Major airlines and their trade associations are pushing hard to overhaul the nation's air traffic control system, urging the Trump administration to take it out of government hands for the first time in nearly 60 years.

They have taken their effort to the White House, meeting last week with President Donald Trump.

His administration has not yet said whether it will back the plan to transfer the system from the Federal Aviation Administration, where it's been since the agency's beginnings in 1958, to a private entity.

In her Senate confirmation hearing last month, Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao was noncommittal.

"Obviously this is an issue of great importance," she told the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation. "This is a huge issue that needs to have national consensus."

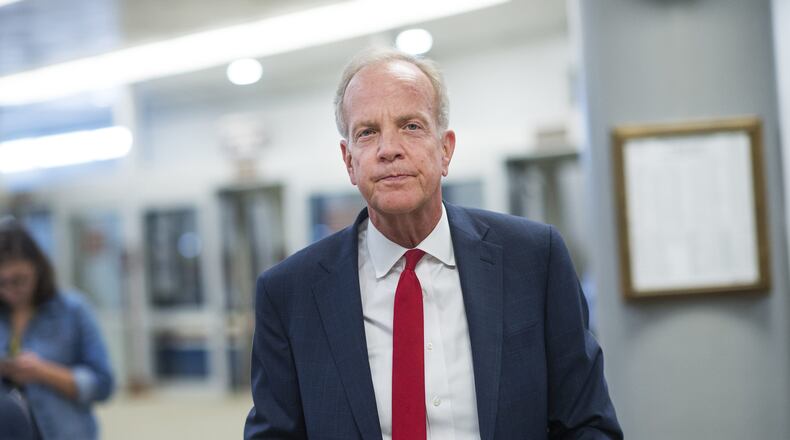

They're facing opposition from Democrats and a few congressional Republicans, including Kansas Republican Sen. Jerry Moran and groups representing general-aviation manufacturers. They said privatization could hurt small airports and companies that make business and personal aircraft. They're concerned that the new board governing the system would raise fees for smaller planes to use the airspace.

The issue could tie up a long-term reauthorization of the FAA, which lawmakers must pass by Sept. 30. The failure of Congress to pass a similar bill in the summer of 2011 nearly brought the country's aviation system to a halt.

"I know that will continue to be a major piece of contention," Moran said in an interview. "It divides the aviation industry."

The industry wants to accelerate the rollout of NextGen, a satellite-based control system that would replace ground-based radar technology. Privatization supporters believe that a nongovernment organization could finish NextGen more quickly and efficiently than the FAA.

Moran, a member of the commerce committee, wants the FAA to use available technology to finish the job. He called the privatization plan "a step further than necessary."

He rejects comparisons to U.S. neighbor Canada, which overhauled its aviation system in 1996.

"Our air traffic control system is considered the best," Moran said, citing its safety record and passenger volume.

Privatization's chief proponent is Rep. Bill Shuster, R-Pa., chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee. It isn't clear where other key Republicans stand on the issue.

Rep. Hal Rogers, R-Ky., former chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, opposed it last year, but his successor in the post, Rep. Rodney Frelinghuysen, R-N.J., hasn't taken a position.

Sen. John Thune, R-S.D., chairman of the Senate commerce committee, set the idea aside last year but in recent months has hinted at a willingness to give it a fresh look.

Nick Calio, the president and CEO of Airlines for America, a trade group representing the largest U.S. carriers, testified in support of the privatization proposal in the House of Representatives last year.

"Delivering a more efficient system with proper governance, funding and accountability will bolster our nation's first-rate safety record and make flying better," Calio told the transportation committee in February 2015, "and at no additional cost to travelers."

Calio, a former congressional liaison for Presidents George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush, pushed the plan in the meeting with Trump last week.

The House committee approved the bill last February, but it never moved to a floor vote.

Congress scrapped the privatization proposal when it approved a 14-month extension of the FAA authorization in July. Lawmakers have yet to reintroduce the privatization plan.

The National Business Aviation Association said in a statement Monday that it could not support any plan to privatize the nation's air traffic control system.

"The U.S. has the world's safest, most complex and most diverse aviation system, and significant progress is being made on implementation of NextGen," it said. "We want to continue that progress, and not have the debate get distracted by a decades-old push by the airlines to take over the nation's aviation system."

Work on NextGen has been going on for about a decade, and last year the FAA estimated that it will cost more than $35 billion to complete by 2030. Critics say the agency moves too slowly and is too beholden to the parochial interests of members of Congress to complete an ambitious project such as NextGen in a cost-effective and timely fashion.

"There's a conflict of interest when you have the same entity operating as overseeing," said Chris Edwards, director of tax policy at the libertarian Cato Institute.

Edwards said these problems could be solved by removing air traffic control from federal hands, as dozens of other countries already have.

"There is a lot of momentum toward this," Edwards said. "There's increasing concern we're falling behind, and we need to do something."

Edwards cited Canada as a successful example of privatization. In 1996, it created a separate entity, Nav Canada, to manage the country's airspace. Though there was concern at first that fees would rise, Edwards said that didn't happen.

"Their fees have fallen pretty dramatically," he said.

Moran, however, remains skeptical that Canada's model would work for U.S. airspace.

"It's a whole different ballgame," he said. "The size and scope are so much greater."

Moran is more concerned that privatization of air traffic control would leave behind smaller airports and general aviation. Kansas is home to numerous general-aviation manufacturers, and small airports dot its landscape.

"It is detrimental in a significant way to rural areas in the country," he said.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured