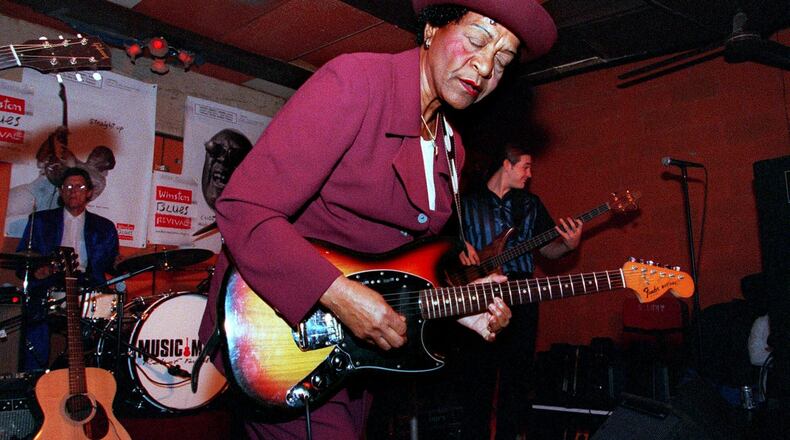

Atlanta blues musician Beverly Hayes Watkins, 80, who performed with James Brown, Ray Charles and Otis Redding, and whose blistering licks on a 1962 red Fender Mustang earned her the well-deserved nickname “Guitar,” died Tuesday morning.

Playing a classic style she called “lowdown blues,” Watkins’ career spanned six decades, during which time she played stages around the world and earned a W.C. Handy Blues Award nomination for her debut solo album, recorded when she was 60.

“She was totally unsung and unheralded and had a worldwide influence,” said Tim Duffy, the founder of North Carolina’s Music Maker Relief Foundation, which supports traditional musicians and music.

She played on seminal rock and blues records that influenced the likes of John Lennon, he said.

Born at Atlanta’s Grady Hospital April 6, 1939, Watkins was three months old when her mother died. Her sharecropping maternal grandparents in Commerce took her in.

Watkins’ life was steeped in music from the beginning, starting with gospel. At home, her maternal grandfather Luke Hayes played banjo, and in a 2017 story in Living Blues magazine, she recalled attending barn dances in her youth when the local farmers would celebrate the harvest with fiddles and washboards and blackberry wine.

When she was 8 or 9 years old, an aunt bought Watkins her first guitar.

“The name of it was Stella, and it had the catgut strings on it. She bought me that guitar on Christmas,” Watkins told Living Blues. “Sometimes my granddaddy would go to a friend’s house and they get together and play the harmonica and jam. I’d be right with my granddaddy with my little guitar and I’d sit up beside him.”

Upon his death, she moved to Atlanta at about 10 years old, living first with one aunt and then another in the Old Fourth Ward.

A preacher named Rev. White would deliver coal to the house, and he would also set up an electric guitar and play, which got her interest.

The first time Watkins performed with an electric guitar was in the talent show at Washington High School when she was about 17.

“He let me borrow his amp and guitar, and I did Blue Suede Shoes,” she told Living Blues.

By a stroke of good luck, overcrowding at Washington forced Watkins to transfer to Samuel Howard Archer High School, where she studied trumpet and guitar with band teacher Clark Terry. He had played with Count Basie and Duke Ellington and was a mentor of musicians such as Quincy Jones and Miles Davis. In high school, Watkins joined a doo-wop band called Billy West Stone and the Downbeat Combo. An acquaintance suggested she contact Piano Red about joining a band he was putting together.

He was another Georgia musician, whose given name was William Lee Perryman, and played barrelhouse style piano. Piano Red and the Meter-Tones played around the state until they had a hit record, “Dr. Feelgood.” With Watkins in tow, the band toured nationally and changed its name to Dr. Feelgood and the Interns, or Dr. Feelgood and the Interns and the Nurse. For the latter iteration, Watkins donned a nurse’s uniform on stage.

“I was young and mens would come up and say, ‘Hmm, I ain’t never seen no woman play like you,’” she told Living Blues. “And I had a lot of them then say, ‘Where did you learn how to play like that?’ and I’d say, ‘Jesus.’”

Watkins toured with Piano Red off and on for decades, and later played with Leroy Redding & the Houserockers and Eddie Tigner, an original member of the Ink Spots. But she also worked washing cars and cleaning houses and offices to pay the bills, Duffy said. It wasn’t until Watkins landed a regular gig busking in Underground Atlanta in the 1980s that she was able to support herself playing music.

Once Fat Matt’s Rib Shack opened in 1990, Watkins began showing up for the Wednesday jam. The musicians in the audience were floored by her fierce guitar work and a popular stunt she would pull, playing guitar behind her head. Among them was blue musician Danny “Mudcat” Dudeck.

“She used to show up — you could see through the glass window when she pulled up — and you would just run up there on stage to get in position,” he said.

About that time, Watkins came to the attention of the Music Maker Relief Foundation. One of its initiatives was organizing blues tours, which frequently featured Watkins. In 1998, she joined Koko Taylor and Rory Block for the Hot Mamas tour, and Watkins, along with Dudeck’s band playing backup, toured Europe on multiple occasions.

With Music Maker producing, she released her “Back in Business,” CD which received a W.C. Handy Award nomination in 2000. It was followed by “The Feelings of Beverly ‘Guitar’ Watkins” in 2004, “Don’t Mess with Miss Watkins” in 2007 and “The Spiritual Expressions of Beverly ‘Guitar’ Watkins” in 2009.

Credit: Jonathan Phillips

Credit: Jonathan Phillips

Watkins was a woman of faith who frequently expressed gratitude for her blessings. In 2006, she and Dudeck were playing the Congressional Blues Festival in Washington, D.C., when Watkins had a heart attack. While receiving treatment in the hospital, it was discovered that she had cancer. Fortunately, doctors caught it early and she beat it.

“She was always thankful for that because that’s how they found the cancer,” said Dudeck. “All these things would knock her down, and she would be thankful.”

Watkins’ musical legacy looms large among blues music fans in Atlanta, especially for women, said Dudeck.

“When Beverly performed, she moved people, but especially young women and girls,” he said. “Guitar playing is seen as a macho kind of thing, so when a woman gets up there and plays, like, amazing,” he paused. “She rocked harder than a man, and that was inspiring.”

Watkins continued to perform well into her later years despite her failing health, including a spot on Steve Harvey’s television show in 2017, and she could be found performing at senior citizens homes and schools. And her skills never wavered, said Dudeck.

“Every single time I ever played with her, especially the last few times, she really surprised me with something I never ever heard her play before,” he said. “She would pull out some amazing jazz stuff. She was always learning.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured