After more than 100 years, will Leo Frank be exonerated?

The air in the cemetery felt like wet cotton. The sky rumbled above, but the storms that would down limbs and power lines were still a day away. For now, damp heat and a boiling fury gripped the woman scrubbing the marker placed in memory of the murdered young girl she was named for.

“Sleep, little girl, sleep,” Mary Phagan’s gravestone reads. Her body was discovered in April 1913 in the Atlanta factory where she worked. Factory superintendent Leo Frank was convicted four months after Mary’s death and hanged by a lynch mob in 1915.

A posthumous pardon issued in 1986 didn’t address the matter of guilt or innocence, but a new investigative effort by the Fulton County district attorney’s office means Frank could one day be officially exonerated.

“There’s no statute of limitations on doing the right thing,” said Temple Kol Emeth Rabbi Steven Lebow, who has researched the case for years. “An innocent man was found guilty. Justice is the debt the present owes the future.”

Mary Phagan-Kean is the great-niece and namesake of the factory worker killed at age 13. She is convinced Frank was guilty and livid at the thought of him being declared innocent.

“This issue has already been decided,” she said while she tidied Mary’s resting place.

Her conclusions differ sharply from those of the prominent political and civic leaders behind the exoneration effort. They believe Frank was denied a fair trial and unjustly convicted amid a wave of anti-Semitic fervor that later spurred vigilantes into action.

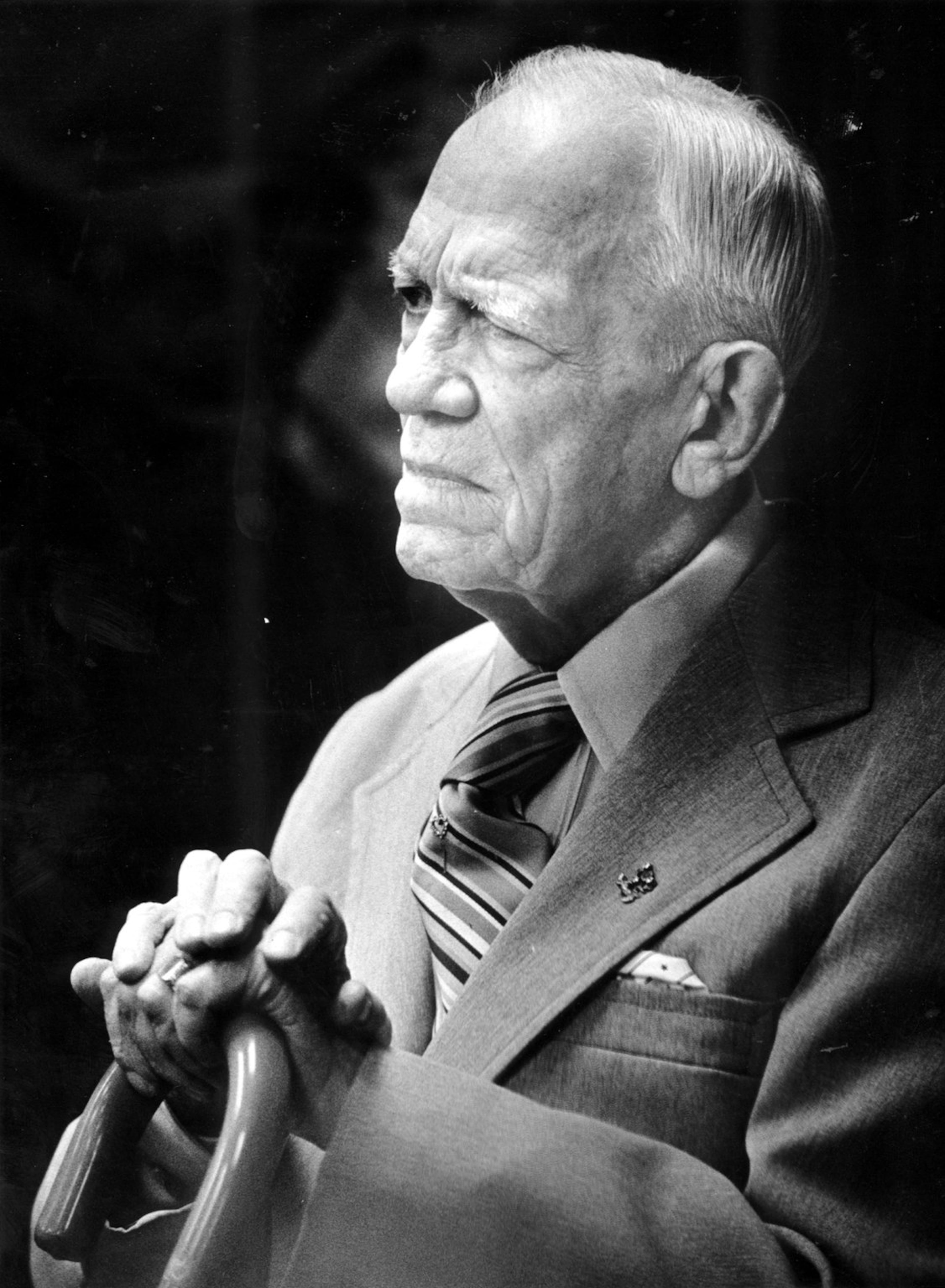

“It is one of the worst wrongs I’ve ever seen,” said former Gov. Roy Barnes.

A longtime legislator before ascending to the state’s top office, he was Gov. Joe Frank Harris’ floor leader when Leo Frank was posthumously pardoned. More recently, Barnes met with Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard to discuss an official exoneration.

“He didn’t get a fair trial,” Barnes said.

