The two inmates died three years apart at Hays State Prison from the same easily treatable condition, diabetic ketoacidosis. Neither had been diagnosed with diabetes, raising the specter that signs of the disease had been overlooked.

But if those who make medical decisions in the Georgia state prison system had concerns about the doctor who oversaw the care of Tyrence Mobley and Esteban Mosqueda-Romero, they didn’t act on them.

Less than two years later, that physician, Dr. Monica Hill, got a new job, and it was one with even more responsibility: She was made medical director at the state’s largest facility for women.

Hill’s ascension to the job at Lee Arrendale State Prison, a position she still holds, represents for some another glimpse at how the prison system has failed to make meaningful reforms of healthcare services, even when providers have allegedly mismanaged life-or-death situations.

» RELATED | For some in Georgia prisons, diabetes has meant a death sentence

» FROM 2015 | Women's deaths add to concerns about Georgia prison doctor

Dr. Yvon Nazaire, fired in 2015, was highly regarded by his supervisors until The Atlanta Journal-Constitution published stories about the deaths of female inmates in his care. The state later paid millions to settle lawsuits alleging negligence in his care of inmates. Dr. Chiquita Fye was also held in esteem until nurses and others working for her went public with claims she sometimes withheld critical care because of her disdain for prisoners. She resigned after the state agreed to pay $550,000 to a diabetic inmate whose leg had to be amputated allegedly because of her neglect.

Hill’s promotion after two preventable deaths is “par for the course” for a system that only reacts when it’s under public scrutiny, said Nathan Horsley, the attorney who represented Mosqueda-Romero’s family in a lawsuit the state settled last year for $215,000.

“The level of publicity that’s required for them to take action against medical or corrections personnel is incredibly high,” he said. “The normal response is they either keep that personnel in their positions or perhaps shuffle them around to other prisons.”

Officials with the Georgia Department of Corrections and Georgia Correctional HealthCare, the branch of Augusta University that provides medical services for the GDC, did not respond to interview requests for this story.

The deaths of Mobley and Mosqueda-Romero were among the 12 documented by the AJC in stories last month detailing how diabetic ketoacidosis has claimed lives in Georgia's prisons and jails. Diabetic ketoacidosis, also known as DKA, is only fatal when diabetes is left untreated, and, even when the condition occurs, patients can recover if they are treated with insulin and hydration.

Credit: HANDOUT

Credit: HANDOUT

In Mobley’s case, the 34-year-old from Fairburn had become heavy and bloated in the months before his death, apparently from retaining fluid, according to his mother, Lucinda Bell. “His whole body was big,” she said. “His head was even big.”

The fluid retention could have been a sign of renal failure, a condition often associated with diabetes, but Mobley wasn’t treated for it until he was hospitalized in the hours before his death, his mother said.

Evidence developed by an investigation into Mosqueda-Romero’s death by the GDC and the 2016 lawsuit filed by the inmate’s family raised a multitude of questions.

Most notably, a nurse told GDC investigators that on the day before he died, she brought him to the prison infirmary because his health was deteriorating, but she couldn’t reach Hill, who was out that day. The 63-year-old was eventually transferred to a hospital but only after a physician at another prison facility was contacted.

The nurse, Deborah Jo Wright, testified that the on-call physician wasn’t scheduled until later in the day and that her orders were to call Hill in any case.

But several experts said there was nothing to prevent anyone working in a GDC facility from calling 911 if they believed a prisoner was in a medical crisis.

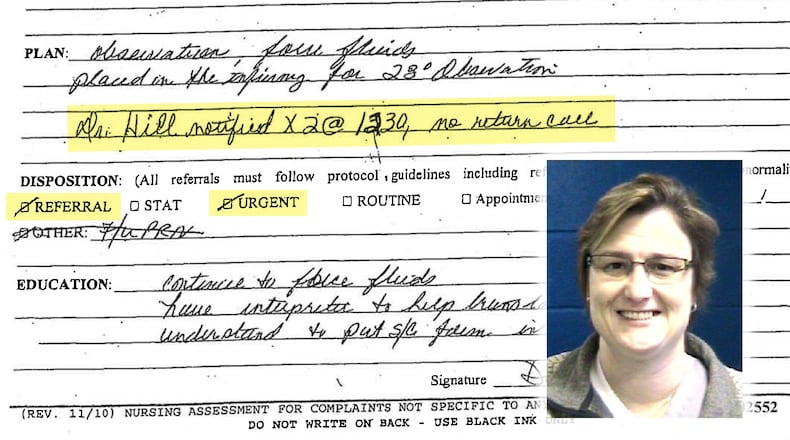

In a court filing, Hill stated that she saw the missed calls early in the evening but didn’t return them because she assumed the caller realized she wasn’t working or on call.

Hill didn’t respond to phone and email messages seeking an interview for this story.

Trouble in North Carolina

Georgia Correctional HealthCare has struggled to hire doctors because of substandard pay. As a result, it has long tolerated issues with physicians that other employers might find disqualifying. A 2014 AJC investigation found that one in five Georgia prison doctors had been hired despite state sanctions for substandard care and other transgressions.

Nazaire was hired as medical director at Pulaski State Prison despite a finding in New York, where he previously practiced, that he had been negligent in his treatment of five emergency room patients.

Hill, a 51-year-old Athens native, was hired in 2009 after she moved back to Georgia from North Carolina, where she had worked as a hospitalist and had come under scrutiny from that state’s medical board.

According to the board, Hill engaged in unprofessional conduct when she attempted to influence a former employer’s decision to withhold pay from a colleague who had failed to report a criminal conviction. The finding was based on a voice mail message Hill left for the chief operating officer of the Cape Fear Valley Health System. In her message, she offered to provide an expert opinion favorable to the hospital “and not point things out” if it would reverse its decision on her colleague, documents show.

The board’s ruling included a one-month suspension, but the suspension was immediately stayed, according to a consent order Hill signed in June 2007.

Documents relating to Hill’s hiring by Georgia Correctional HealthCare indicate that it relied solely on information from the Georgia Composite Medical Board, which made no public finding of its own on the voice mail matter when it licensed her a year after the North Carolina order.

“I don’t find anything negative in her Composite Board file from a credentialing standpoint,” wrote Dr. Edward Bailey, Georgia Correctional HealthCare’s statewide medical director at the time, in an email requesting that Hill’s hiring be approved.

Hill’s starting salary was $150,000 a year. She now makes $170,000. A typical general practitioner makes around $190,000.

Throughout her time working in the prison system, Hill has won regular praise in her performance reviews.

“Delivers outstanding healthcare to offenders utilizing established policies,” wrote Dr. Billy Nichols, Georgia Correctional HealthCare’s current medical director, last June.

Hill has remained on the job despite being cited at least four times for a variety of personal conduct issues, including directing profane and threatening language toward co-workers.

Records show she was in her first assignment as the medical director at Wilcox State Prison only five months when she was cited for using terms such as “dead wood” and “lazy bitch” to describe the facility’s nurses.

After her third such incident in August 2014, she received a two-day suspension without pay and a warning that future episodes would result in termination. But when she was written up again last March after cursing and throwing her ID badge and an attached panic button at Lee Arrendale’s health services administrator, she was allowed to stay on the job.

Christen Engel, Augusta University’s senior vice president of communications, declined to make Nichols available to be interviewed. Responding to a written summary of the information contained in this article, Engel wrote that the university doesn’t comment on personnel matters.

Unexplained weight gain

Six weeks after Hill became medical director at Hays State Prison in January 2011, Mobley was found unresponsive in his single-man cell in the prison’s isolation-segregation unit. Two days later, he was pronounced dead at Redmond Regional Medical Center in Rome.

Bell said her son, who died 10 months after entering the prison system to serve a seven-year sentence for aggravated assault stemming from a shooting in Atlanta, never had weighed more than 180 pounds. But she said she visited him in prison two months before his death and barely recognized him because he looked so heavy.

During the visit, she said, he told her he hadn’t been evaluated by a doctor even though he’d made a request to see one a month earlier.

Bell said she saw her son again at the hospital just hours before his death and noticed that his condition was unchanged. In fact, his wrists were so swollen that the guards contacted the prison to see if they could loosen his handcuffs because they were cutting into his flesh, she said.

Acute renal failure was listed as one of the underlying causes on Mobley’s death certificate.

When Hill was deposed for the lawsuit filed by Mosqueda-Romero’s family, she testified that she had little recollection of Mobley’s death.

“I can’t recall (what happened) without the chart,” she said. “That was shortly after I transferred up there. I had not seen that inmate.”

Asked if there had been any subsequent effort to educate the prison’s medical personnel about diabetes and diabetic ketoacidosis, she said she spoke to a physician assistant, Joshua Cutshall, about “doing a better workup in the future.”

Contacted recently by the AJC, Cutshall, who no longer works in the prison system, said he didn’t recall Mobley’s case.

Credit: HANDOUT

Credit: HANDOUT

A missed diagnosis

Mosqueda-Romero was also in the Hays isolation-segregation unit when he died in January 2014, nine months after he entered the prison system to begin serving a 25-year sentence for child molestation in Hall County.

A blood sugar test when he entered the system was outside the normal range, an indication that he had diabetes, but he never was treated for the disease, according to records from his family’s lawsuit.

In a narrative prepared for the state’s mortality review, Hill acknowledged that she and other physicians should have seen the reading and ordered appropriate follow-up tests.

The records from the lawsuit settled last year also indicate that the inmate exhibited classic signs of DKA, including vomiting and loss of balance, for several days in his cell, yet was only moved to the prison infirmary on the day before his death.

Then, the records show, hours passed before Mosqueda-Romero was transferred to Redmond Regional Medical Center as the primary provider on duty at the prison infirmary that day, a licensed practical nurse, tried unsuccessfully to contact Hill.

The LPN, Wright, testified in a deposition that she was under orders to always contact Hill in the event of a serious issue with an inmate. Records show Wright made two calls to Hill, neither of which was returned.

However, in her deposition, Hill denied that such a directive was in place. The only time she was supposed to be contacted in every instance was when the prison was on lockdown, she testified.

After reviewing the case records for Mosqueda-Romero’s family, the medical director of the Salt Lake County Prison System, Dr. Todd Wilcox, wrote that leaving an LPN to assess an inmate in such a precarious situation was “so far out of the scope of practice that it represents supervisory failure and administrative incompetence in designing this healthcare system and operating it.”

Dr. Yvonne Neau, then serving as the medical director at the privately-operated Wheeler Correctional Facility, provided an expert opinion on Hill’s behalf. Neau said it wasn’t clear whether the calls to Hill were for an inmate’s urgent care. She also noted that it’s “common practice” to defer to a physician on call.

“Call sharing is utilized to decrease a physician’s call burden which can negatively impact care when a physician is fatigued,” Neau wrote.

The cost to taxpayers

While Georgia officials have praised prison doctors for reducing costs, the state has paid out millions of dollars in recent years to settle lawsuits alleging that inmates were deprived of essential healthcare. In the last year alone, the state has paid more than $3 million to compensate inmates or their families, according to records reviewed by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. At the same time, the AJC has documented dozens of cases in which amputations, major surgeries and long hospitalizations have resulted when cancer and other serious inmate health problems were misdiagnosed, inadequately addressed or postponed. Those cases are also part of the burden for taxpayers because they require hundreds of thousands of dollars over what might have been spent had adequate or preventive medicine been practiced in the first place.

The Latest

Featured