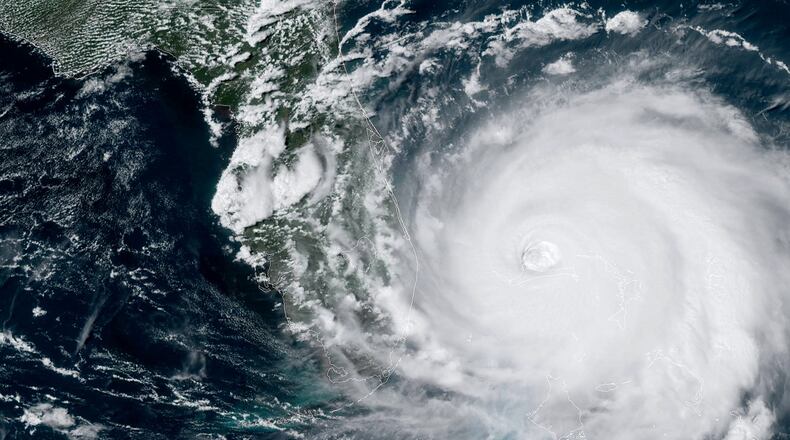

After predicting a “near-normal” hurricane season in May, federal experts revised their forecast Thursday and said they are now expecting an above-average number of storms in 2023, as record-high ocean temperatures create favorable hurricane conditions.

Forecasters at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) project that between 14 and 21 named storms could form this season, with 6 to 11 reaching hurricane status with winds of 74 mph or greater. Of those, 2 to 5 could become major hurricanes

That’s up from the agency’s initial forecast issued in late May, which predicted 12 to 17 named storms, with 5 to 9 growing into hurricanes. Over the past three decades, an “average” season has produced 14.4 named storms, with roughly half of those turning into hurricanes.

The updated forecast comes as the calendar has turned to August and the most active part of hurricane season gets underway. Roughly 90% of storms each year form between the months of August and October, said Matthew Rosencrans, NOAA’s lead hurricane forecaster. Hurricane season officially ends on Nov. 30.

The same factors that drove NOAA’s May prediction — the onset of El Niño conditions and the exceptionally warm sea surface temperatures — are again behind the agency’s new forecast.

El Niño is characterized by warmer-than-normal temperatures in the tropical waters of the Pacific Ocean, and it tends to push strong westerlies across the Caribbean and the Atlantic, which can tamp down hurricane formation. Rosencrans said Thursday, however, that the wind shear typically associated with El Niño has not been as strong as expected, making conditions more favorable for tropical storm development.

Ocean temperatures, meanwhile — the main fuel source for hurricanes — have been breaking records.

Global sea surface temperatures have been abnormally high since April and shattered records in July, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service, the climate monitor for the European Union.

In June and July, sea surface temperatures in the primary hurricane development region of the North Atlantic stretching from the west coast of Africa to Central America were the warmest observed since 1950, Rosencrans said.

“Warm waters are conducive to more development,” he said.

Adding to the risk is climate change, which has tipped the odds in favor of more destructive storms.

With higher global sea levels, storm surge can more easily swamp coastal areas and push farther inland. Warmer air temperatures also mean storms can dump more rain in a short period of time, raising flood risk.

Over the last 120-plus years, Georgia has been fortunate — the state has not had a major hurricane make landfall on its 100-mile coast since the late 1800s. Many storms, however, have raked across the state after striking first elsewhere.

In 2018, Hurricane Michael first came ashore on the Florida Panhandle, before churning north through Georgia, causing billions of dollars in property damage and crop losses.

In 2022, Georgia avoided a direct hit from Hurricane Ian after the massive storm devastated the Florida peninsula. Ian was a high-end Category 4 storm when it made landfall in southwestern Florida, packing winds of 150 mph. The storm was responsible for some 150 deaths and caused approximately $112 billion in damage, making it the costliest storm in Florida’s history and the third-costliest to ever strike the U.S.

Rosencrans urged Americans to prepare now for the storms that may be on the horizon.

“Get your family and your business prepared for the upcoming season, because it really just takes one storm coming through your area,” he said.

Note of disclosure

This coverage is supported by a partnership with 1Earth Fund, the Kendeda Fund and Journalism Funding Partners. You can learn more and support our climate reporting by donating at ajc.com/donate/climate/

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured