Two months ago, gas prices climbed to record-setting highs. Now, for 50-plus days, they’ve been inching downward.

In metro Atlanta, prices at the pumps have fallen from an average of $4.55 a gallon in June to $3.73. And, all things equal, the decline will continue, said Patrick De Haan, senior petroleum analyst at GasBuddy, which tracks prices nationally.

The problem is, all things often aren’t equal.

“There are still some wild cards — Russia, the broader U.S. economy and that Category 4 or 5 storm,” said De Haan.

The price of gas, and its contribution to inflation, is among the top concerns of Georgians.

In a recent Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll, it ranked above abortion, taxes and immigration, with 77% of likely voters saying the rising cost of gas and groceries was extremely or very important in determing how they will vote in the fall.

But accurately predicting gas prices is complicated work. Many factors are at play, from the pandemic and weather to international turmoil and oil company decisions on how much to drill.

The ups and downs

Gas prices typically follow a seasonal cycle — higher when summer is approaching, lower when winter’s coming on — and, historically, the swings aren’t drastic. But, over the past several years, that pattern has been upended.

As the pandemic hit in 2020, much of the economy either shut down or went remote. With tens of millions of workers at home, demand for gasoline plummeted — and so did prices. The average price of gas in metro Atlanta fell to $1.60 a gallon, nearly as low as gas had been in the depths of recession in 2009.

The oil industry responded to less demand by pumping less crude and turning less oil into gasoline.

When Americans went back to work and took to the roads again, the industry was slow to ramp up. So, supply struggled to meet demand. That’s the formula for prices to climb, which they steadily did before leveling off last summer.

Then Russia invaded Ukraine in February, and prices soared. Russia provides about 12% of the world’s oil. Though the U.S. gets little of its oil from that country, the change in Russian supplies raised global prices.

Prices here started to drop recently as the vacation season passed, decreasing demand, and as the oil industry’s production continued to rebound.

How prices are set

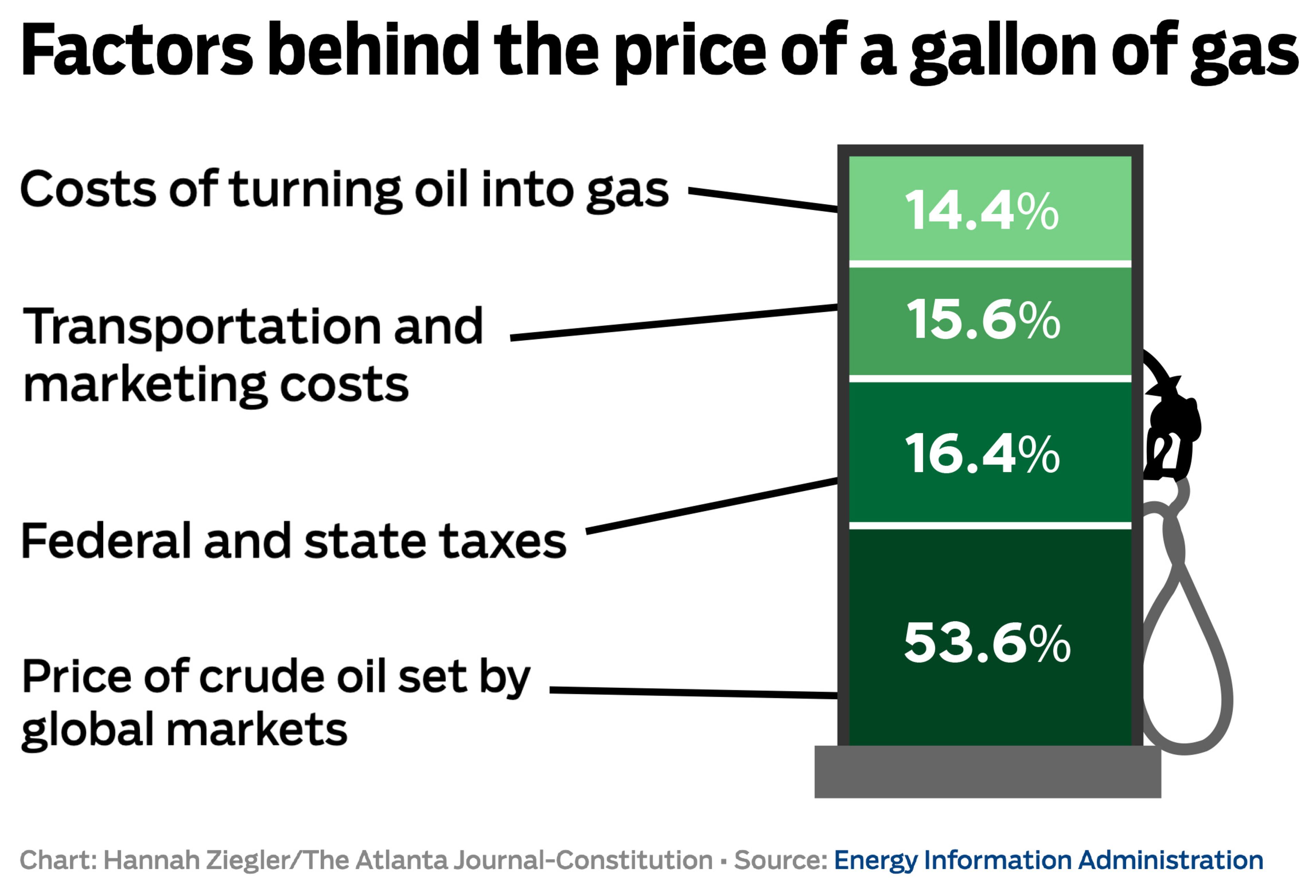

Consumers closely follow gas prices. But the reasons behind their rise and fall are less obvious.

When prices soar, many point their fingers at politicians. However, experts say they deserve little blame when prices go up and little credit when they come down.

Others blame oil companies, which this year reported record profits, but earlier in the pandemic recorded huge losses.

Experts say the big changes at the pump mostly come down to basic economics. For starters, the price of oil, the main ingredient in gasoline, is set in global markets. When oil is plentiful, the price stays low. Fracking, a controversial way to squeeze oil out of shale, has boosted American oil production dramatically in the past 15 years. But when the pandemic started, much of that production ceased and could not be quickly restarted.

When supplies of oil are cut, oil prices increase and gas prices surely follow — the way it did when Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990 or when Russia invaded Ukraine earlier this year.

But that’s not the end of the story, since oil has to be refined. If refineries go down for repairs — or to ride out a hurricane — that means a shortage of gas and a hike in prices.

Controlling cost

Governments can certainly tinker with short-term prices. This year, President Joe Biden ordered millions of barrels of oil released from the nation’s strategic reserve. And Gov. Brian Kemp suspended the state’s gas tax. Both actions lowered prices modestly.

Increasing potential production — for instance, by permitting more drilling on federal land — has no effect for years.

Most of the talk about lowering prices these days is about increasing supply — getting more oil out of the ground or keeping refineries running full-tilt. But, much to the chagrin of those concerned about climate change, there’s little conversation about decreasing demand or lowering speed limits, which conserves fuel use.

Other costs increase with fuel prices

Overall inflation is at a four-decade high. The price of gas isn’t just an example of that, it’s one of the causes.

It’s hard to say how much of inflation is directly tied to high gas prices, but gas prices are connected to many other costs.

Since oil is refined to make gasoline, diesel and jet fuel, the price of oil affects everything that is carried by truck, car and air. That is one reason for the rising price of food. It is also a reason for airline tickets costing more.

But oil prices also affect the cost of electricity, fertilizer, clothes and building materials. Soaring fuel prices also cut into corporate earnings.

It’s a global issue

High gas prices are not just an American problem. Prices at the pump have jumped in many other countries. In much of the developed world, prices have risen as fast or faster than in the United States.

In late July, the average price of a gallon in metro Atlanta was $3.94. In Australia, it was $1.34 a liter — roughly $5.06 a gallon, according to Global Petrol Prices. In England, it was $8.52 a gallon. In Israel, it was $9.12 a gallon.

The countries with the lowest prices tended to be those with economies dominated by oil production, like Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela and Russia.