hall of Famer do you know? Did you know there’s 948 Hall of Famers in here?”

He continued to pepper them with questions.

“Do you know who Archie Griffin is? He’s the only two-time Heisman winner. Nobody’s ever done that. Let me show you something.”

He pulled the boys back and positioned them so they could see upstairs where Griffin’s uniform is displayed.

“See that jersey? That’s No. 45, that’s him. The only one!”

Then he said, “Did you know I’m in the hall?”

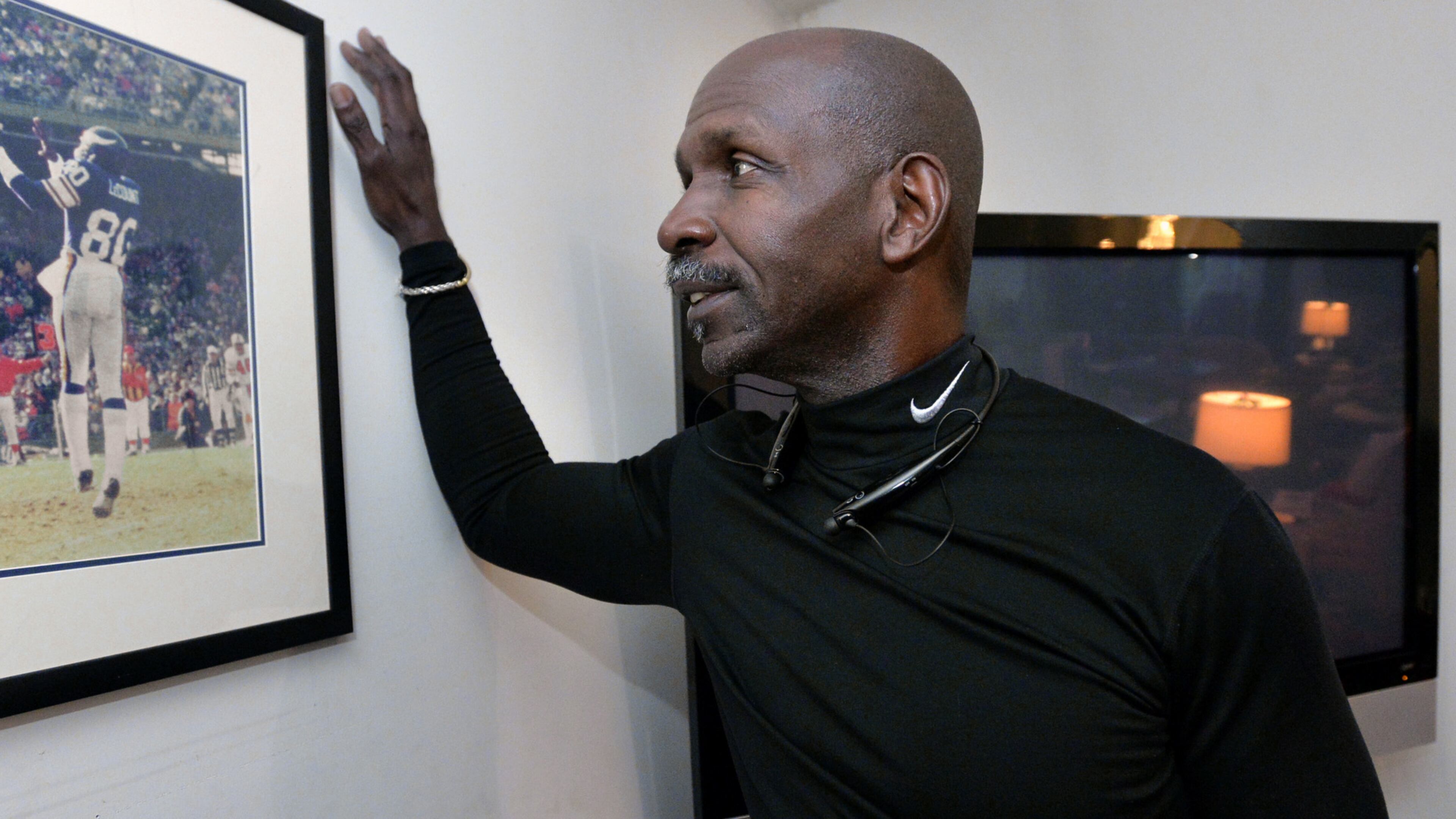

Poking around one day in the interactive galleries for Hall of Fame inductees, LeCount had pressed a touch screen to view a film highlight and noticed he was in the clip for Florida State linebacker Ron Simmons.

He gave the boys an assignment. He told them to go to the third floor and watch the video clip. He told them he was No. 7 in the blue jersey getting sacked. Then he quizzed them again to make sure they remembered the information.

“What school? What player?”

The boys responded correctly.

“Come back and see me when you’re done.”

They did and one of them, a left-footer, booted a kick high and true through the uprights.

Later, LeCount spent time in the “quad,” where first-time visitors enter unsure of where to go. He took good-natured jabs from Georgia fans who noticed his Florida Gators lanyard. He joshed with a group of men wearing Pittsburgh Steelers garb and joked that one of the larger ones was Steelers center Maurkice Pouncey. He advised visitors to start on the third floor with the galleries and work their way down.

Sometimes he spotted familiar faces among the visitors. Working at the hall has given him the opportunity to reconnect with old friends and ex-teammates who visit. Last fall he encountered Steckel — the NFL coach who ended his career — and the two men warmly embraced.

LeCount implored visitors to watch the 10-minute film about what makes college football great. Pageantry, roaring crowds and bone-chilling hits explode off the screen. It’s the kind of experience that leaves a sports fan with goose bumps. LeCount has his own favorite part. Two LSU players are sprinting down the field to cover a kickoff. Their arms pump in unison, exemplars of flawless technique.

“When I see that,” LeCount said, “I want to suit up.”

HOW WE GOT THE STORY

Freelance writer John Manasso first met Terry LeCount in 2007 when LeCount was the paraprofessional for Manasso's son's kindergarten class at Oakhurst Elementary School in Decatur. Manasso witnessed how LeCount nurtured children who occasionally needed a helping hand, including Manasso's son at times. Three years later, LeCount was the paraprofessional for Manasso's daughter's class. When news spread last summer that LeCount had left Oakhurst for the College Football Hall of Fame, Manasso set out to find out why and to chronicle the arc of LeCount's life, which has had many fascinating chapters. It is an inspiring story about redemption and second chances.

Suzanne Van Atten

Personal Journeys editor

personaljourneys@ajc.com

About the reporter

John Manasso worked as a staff writer at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution from 1999 to 2007, covering the city's now re-located NHL franchise, the Thrashers. In 2005, he wrote a book about the death of Thrashers player Dan Snyder, "A Season of Loss." He is a freelance writer who has written for FoxSportsSouth.com and NHL.com.

About the photographer

Hyosub Shin was born and raised in South Korea. Inspired by the work of National Geographic photographers, he came to the United States about 10 years ago to study photography. Past assignments include the Georgia Legislative session, Atlanta Dream's Eastern Conference title game, the Atlanta Air Show and the Atlanta Braves' National League Division Series.