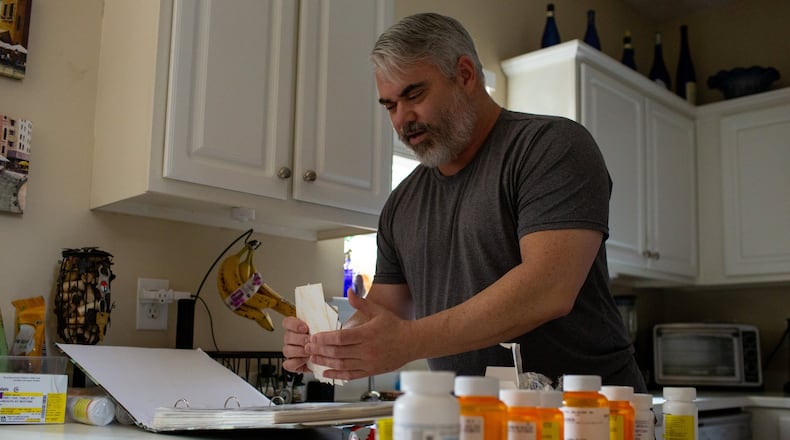

Bruce Barber was hopeful the Department of Veterans Affairs latest $16.5 billion program to send former soldiers to private doctors would speed up access and get him better care.

His experience has been otherwise. He battled for months last year to qualify for the program, which began in June. In mid-December, he was finally given an appointment, 52 days away in mid-February. That’s just for a consultation with a VA neurologist, the first step to qualify for outside help.

“You have to be ready for a fight, because it’s a real battle,” said Barber, a 51-year-old resident of Kennesaw and veteran of Operation Desert Storm.

Last summer's MISSION Act was Congress' third attempt in less than a decade to get veterans into the hands of private doctors when VA facilities can't see them quickly enough, aren't located nearby or don't offer services veterans need. It was pushed by President Donald Trump and is expected to move more veterans into privatized care.

» RELATED: A reckoning at VA Atlanta hospital after years of problems

» MORE: Atlanta hospital suspends routine surgeries amid problems

The VA says the overhaul has gotten off to a good start, authorizing more than 1.5 million visits to outside providers between June and December. The program also allows veterans to visit private walk-in clinics without pre-approval, with 209 of the participating clinics in Georgia alone treating 2,477 veterans during that period.

But in Georgia, at least, there are also warning signs that things have gotten worse, not better. An Atlanta Journal-Constitution review of wait times at metro Atlanta VA health care facilities showed they grew at many locations since the program began, with waits as long as 63 days. And an inspector general audit of a VA district including South Georgia found veterans waited an average of 56 days to receive care last year.

Among the veterans still on hold is Tony Willis, who has worked without luck for more than a year — under a previous program and the MISSION Act — to get an appointment with an outside primary care doctor near him. The resident of Lavonia in North Georgia has conditions ranging from renal problems to collapsed discs and Crohn’s disease.

The last phone call with the VA in early January ended with a promise to get back to him the next day. As of early February, he was still waiting.

“They need to take every one of them politicians and make then enroll in the VA system, and I promise you in six months time the VA will be running like a Timex watch,” said the 52-year-old Desert Shield and Desert Storm veteran.

‘It’s going to be great’; gaping hole in stomach

The VA health care system is ponderous. Its 400,000 employees and 1,255 clinics and hospitals make it the largest health care system in the country. About 9 million veterans, including about 315,000 in Georgia, were enrolled in 2017, according to VA estimates.

Some recent studies have shown the VA provides quality care as good or better than local private hospitals, but the quality rises and falls by locality. Patient trust in VA care is up to 87.8%, the VA reports, but Georgia veterans recorded the lowest patient satisfaction scores last year among the country's 18 treatment regions. The Atlanta VA Medical Center in Decatur, the largest in Georgia, suspended routine surgeries last fall to address problems in operating rooms. It has been restoring capacity slowly.

