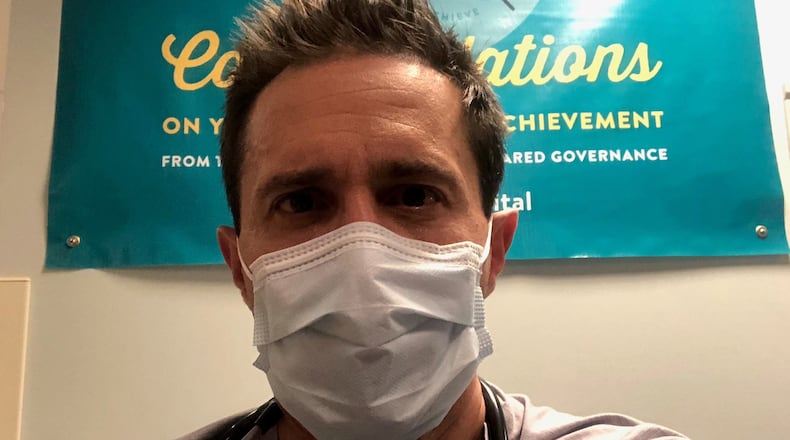

Jason Stein, M.D., works with COVID-19 patients who have been hospitalized in Atlanta, at Emory St. Joseph’s Hospital and in Charleston at Roper Hospital. He graduated from Emory University School of Medicine and has received several awards, for teaching medicine, for practicing medicine, and for patient safety. This interview was edited for length and clarity.

I’m a hospital medicine physician; I live in Atlanta. I work with COVID-19 patients.

We know that we’re not just in our usual roles as doctors and nurses and pharmacists and respiratory therapists. We have to be, as much as we can, the family members of these patients who are dying.

And to the family members who we talk to every day, what I sometimes say to them is, “Look, I know you can’t be here and I know how impossible this situation is. But we are showing as much love as we can to your mother— or your father or your brother or your sister.

“Tell me what you want me to tell them. Tell me something I can say that will make them laugh.”

You know, before the pandemic I never, never would have said something like that to a family member over the phone: ”What can I tell her to make her laugh?”

But if I can do that, help the patient feel that way, share an intimate detail, then I can convey to the patient that I’m talking to the family member. And then I can come back to the family member and I can say, “It cracked her up.”

That’s a beautiful moment. But just—Oh, my God. There’s a cumulative toll that that psychological, emotional burden kind of takes. It wears on nurses in particular.

Changing in the garage

I think the biggest thing that’s changed inside the hospital is, we’ve gone from a state of uncertainty, and anxiety around that uncertainty — How is this virus transmitted? How easily? How safe is the work environment? How unsafe is it, how much occupational risk is there?— to a kind of confidence in what we think we know about this stuff.

When you’re rounding on patients, seeing patients, you’ll take your surgical mask off briefly to put on an N-95 mask. Then you put your surgical mask back on over the N-95. The thinking is that that allows us to wear the N95′s longer, so they’re not single use or single day. You double strap the N-95 to your face. You elastic strap it, double straps in the back behind your head. For it to work, you can’t be able to smell anything.

“We have to be, as much as we can, the family members of these patients who are dying."

There’s people who leave at the end of the day, nurses in particular, and they look like they’ve been sparring. The bridge of their nose is all bent out of shape, the face is all puckered from the super-tight N-95.

I don’t wear a shirt and tie to work anymore. Shirt and tie and a white coat, that’s all gone. Now it’s all scrubs and shoe covers. Leaving work, everybody changes clothes before going home. That’s new. You see people changing clothes in the parking garage. There’s a lot of people leaving, not everybody can stand in the line in the locker room and bathroom, so a lot of people started to change clothes in their car.

Outside of every patient’s room there’s a PPE cart or a caddy. First you sanitize your hands, and then you put on your first layer of latex gloves. And then you pull your gown over you, and tie it behind your neck and behind your back, behind the lower of your back.

And then you take a second set of gloves, and you pull that on over the first set and the sleeves of the gown. And then you put a face shield on. And then you sanitize your gloved hands, and knock and ask for permission to come in and see the patient.

Multiply that activity by 15, 18 times a day.

With repetition you get all this muscle memory and that anxiety goes away. You just get good at it. And you know you’re good at it.

The instances where coworkers have become infected, we’ve been able to understand where it was that they likely became infected, and they were in places or moments where their guard was down. Honestly half of them I think appear to be getting their infections outside the hospital.

We’ve had several of our coworkers infected. They either are out of work for a couple days or they become our patients in the ICU. It’s the same plus an extra level of gut wrench.

“A level of betrayal”

When you see a politician or leader declining to wear a cloth mask, a fabric mask, or complaining it’s too uncomfortable they can’t breathe, my instinct is to ask them to wear an N-95 for 12 hours straight.

There’s just such a level of disregard and betrayal for your front-line worker.

To be asked all the things that America is asking us to do inside the hospital to rescue our fellow citizens—in a sense it’s an easy thing for us to do. Because that’s what we do. What feels like a betrayal is to see those fellow citizens not pulling their own weight.

My mask protects you. Your mask protects me.

Literally I feel safer in a COVID unit, a thousand times safer in a COVID ICU, than I do in the public.

In public, going to the grocery store, the post office, I’ve been mocked, “Oh look at the guy wearing the mask.”

Then to see leaders in serious positions not wearing masks themselves and dismiss the value of social distancing and masking? And making it a zero-sum decision of, “We either open up and be mask-free and just live our lives,” or this false alternative of, we have to huddle inside with a mask and be scared?

It makes me shake with anger.

It’s all entirely manageable.

“To see leaders in serious positions not wearing masks themselves and dismiss the value of social distancing and masking? ... It makes me shake with anger."

We know the contours of how to manage it. What makes me angry is the willful disregard for managing this well. It’s so unnecessary to try to tell a narrative that’s anything other than, “Hey, we can manage this together.”

I think I’ve kind of grown accustomed to the idea that we’re going to continue to mismanage this. And that whatever surge is coming, we’ll manage it inside the hospital. With faith and trust in the front line.

And just sadness and regret, tinged with betrayal, that the numbers are going to be as high as they’re going to be.

This doesn’t have to be that way.

------------------------------

Read more: Throughout the pandemic, Georgia physicians have talked with AJC health reporter Ariel Hart about their experiences. For more insights into what they’ve seen, you can find their stories here:

About the Author

The Latest

Featured