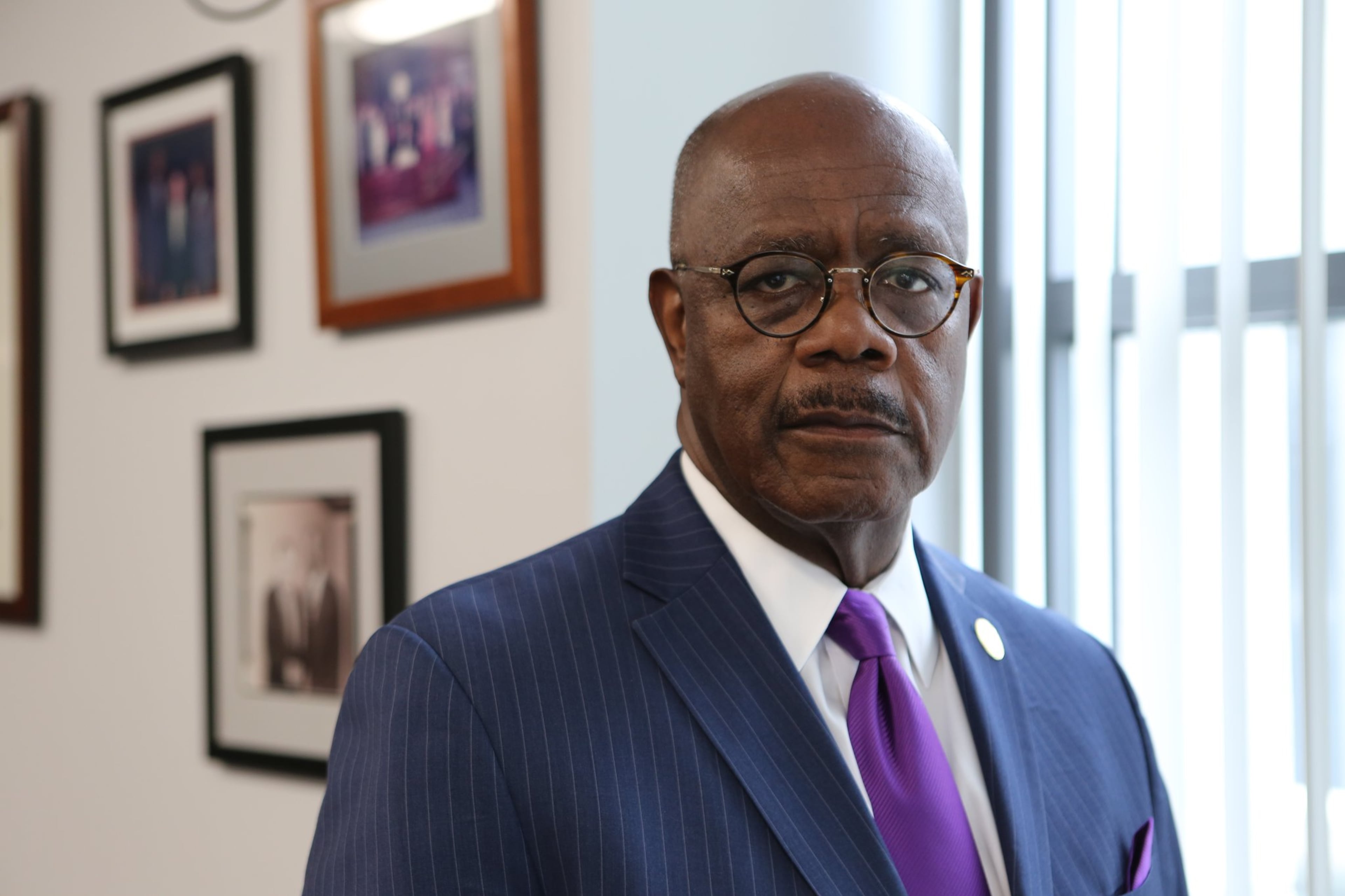

Barnes joined Howard at a May news conference announcing a new Conviction Integrity Unit that will review old cases, including Frank's, and he will serve as a consultant. Aimee Maxwell, former executive director of the Georgia Innocence Project, will serve as the unit's director.

"He never had a chance from the very beginning," Howard said of Frank. "It was so similar to so many African American men who were tried in the South before all-white juries. It seems because he was Jewish they were bound to convict him. When you start to read some of the evidence, you begin to get a clearer picture that if he was convicted, it certainly wasn't based on the evidence."

Frank’s pardon declared that the state failed to protect him and never prosecuted anyone connected to his lynching. In a statement at the time, the State Board of Pardons and Paroles called the action an “effort to heal old wounds” and “put the Leo Frank case behind us.”

It didn’t.

‘Too Horrible to Contemplate’

Mary Phagan was a beauty. Vintage photos show her hair done up in bows, her smile as winsome as a doll’s. She wore a lavender dress her aunt made for her to attend the Confederate Memorial Day parade on April 26, 1913, a Saturday. At about 3:30 a.m. Sunday, her remains were discovered in the National Pencil Company basement. She’d been brutalized and strangled.

“Her dress was hitched up around her knees and a shoe was missing,” author Steve Oney wrote in “And the Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank,” published in 2003. “The belts attaching corset to garters were unfastened and … her underpants had been ripped.”

Police questioned a number of suspects, including factory janitor Jim Conley, before focusing on Frank. He was the last person to acknowledge seeing Mary alive; she had come by the factory to collect her wages. From before he was arrested through his trial and afterward, Frank did himself no favors with his stilted manner. News reports dubbed him “the Silent Man in the Tower,” as he refused to grant press interviews. Images from the trial show him staring blankly ahead, arms and legs crossed.

“Frank was a very bad advocate for himself,” Oney said. “He lived in his head. He was arrogant and he was shy at the same time.”

The case leaned heavily on Conley’s sworn statements. Relaxed and personable as he implicated his former boss, he proved a convincing contrast to the stiff and prickly Frank. Not necessarily to Oney, though.

“When I was working on the book, I was obsessed with how do liars behave,” he said. “I feel like liars are often slick, and truth tellers are more awkward.”

Frank was sentenced to hang, but Gov. John Slaton spared his life. The lengthy commutation order, penned as Slaton was about to leave office, noted his and trial court Judge Leonard S. Roan’s qualms.

“Judge Roan declared orally from the bench that he was not certain of the defendant’s guilt,” wrote Slaton. He also cited a letter from Roan urging commutation, as “the execution of any person, whose guilt has not been satisfactorily proven, is too horrible to contemplate.”

“It is possible that I showed undue deference to the jury in this case, when I allowed the verdict to stand,” Roan’s letter said. “After many months of continued deliberation, I am still uncertain of Frank’s guilt.”

Further bolstering Slaton’s decision was an extraordinary move by Conley’s defense attorney. Convinced his own client was guilty, William Smith also urged Slaton to commute Frank’s sentence. In not issuing a pardon, Slaton respected the jurors’ verdict, but his order reflects anguish over the case.

“I can endure misconstruction, abuse and condemnation, but I cannot stand the constant companionship of an accusing conscience, which would remind me in every thought that I, as a governor of Georgia, failed to do what I thought to be right,” Slaton wrote in the June 21, 1915 decree.

Not quite two months later, a band of self-appointed avengers, many from prominent and well-respected Marietta families, drove to the Milledgeville prison where Frank was held, absconded with him back to Marietta and hanged him. He was married but never had children.

“The minute the commutation order was signed,” Oney said, “Frank was a dead man.”

‘Did He Do It?’

Decades later, former factory office worker Alonzo Mann revealed details he’d never before shared. He said he had seen Conley carrying Phagan’s body the day she died. Mann was 13 at the time. Conley threatened his life if he ever told, Mann said, so he took the secret nearly to his grave.

“I did the last interview with Alonzo Mann,” Oney said. “I’m convinced he was telling the truth.”

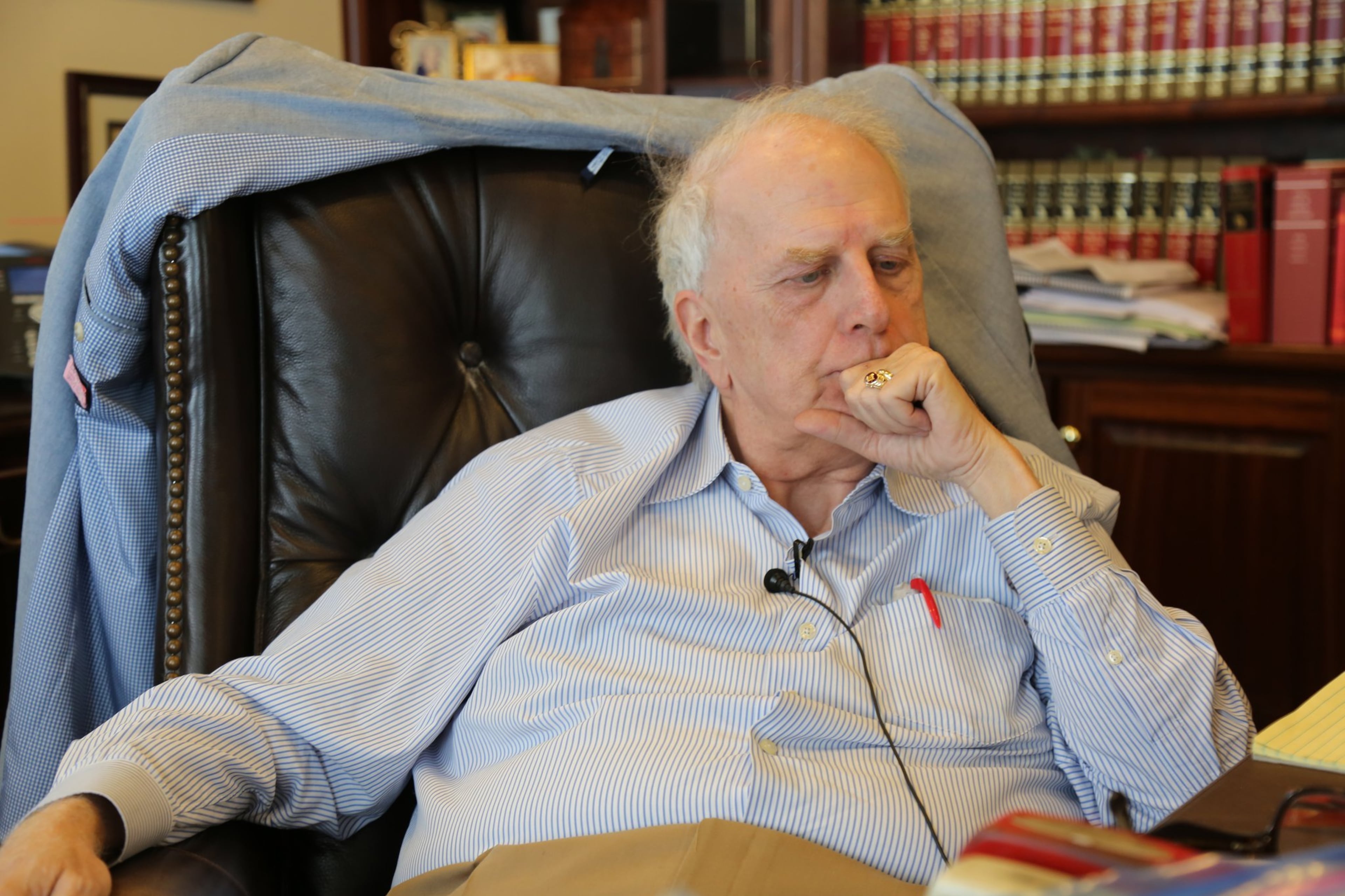

Still, more than a century after the crime, he thinks exoneration will be a steep challenge.

“I think it’s going to be hard for them to find something new,” Oney said. “I’m a little concerned that they have tipped their hand on Frank, that they are looking for evidence to exonerate him rather than just looking for evidence.”

It’s not clear what material might be available to examine. There are no surviving witnesses to interview, the complete trial transcript can’t be located, and there’s no way Phagan’s descendants will consent to having her remains exhumed.

“One of the things we’re going to try to do is find official records,” Howard said. “One of the things I’m interested in is recreating the place where it happened.”

The National Pencil Company on Forsyth Street in downtown Atlanta is long gone. The Sam Nunn Federal Center occupies the land where it once sat. The area where Frank was hanged is now a Waffle House parking lot.

Deputy Attorney General Van Pearlberg, a former Marietta City Council member who has studied and lectured on the case for years, has seen how challenging it will be to locate verifiable evidence. After Frank’s body was taken down, embalmed and sent by train for burial in Brooklyn, curious witnesses claimed grim souvenirs.

“If everyone had a piece of the rope who’s told me they had a piece of the rope, it would drag from here to London,” Pearlberg said.

Still, Howard is determined to press forward. The Conviction Integrity Unit will review available documents and evidence available and make a recommendation.

"The criminal justice system has an obligation to get at the truth," Howard said. "It doesn't matter how long the truth has been undetected."

Oney researched the case for nearly 17 years before publishing his nearly 700-page book.

“Did he do it? I don’t think so,” he said. “But in my book I left the door slightly open. The only three people who were ever going to know were Leo Frank, Mary Phagan and Jim Conley. I guess my sense is in the end, the Mary Phagan murder will remain a mystery.”

A Family Secret

Phagan-Kean was 13 in 1967, more than a half-century after the crime, when she learned who her great-aunt was and what happened to her. A teacher asked if she was related to the young Atlanta murder victim, but she had no idea. Her father told her what he knew about the matter the family never talked about.

“I asked Daddy if I could talk to Grandpa about it,” she said. “That was the worst mistake.”

Her grandfather, William Joshua Phagan Jr., was Mary’s brother. He’d had a stroke and couldn’t communicate well by the time Phagan-Kean brought it up.

“He just broke down and cried,” she said. “I never asked him again.”

A retired educator, she's made a second career out of researching the case. Her book, “The Murder of Little Mary Phagan,” was published in 1987.

"I think Leo Frank killed her and that Jim Conley helped him dispose of the body," said Phagan-Kean, who has amassed a trove of documents and photographs pertaining to the case over the years. "When Alonzo Mann came out, I just felt like he was a nice, elderly gentleman. He verifies, in my opinion, that Leo Frank was guilty."

She also notes that one of Frank’s attorneys had practiced law with Slaton, the governor who commuted his sentence.

“I do believe he was paid,” she said of Slaton. “I just can’t prove it yet.”

Phagan-Kean has a cordial relationship with Pearlberg and has attended some of his lectures, but she has no use for the others involved in the exoneration effort.

“I’m deeply offended by Roy Barnes and the enthusiasts; they have no respect for my family,” she said. As for Frank’s lynching, her late father considered it vigilante justice, but it disturbs her: “I regret the lynching happened. If I could have stopped it I probably would have.”

The case has fascinated Barnes since his law school days.

“You could not have written a Greek tragedy any more poignantly than the story of Leo Frank,” he said. “You had sex, power, money, race and class. It all came together.”

It’s not hard to discern parallels between Barnes and Slaton. Commuting Frank’s sentence ended Slaton’s political career. Barnes was turned out of office after one term following his action to change Georgia’s state flag, which once featured a prominent Confederate emblem. When “flaggers” would launch demonstrations, he’d stop to listen to their complaints.

“The troopers hated it when I did that,” he said. Today, he respects the feelings of Mary Phagan’s descendants.

“What I think should happen is we go through this process, and we make it so clear that there can be no doubt for those with open minds,” Barnes said. “We seem to have lost the idea that we can disagree without hating the other side.”

‘Pillars of the Community’

“The past is never dead,” William Faulkner wrote. “It’s not even past.”

When it comes to the murder of Mary Phagan and the trial and lynching of Leo Frank, the line seems to transcend literature. Everyone involved is long gone, but their ghosts are everywhere.

Barnes’ law office on the Marietta Square is about a half-mile from Phagan’s grave and maybe 2 miles from where Frank was hanged. It looks out onto Glover Park, where stands a statue of Sen. Alexander Stephens Clay. The senator’s son, Eugene Herbert Clay, a past Marietta mayor, was part of the lynching cabal. So was furniture maker Bolan Glover Brumby and his brother, garage owner Jim Brumby.

You pass the Brumby Lofts building on the way from the square to Pearlberg’s house, where his side porch faces Sessions Street. Lawyer and banker Moultrie McKinney Sessions was a member of the ring. The quickest route from the square to Rabbi Lebow’s office at Temple Kol Emeth takes you right by the lynching site. On and on, the past feels ever present.

“There was a time when it was very important to name the lynchers and expose their evil,” Lebow said. “We don’t need to continue to beat Marietta over the head. These were people who never did an evil thing before or after.”

» RELATED: 'Georgia's shame' | Leo Frank's lynching at the hands of an angry mob stunned Georgia and the nation

For Barnes, the paradox turned out to be personal. Barber Cicero Dobbs, the grandfather of Barnes’ wife, was another conspirator. Marie Barnes was a toddler when Dobbs died and doesn’t remember him.

“These people who carried out the lynching were pillars of the community,” Barnes said. “How did they lose their head?”

He expects getting the case ready for the new Fulton County Conviction Integrity Unit will take at least a year. He is hopeful about the outcome, legal and otherwise.

“Human nature can be loving and kind, and it can be mean and terrible. Why do we have to hate? That I have become very concerned with as my hair has become white,” he said. “These were good people who went crazy over hatred and became blinded by prejudice. If we learn that lesson, it is all worth it.”