Ferguson reaction often falls along racial divide

Black Americans tend to believe that what happened to Michael Brown could happen to them. White Americans tend to believe that the decision not to indict Officer Darren Wilson showed the system is working.

St. Louis County officials may have waited until late Monday night to announce that Wilson would not be charged, but many Americans had long since made up their minds. And their views fall largely along the raical divide.

Greg Lange, 31, Chamblee (white): “The officer did what he had to do. In that particular town, they made the officer out to be a cold-blooded killer. But then you learned more — that the kid had robbed a store. It sounds like he was pretty aggressive.”

Blake Jackson, 18, Decatur (black): “Police have been stereotyping young black males for a long time. There’s definitely something racial going on. If he was a white boy, (the officer) would have been indicted.”

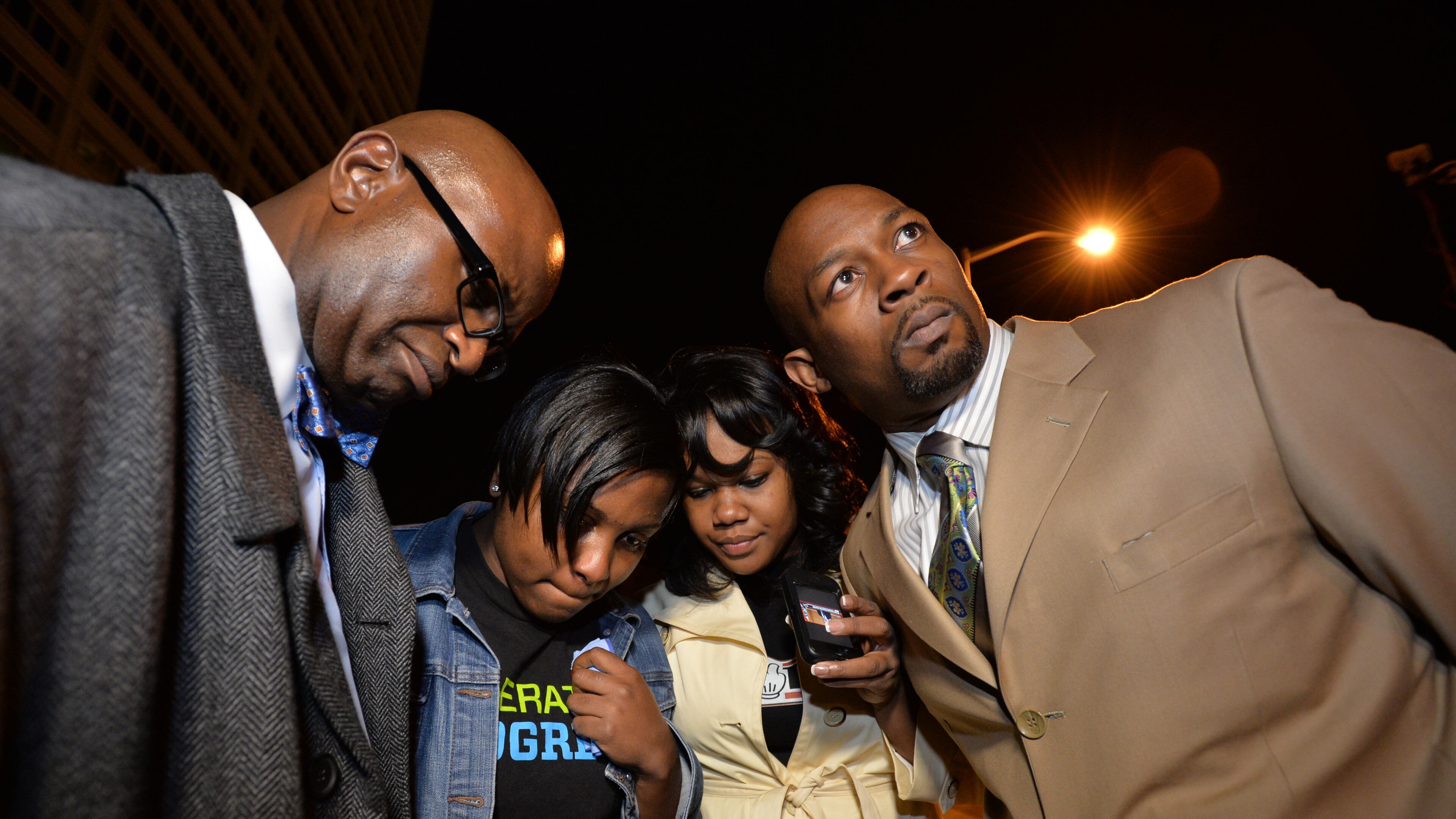

John Evans, head of the DeKalb County chapter of the NAACP, said the decision shows that African-Americans hadn’t come that far from oppression despite the gains from the civil rights movement.

“It’s a disgusting night and some of us aren’t surprised,” Evans said. “They’re still telling us, ‘Hey we don’t want you, we don’t like you, we’re going to kill you.’ “

But some interviewed by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution Monday night said the Brown case was not just a black-white issue.

Les Scott, 53, of Lawrenceville, said the grand jury should have charged the officer, but he did not see the “no-bill” in racial terms. Scott said he suspected, instead, that law enforcement had closed ranks to protect one of its own.

“As a rule, they become a team of brothers,” he said.

Cassidy Hendrix, who is white, said she believed the officer should have been indicted.

“He murdered an unarmed teenager,” said Hendrix, 20, of Powder Springs. “I don’t think people should be able to do that.”

Several people, black and white, were concerned about what would happen in the aftermath of the grand jury’s decision, and indeed Ferguson erupted into police clashed with demonstrators almost immediately. Atlanta, meanwhile, was quiet toward midnight.

“There’s a way to demonstrate, and it’s not rioting,” said Eric Johnson, 26, of Smyrna.

Several political scientists told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution Monday that people would merely plug the decision into their own racial morality play regarding the Aug. 9 incident.

“People on both sides have already constructed a narrative about this, and the judgment is going to be measured against that narrative,” said Robert Grafstein, a University of Georgia political science professor.

In general, it’s easier for white people to see a white police officer as a trustworthy figure, he said.

For many black people, though, this case has become personal, and they were already skeptical about the prospect of finding justice under the law, said Andra Gillespie, associate professor of political science at Emory University.

Several black Atlantans interviewed for this article pointed to race as a factor in the decision, whereas several of the whites said they saw none.

Gillespie, interim chair of African-American studies at Emory, said many blacks will see the no-bill as “reinforcement that justice is different if you’re African-American.”

Jackson, the black Decatur teenager, said he and some friends were harassed by police about a month ago on the Decatur Square. He said they were merely standing together, making no trouble, when the police approached them.

“If it was a bunch of white people there would be no problem,” he said. “But they asked us to leave. They were asking us questions, asking if we had drugs on us.”

Gillespie believes blacks have been more attuned to the case.

“Many blacks take this a little personally. It’s easy for them to imagine themselves in Brown’s shoes,” she said.