Congress wrote three increasingly refined bills since 2013 to improve and quicken service by building networks of private practices which could treat veterans.

The MISSION Act eased qualifications. Veterans should be referred to outside care if they can’t see a VA primary care doctor within 20 days or a specialist within 28 days. The same rule applies if they live more than 30 minutes from a VA clinic for primary care or more than an hour from specialty care. Veterans also qualify if the local VA doesn’t offer a service, if the local VA service has been graded below VA standards, or if the VA doctor consulting with the patient decides it’s in the patient’s best interest.

The act farmed out the coordination of care to third-party contractors, who recruit doctors and practices to join, handle paperwork, pay the doctors, and then ship the paperwork to the VA. The VA’s Community Care department also helps with coordination and paperwork.

Trump praised the bipartisan MISSION Act for letting veterans avoid backlogs at VA facilities and see doctors they chose.

“All during the (2016) campaign, I’d go out and say, ‘Why can’t they just go see a doctor instead of standing in line for weeks and weeks and weeks?’” he said after signing the bill. “Now they can go see a doctor. It’s going to be great.”

Since programs to send veterans to private doctors began in 2014, the number of days to get primary care nationally dropped from 24 days to 20. Mental health appointments can now be made immediately. Between 2016 and 2019, VA and private appointments grew by more than 1.5 million each. About one in three veteran visits are now to a private practice and that is expected to increase under the MISSION Act.

But the process for getting an outside referral still starts with an initial consultation with a VA doctor, and that has been a sticking point for Georgia veterans who spoke with the AJC. Once they qualified, they also reported problems getting appointments through contractors.

Appointments disappear along with paperwork. They spend hours on the phone with little result. Referrals to outside doctors from VA staff expire before appointments are made by the contractor.

Larry Donaldson has gone under VA and private scalpels more than a dozen times, the result of his wounding in Vietnam and then decades of surgeries to repair resulting problems. The 73-year-old Acworth resident said he needs another surgery to fix a hole that hasn’t healed in his abdominal wall from a previous surgery.

He said he got VA approvals to go outside the system after June 6, but an outside contractor wasn’t able make the appointment until early December. Three days before the appointment, he said the contractor left a voice message that the scheduled doctor was not in their system, and that he should cancel the visit unless he planned to pay for it or have private insurance pay for it.

He ended up going back to a VA surgeon, and in a January consultation was told the recovery would take more than two months, including two weeks in the hospital. Because he is in the midst of moving to a new home, he has had to delay the surgery again.

“In the meantime, the hole in my stomach continues to grow bigger and bleed more frequently,” Donaldson said.

Wait times grow in metro Atlanta; inspector general finds fault in South Georgia

Metro Atlanta veterans are now waiting longer for appointments at most VA clinics than before the program started, sometimes by weeks, based on an AJC review of publicly available VA data.

Fort McPherson clinic patients waited on average 18 days for an appointment last April. In January, that had grown to 54 days. Waiting times at the Decatur medical center on Clairmont Road grew from 26 days to 45 days in the same period. The Atlanta clinic wait grew from 27 to 46 days; the Hinesville clinic from 28 to 35 days; the North Gwinnett clinic from 11 to 18 days; and the Lawrenceville clinic from 14 to 18 days.

The longest January wait time was 63 days at the Northeast Cobb Clinic, which opened in April.

Two improved: The Austell clinic declined from 42 days to 38; and the Stockbridge clinic fell from 16 days to 4.

In a VA district that includes a slice of South Georgia, Florida and southeast Alabama, veterans waited just under two months to receive care in 2019, according to a VA Office of the Inspector General audit released last month. The audit found the Community Care department was understaffed and that workers were poorly organized and inefficient. At the time of the audit, more than 74,000 veterans had not been scheduled, were still awaiting appointments, or the VA had not completed their paperwork.

