Lisa Anderson was raped late one evening in the fall of 2003, while attending graduate school at the University of California, Irvine (UCI).

Her hair had barely grown back after surgery to remove a brain tumor, but for the first time in a long while she was feeling hopeful. She was at a reception for graduate students that night when she met her dissertation advisor and he invited her to dinner to discuss her course schedule.

“I instinctively felt strange about the request, but I chided myself for being so distrustful,” she said. “I tried to convince myself that this was the way graduate students were supposed to interact with their professors.”

Anderson accepted his invitation and got into his car. En route, he told her he needed to stop by his apartment where he invited her in and pressured her to drink a glass of wine.

“When he touched my hair and then my cheek, I knew I was in trouble,” Anderson said.

She tried talking feverishly about her academic work, the brain surgery she’d just undergone, thinking that would turn him off.

“I will never forget the moment that he grabbed my head, turned it toward him and thrust his tongue roughly into my mouth,” she said.

Anderson, a stubborn feminist who once played on the boys’ baseball team in high school and petitioned her school to let women play rugby, froze.

“I cried while I looked at the ceiling,” she said.

She told no one until she learned that her rapist had hurt other women in the past and UCI had done nothing to stop him. About a month later, Anderson finally built up the courage to report him to the university. She just knew that she had to do something so no one else would have to feel the same utter devastation.

Although the school ultimately found that Anderson’s advisor had violated its code of conduct, investigators insisted the rape must have been consensual. Instead of granting her request for a hearing, they quietly suspended him for a couple of quarters. Anderson quickly realized that meant she had to leave. She went to Atlanta’s John Marshall Law School and eventually founded an organization to advocate for sexual assault survivors.

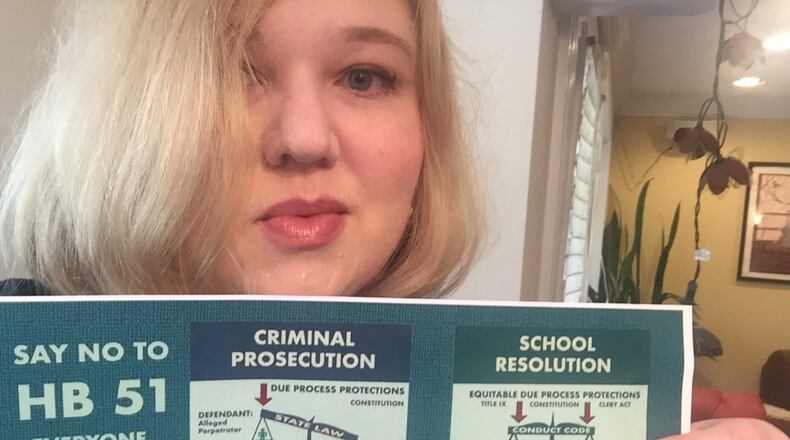

Memories of her assault and the stories she heard every day from her clients at the non-profit fueled her fight against HB51, which sought to change the way post-secondary schools investigate and punish allegations of sexual assault on college campuses.

When it finally came up for a vote a week ago, Anderson, the 39-year-old founder and executive director of Atlanta Women for Equality, a local non-profit that provides free legal assistance to women facing sex discrimination in schools, was sitting in the second row of a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing surrounded by other survivors of sexual assault and their advocates, waiting with bated breath.

For months it looked like they might be fighting a losing battle against HB 51, but now for the first time it hit Anderson that — despite what organizations across the country feared were staggering odds — they might taste victory after all, that legislators across the ideological board seemed as uncomfortable with the proposed legislation as she did. It was far too complex. The stakes were too high.

The bill lays out the due process rights that must be afforded to students accused of sexual misconduct that include bringing an attorney to speak for them during any college administrative hearings and getting the allegations in writing. It says a designated person at each school must report to law enforcement any cases that might qualify as sexual assault, but they are not to identify the victim without permission.

By Anderson’s estimation HB51 would protect accused attackers at the expense of victims. She and other opponents believe victims may be reluctant to report assaults to school administrators because college officials would be mandated to report the allegations to police.

The bill’s sponsor, Rep. Earl Ehrhart, R-Powder Springs, did not respond to a request for comment.

It was close to 8 p.m. March 23 when Sen. Greg Kirk, R-Americus, a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, called to table the controversial bill.

“This is truly a complicated matter,” he said.

Anderson cried tears of relief.

“I was deliriously, happily, hopefully, exhilaratingly exhausted,” she said days later. “I had probably only slept about eight hours total for the week. I hadn’t even let myself dream that the bill would die.”

One reason the stigma associated with domestic abuse has eased in recent times is that victims have become more open about their pain. Many of us now know victims who are friends, family and colleagues.

Rape victims not so much. At many newspapers, including this one, we won’t even print their names.

And so it struck me late last week when HB51 was tabled that the very fact that Anderson and the other women were so willing to stand up, speak out and own their truth is why Ehrhart and the others retreated. Watching the fight play I got the feeling there was a huge disconnect in the way this proposed legislation was drafted and the personal. It's nearly impossible to ignore the personal.

Anderson’s truth was so harrowing it made the hairs on my arms rise up.

Then, just days later, the tabled bill was attached as a rider to another piece of legislation, Senate Bill 71.

Anderson was devastated.

“It’s a very sad day,” she said late Tuesday night. “Heartbreaking for survivors everywhere.”

What she finds particularly saddening, she said, is “the laws we already have provide very strong procedural protections and numerous concrete remedies. We just need to ensure we comply with them.”

Thursday, the last day of the legislative session, was one of the longest in her life and just as trying. One minute she was hopeful and the next all hope was gone.

But shortly after midnight, the gavel fell and the session was over. The bill was dead. Anderson and her supporters cried.

They asked a guard if they could throw confetti. They pulled copies of the bill from their bags, tore it into a thousand pieces, flung them in the air and headed out into the hallway speechless.

“We won!” Anderson said to me in an early morning email. “We’re so happy.”

Friday morning she still was but she was realistic, too.

“I know there are going to be other bills,” she said. “The battle is far from over.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured