Georgia explores wastewater testing to predict COVID-19 outbreaks

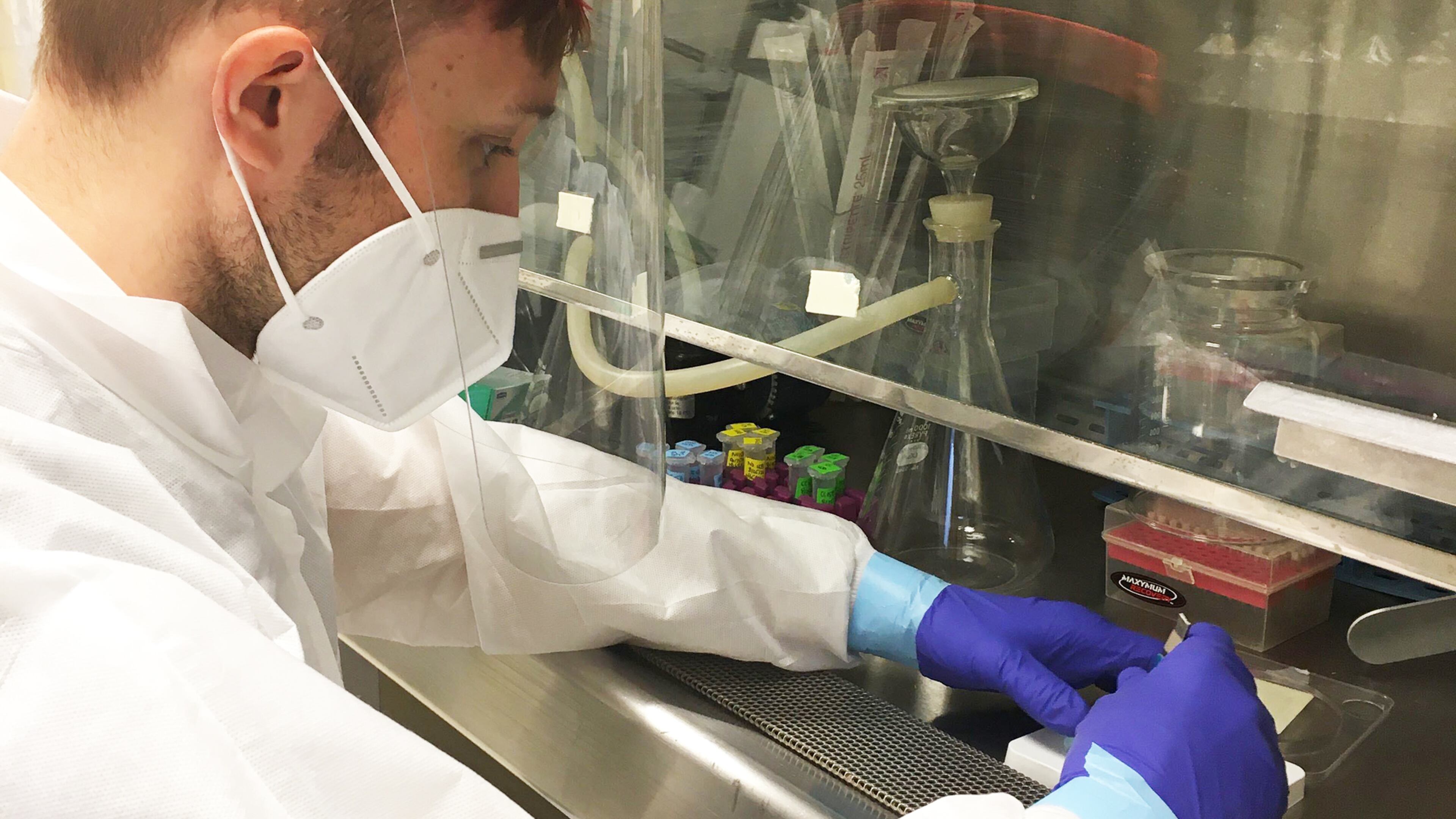

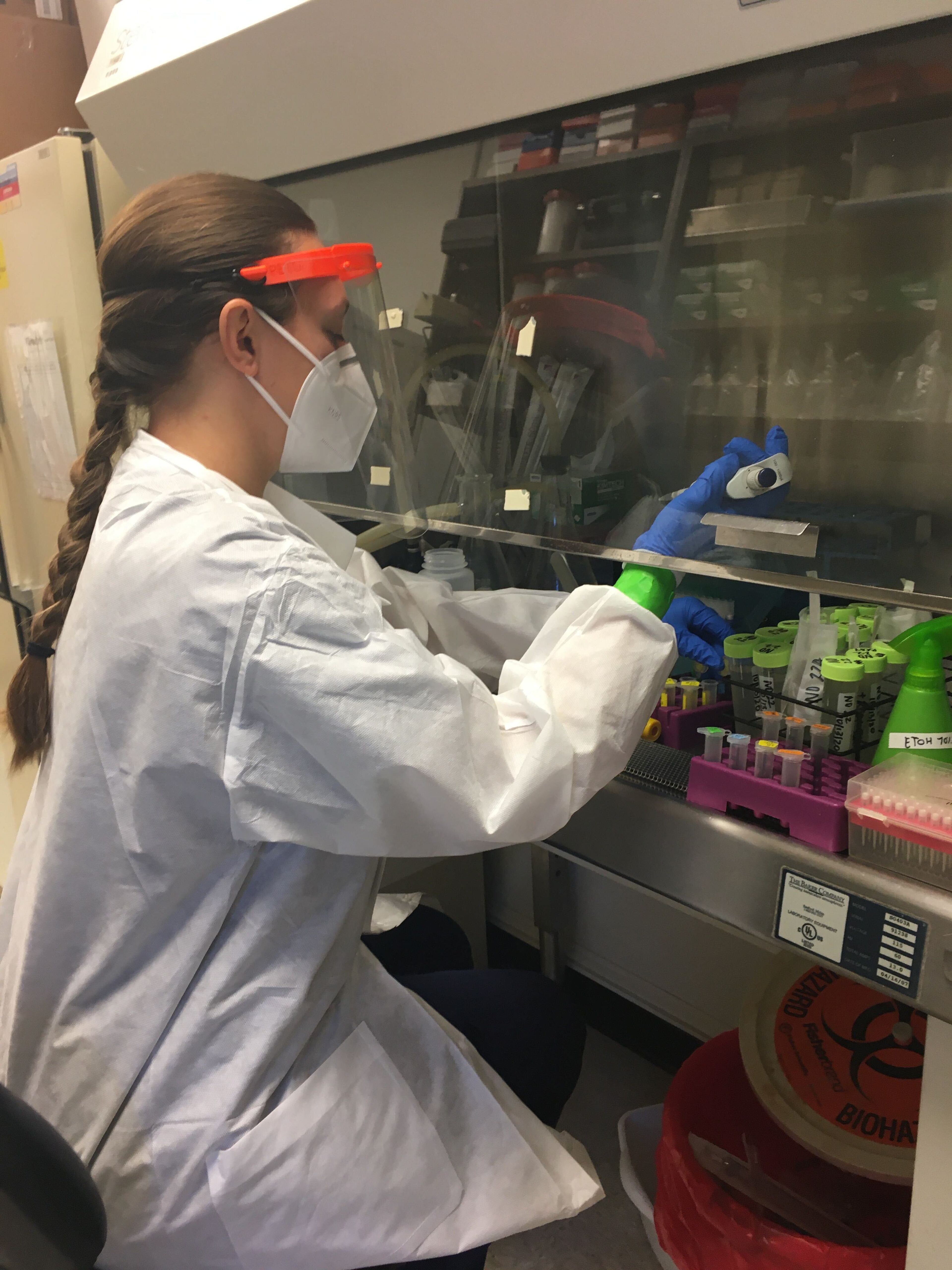

Each week from 6 a.m. Monday to 6 a.m. Tuesday, utility workers in Athens collect samples from two of the largest water treatment plants in Athens-Clarke County. At the University of Georgia’s Environmental Health Science Lab, scientists test the samples for COVID-19. In late October, the data posted online each week brought concerning news — concentrations of the virus had increased. While reported cases in the county remained stable, the upward trend could indicate changes in the release of the virus into the community from asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic infections.

“Normally we publish data all at one time, but one reason we started doing this (weekly posting) is we really thought it would be a service to the community,” said Erin Lipp, the project lead and a professor of environmental health science in UGA’s College of Public Health. “It is a different way of doing science for me."

As COVID-19 persists and with vaccines still under development, local health agencies and universities are looking for ways to augment their tools in identifying and fighting the virus. Wastewater testing is still evolving, but it has offered important insight into the spread of COVID-19 in communities nationwide. As many as 65 colleges, including Emory University have analyzed campus wastewater to help prevent outbreaks, according to a recent analysis by NPR.

The latest generation of sewage epidemiology evolved in the U.S. at the start of the century but was mostly valued for its ability to measure the environmental impact of illicit drugs. Years later, researchers would recognize the potential for using sewage to monitor public health concerns. Not only could scientists track drug use in a community through human waste, they could also track infectious diseases excreted in urine and feces and identify outbreaks several days or weeks before they occur.

Recent studies have shown the virus that causes COVID-19 can be detected in waste within three days of infection, much sooner than the incubation period of up to 14 days for a symptomatic infection to reveal itself.

Biobot, a Boston-based company founded by two researchers from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, quickly shifted from monitoring and analyzing opioid use in communities to rolling out a campaign to test wastewater at water treatment facilities nationwide.

The program, which ran from March through May, included 400 water facilities in 42 states. “We began to see how our data could be a leading indicator,” said Jennings Heussner, business development associate for Biobot. “When we see a spike in viral titer (or viral load) in wastewater, there will be a corresponding spike in clinically reported cases some four to 10 days later,” he said.

Georgia was not among the states that participated in the pilot, but in early September, the White House Coronavirus Task Force suggested the state explore the use of wastewater surveillance for early virus detection and community intervention. Weeks later, after the state reported fewer COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people than the national average, the Task Force moved Georgia from the most severe category for COVID-19 cases. But within the past few weeks, seven-day rolling averages for daily new coronavirus cases have been ticking upward.

Wastewater epidemiologists believe the predictive qualities of wastewater testing can help municipalities get a jump-start on managing outbreaks in the future, particularly as the country continues to reopen. But sewage sampling is very complex, said Lipp.

Wastewater includes not only human waste, but household waste and other materials. It is easier to detect COVID-19 in the wastewater samples when caseloads are high. The test is not as sensitive when cases are lower. While it isn’t possible to quantify the number of cases in a community, it is possible to measure trends. “Everyone would like to take a sewage sample and tell you how many people in the population are affected, but the science is not there yet,” said Lipp.

Scientists are also continuing to research how samples should be collected, specifically if it is sufficient to draw samples from wastewater treatment facilities or if a raw sample, such as from the sewers that feed into treatment plants, should also be part of the sample collection.

There are also questions about the frequency of testing, including how many times per week and how many times per day samples should be gathered. Standardizing these practices would make it easier to create a national database that could help predict where the next outbreak will be, said researchers.

Countries in Europe and Asia already have national programs in place. Some states, including Colorado and Ohio, have implemented wastewater surveillance systems to track COVID-19, but the U.S. has only just begun to build the groundwork for a national tracking system.

As of mid-August, efforts were underway at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to create a national database for state, tribal and local health departments to submit wastewater testing data that could be used to support public health action.

The CDC did not respond to the AJC’s request for an update on the status or scope of the National Wastewater Surveillance System.