The contractor in Georgia that connects veterans and private doctors has been TriWest Healthcare Alliance, which has helped coordinate outside care in previous programs. That will change this month, when a new contractor, Optum, part of United Health Group, will begin taking over. The transition should be complete by May. Optum did not respond to requests for comment.

Howard Sherman, who lives near Helen in North Georgia, tried in July to get a primary care doctor near him and make an appointment with a urologist. A test done at the VA had noted blood in his urine, which could be a sign of dangers such as kidney stones or cancer. He said TriWest tried to refer him as far away as Murphy, North Carolina.

“It was just all messed up,” said the 66-year-old Navy veteran with two active tours on aircraft carriers.

He finally got an appointment with a urologist in late September in Gainesville. After testing, the doctor told him in October that everything looked OK. But Sherman said he is still waiting to find a primary care doctor that will keep him from having to make the hourlong drive to Atlanta.

James Yarbrough in Fairmount, about 60 miles north of Atlanta, is disabled and struggled through 2019 to get multiple appointments with various specialists, including a rheumatologist for his lupus and a dermatologist to check him for skin cancers.

Twice, a VA doctor sent outside referrals to TriWest for a visit to a rheumatologist. Twice, TriWest told him they didn’t get the referrals. Two other times he got sent to doctors for appointments but when he arrived, he was told he had no appointment, according to the 41-year-old Air Force veteran.

Yarbrough said he was still waiting to see a rheumatologist in early January, and that it took months to get to a dermatologist to get a skin cancer removed from his foot late last year.

“It was so bad I had to go out and get regular insurance,” Yarbrough said. “I am dependent upon them for my life, and I really can’t depend on them.”

In an emailed response to questions, TriWest said the average appointment time for Georgia veterans dropped from nine days to seven days since the MISSION Act, and that it received only 147 complaints from veterans in the state for all of 2019.

TriWest said it didn’t make appointments for 7% to 8% of veterans in Georgia in December because veterans didn’t respond to phone calls or mail, or because veterans turned down appointments.

Still waiting

Willis, the Lavonia veteran, said he was still waiting to get a simple appointment with a primary care doctor. The months-long effort has left him and his wife Barbara, who does a lot of VA legwork for the disabled veteran, worn out.

The most recent response from TriWest, according to the couple, was that it needed a referral from the VA to get him an appointment. But the couple said Willis has already received three from a VA doctor, which expired after being unfulfilled by TriWest.

“I should not have to make a 200-mile round trip just to get another referral and have them drop the ball again,” he said.

There are two ways to get care outside the VA system.

1. Simple care: A new program allows veterans who are registered for VA care and who have received VA care in the past 24 months to use a new network of 147 walk-in clinics in metro Atlanta, such as some CVS Pharmacy Minute Clinics, for simple care. You can find out online which clinics participate at https://vaurgentcarelocator.triwest.com/Locator/Care.

2. Complex care: To go outside the VA system in most cases, veterans must be qualified or registered and apply with the VA for approval. To qualify, he or she must meet one of these criteria:

- Live in a state or U.S. territory without a full-service VA facility

- Live more than a 30-minute drive from a VA primary care, mental health or extended care service

- Live more than a 60-minute drive from a VA specialty care service

- Can't get a VA appointment in 20 days for primary, mental and non-institutional extended care

- Can't get a VA appointment in 28 days for specialty care

- Can show it is in his or her best interest to get outside care

- If the quality of needed care in their VA facility for a particular service does not meet VA quality standards

- If the veteran qualified previously under the Choice program by living more than 40 miles from a VA facility, still lives at least that distance away and received care between June 6, 2017, and June 6, 2018

VA doctors meet veterans and can request they receive outside care. VA Community Care departments process the paperwork, and a third-party contractor helps make outside appointments and manage paperwork. The outside care providers must be in-network with the new VA MISSION Act system. You can find those providers on the VA website va.gov/find-locations/. Providers cannot charge a copayment and may not bill the Veteran. The VA may charge a copayment to some veterans, but will send a bill through the normal monthly billing process.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured