It’s among the more gruesome mass murders in Georgia history, one that raised the ire of a president and spawned multiple investigations by the FBI.

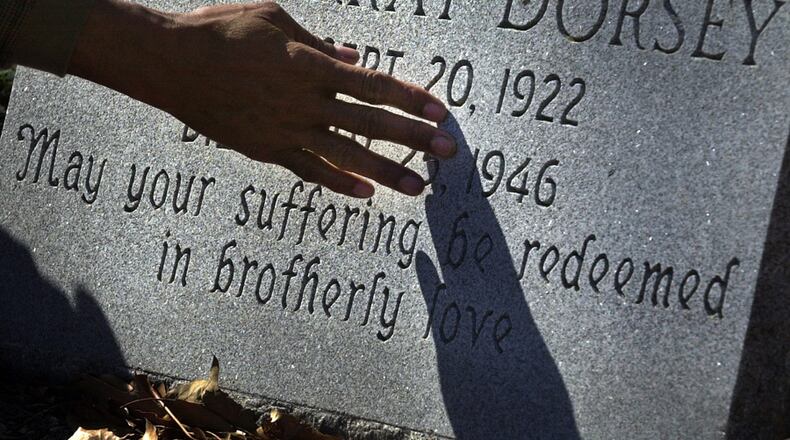

Now, nearly 68 years after two African-American couples were lynched on Moore’s Ford Bridge in Walton County, local civil rights leaders who continue to investigate say they have unearthed credible information that could finally solve the case.

The source is a 55-year-old white Monroe native who claims his late uncle and at least another dozen locals, all members of the Ku Klux Klan, participated in the July 25, 1946 killings of Roger and Dorothy Malcom and George and Mae Murray Dorsey.

“All through my life I’ve heard them talk about it,” Wayne Watkins said. A few years ago, Watkins got in touch with longtime Walton County civil rights activist Robert Howard.

The two men developed a relationship, and Howard said he trusts Watkins.

“He’s been talking a long time, but no one’s been listening,” Howard said of Watkins.

Ed DuBose, former president of the Georgia State Conference of the NAACP, told the Walton Board of Commissioners Tuesday night he wants the commission to push for a special prosecutor based on the new information.

“I’m confident that we’re closer to justice than we’ve ever been before,” said DuBose, representing the Georgia Association of Black Elected Officials.

The sharecroppers were abducted by an angry white mob after a local farmer, Loy Harrison, had bailed Malcom out of the Walton County Jail. He had been accused of stabbing a white farmer days earlier.

The group was on their way home when they were grabbed, taken to a field near Moore’s Field Bridge, tied up and shot more than 60 times. Harrison was unharmed but claimed he could not identify the killers.

Watkins, interviewed on video last April in Monroe by then-NAACP President Ben Jealous, said he knows their identities. Many of them, he said, are still alive.

State Rep. Tyrone Brooks, D-Atlanta, was present during Watkins’ interview with Jealous and said the information he provided “coincided with what we’ve uncovered in our investigation,” though there was one bombshell that came as a shock to everyone familiar with the case.

One of the slaughtered women, according to Watkins, was pregnant at the time. Watkins’ uncle insisted the baby was not killed, however.

“They cut the baby out, washed it in the creek, and took it to Atlanta,” where it was put up for adoption, Watkins said on the video.

The case attracted national headlines when it occurred, prompting President Harry S. Truman to demand the shooters be brought to justice. Up to two dozen suspects were thought to be involved, but no charges were filed.

The FBI re-opened the case, along with more than 100 unsolved murders from the civil rights era, in 2007.

Special Agent James Hosty, who helped capture the “BTK” serial killer responsible for 10 murders in and around Wichita, Kansas from 1974-91, told the Associated Press in 2010 that the Monroe lynchings proved especially difficult to investigate.

Many of the witnesses or possible suspects either lacked a Social Security number or other identifiers that would help investigators determine whether they were still alive to be questioned or possibly prosecuted, Hosty said.

DuBose said no investigators have spoken with either Watkins or the people he says were complicit in the murders. The information was turned over to the U.S. Department of Justice’s civil rights division, which has declined comment.

The GBI, meanwhile, continues to investigate. “The case is still open,” said GBI spokeswoman Sherry Lang.

It’s unclear what, if anything, the Walton commissioners can do. Board chairman Kevin Little said after Tuesday’s presentation that the commission would consult with its attorneys before moving forward.

“The clock is ticking fast,” Brooks said, as many of the suspects named by Watkins who are still living are in their mid-80s or older.

Watkins, meanwhile, has stopped cooperating with DuBose’s group.

“I have no doubt he’s been getting threats on his life,” DuBose said.

Asked by Jealous why he had decided to came forward, Watkins replied that justice was long overdue.

“I’m tired of it … the racism,” he said. “I’m tired of living with the lies.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured